The Real Value of a Portrait

Caroline Morton-Hicks

For me, black and white portraits share an intimate moment. They may be mysterious, but the viewer should be able to connect with the subject on the two-dimensional surface. For that to happen, both the viewer and the photograph must have an emotion. In this way, the portrait has life, meaning and priceless value to loved ones.

But this can be sad, as when I look at the pictures on this page. Both these people are dead; one from old age, the other murdered.

Caroline was an avid musician who played the trombone in local orchestras and bands. I met her several years ago while working on a photographic commission. She let me take photos of her posing with a trombone, a clarinet and a flute. None of it worked. I knew it, she knew it. We took a break. She was raised in England, so we drank tea in her kitchen.

She was a witty person with a sense of humor. I remember her making some wise crack about something, and the New York in me quickly returned the same. That is the moment I made this photo. I gave her small proofs of the “instrument poses,” which she let me know were “horrible.” Nothing I didn’t know. I may have given her a small proof of the above image, but am not sure.

Then, late last year she emailed me out of the blue about adopting a cat. I replied “No thanks.” I like dogs – more emotional. After refusing the cat adoption, I thought I would enlarge this print, mat it and mail it to her. The print was still sitting on my desk when I picked up the paper one morning from the driveway. On the front page was an off-the-cuff smart phone snapshot of Caroline, trombone in hand sitting on a folding metal chair and smiling; she had been shot to death in a desolate parking lot after a band practice one night.

I’m glad I met her and glad I have this photo.

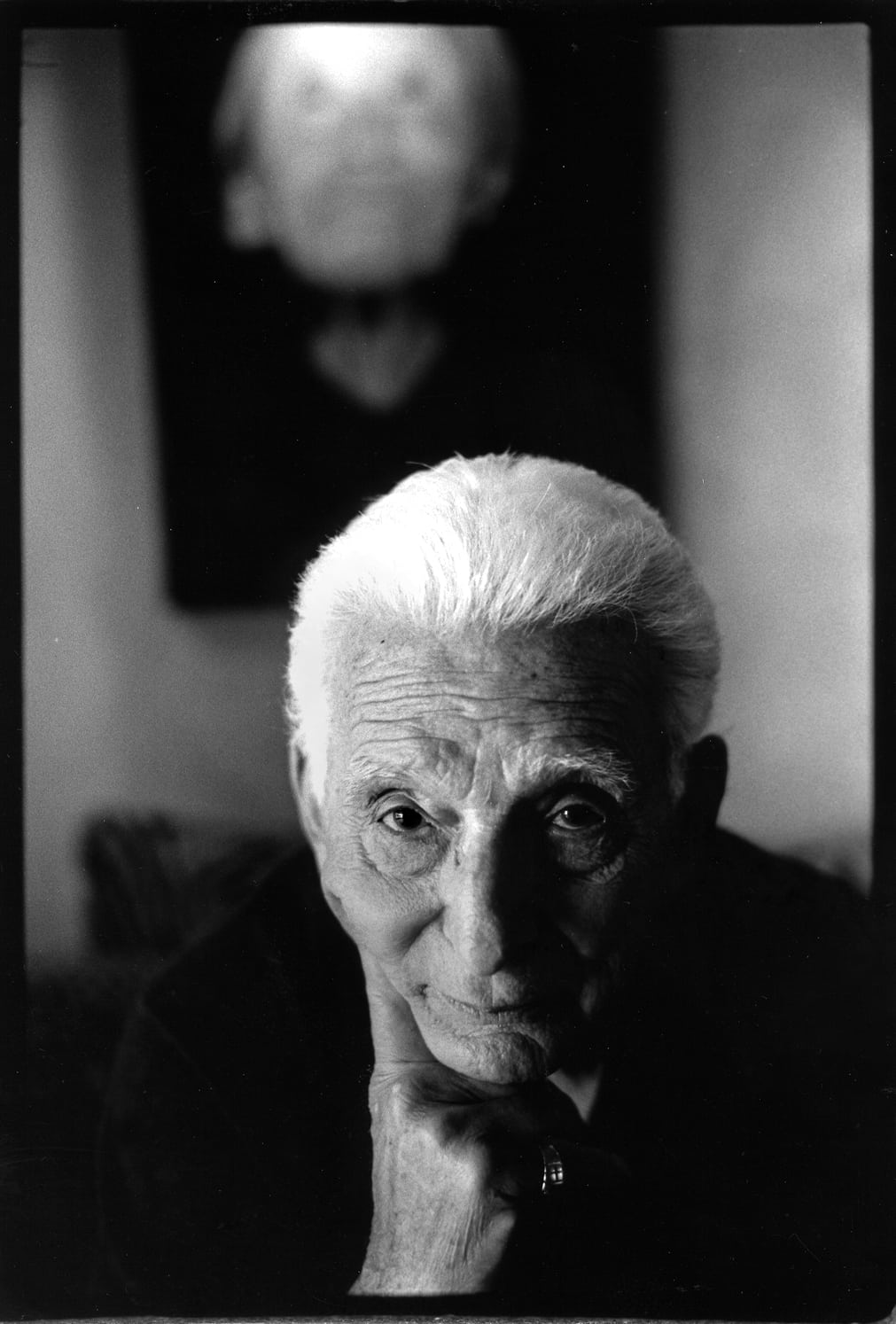

Howard Kanter

Howard Kanter was 88 years old. He lived alone in Tampa. He survived the Battle of the Bulge in WW II. He liked to paint. That lighted painting of an Asian woman behind above him is his work. This photograph was part of a Tampa photographic commission about diversity.

On Veterans’ Day in 2012, the Tampa Bay Times ran it’s usual war hero stories, and Howard’s story of fighting the Nazis along with a photo of him sitting on his porch appeared in the paper. It mentioned he was Jewish. That fit my diversity project parameters. I’m Jewish, so I figured this was one of those times where it might help. (More on that later in my upcoming book about working 20+ years in the construction industry in Pinellas County – The First Jew to make it as a Redneck in the South.)

We agreed to meet in his apartment. There, his daughter and son-in-law made sure I was safe before they left. Howard and I talked. I began shooting. We talked, I shot some more. He seemed incredibly alive. I remember Howard asking me a lot of questions. That made it easier to shoot him. When I make a portrait of someone whom I don’t know, it’s hard to listen and ask questions that prove you are really listening. Sure I’m listening, but I’m making a visual image of what’s radiating from the subject. So if you asked me what questions he asked me and what we talked about, I have no memory there. But I never forget the demeanor of the subject, the way the subject looked into the lens.

What I do remember is this: we were hungry after the shoot, he wanted to take me to his favorite Chinese restaurant, and he insisted that he drive. He had trusted me behind the camera. Now it was my turn to trust him behind the wheel of his vehicle. And he insisted on picking up the tab. His daughter later told me, he had a good time. That made me feel good. It’s too easy to be “taking” from someone when you’re photographing. Photography is like life that way. You need to give to get.

Within a week or two I emailed some thumbnails to Mr. Kanter and his daughter. A few weeks after that, I saw his obituary in the paper. He was in good health, so his death was a shock. “My heart is broken,” his daughter told me over the phone. Howard never saw the enlarged 16- by 20-inch print of this image, nor did his daughter. It’s hanging in the Clearwater YMCA with his obituary from the paper taped to the back.

Death is so permanent. I’ve always been fascinated and frightened by it. When I was about four or five, a relative died. “You mean Uncle Izzy won’t smoke cigars in our house again – ever?” My mother told me, “That’s death. Everybody dies.” I started crying: “I don’t want to die!” She held my head in her lap, trying to comfort me. “Don’t worry, you’re not going to die for a long, long time.”

But the truth was out. I am going to die. At that time, I didn’t have words to express my feelings. Being upset was my child way of saying, “That really sucks.”

Thank God for photos. They can make death more painful, but I’m glad we have them. I think I just “blog-vinced” myself that photos are special and important to me.