By Jennifer Ring

. . .

Saudade Toxosi, DFAC’s inaugural

BIPOC Guest Curator, introduces audiences

to the indigenous concept of ‘we’ in SOONOQO

. . .

Through February 25

Dunedin Fine Art Center

Details here

. . .

What do we become when we work together?

That’s the question at the heart of Saudade Toxosi’s SOONOQO: We become body in waves of light and sound at the Dunedin Fine Arts Center. It’s also at the heart of Toxosi’s curatorial practice in general.

The Dunedin Fine Art Center hosted a Virtual Conversation with Saudade Toxosi earlier this month, where Toxosi spoke with DFAC curators Catherine Bergmann and Nathan Beard about her curatorial process and the artists who worked on SOONOQO. Here’s what I learned about Toxosi via the Virtual Conversation and revisiting SOONOQO afterward.

. . .

Curation by Collective

. . .

Rather than selecting a theme and putting out a call to artists to submit artwork on that theme, Toxosi’s curatorial process begins with the artists.

For SOONOQO, Toxosi selected artists whom she felt “really had a heart for spirit, for nature, for ancestry, for womanhood, and also for what’s next,” she said in her February 9 Virtual Conversation. There are 18 total, including Toxosi. Some of them she met in person through artist residencies, but most she met online.

“I gravitate sometimes online to different people that feel like their expressions in art or their expressions in community, or whatever else, are really of value,” Toxosi shared. “And sometimes they seek me out, but then I have a conversation. That’s really the thing. I initiate a conversation and see how it really flows, and then from that, I have the courage or the vulnerability to ask, ‘Hey, would you like to walk with me through this project or through this idea?’”

. . .

Toxosi selected artists from Africa, Brazil, Copenhagen and all over the U.S. They come in every generation, nationality, race and gender. It’s one of many instances in which Toxosi embraced the collective ‘we’ in this project.

“It’s a convergence,” Toxosi shared in her Virtual Conversation. “We had all these wonderful minds. And we had other meetings besides our initial first meeting of artists. Some of us broke out in groups and spoke about other, different things that were on our minds, or creatively. However, it was very important to me to have voices across generations that were able to talk and to share in one space.”

. . .

A Theme Emerges

. . .

Once she had her artists, they chose a theme together in a series of Zoom conversations.

“I asked everyone,” Toxosi shared, “all 17 because I was viewing us all as one. Nothing separate. We were collaborators. We went through a few rounds of ‘How do we feel?’ What do we see?’ So I had a list that was on Google Drive, and people would add things…”

Multidisciplinary artist Kiara Mohamed Amin proposed the Somalian word Soonoqo.

Jennifer Pyron contributed, “We become body in waves of light and sound.”

“So it was truly dialog and working with all of the artists to bring about the name of the show… and it really encompasses everything and everyone. That’s what I wanted, and that’s how it came.”

It’s a new model of curation — bringing a group of people together to create a communal voice. SOONOQO artist K. Tauches refers to it as the ‘art collective’ model of curation.

This novel approach to curation is part of what drew Bergmann to Toxosi’s work.

“She has such a sensitivity and such a respect for those she works with, and collaborative honoring,” Bergmann says when I ask why they chose Toxosi as their first guest curator. “And we knew that to give her this opportunity would be amazing.”

Toxosi, who is of Seminole and African heritage, is the recipient of the Dunedin Fine Arts Center’s inaugural BIPOC Guest Curatorial Award, which DFAC created to amplify the voices of curators and artists living the BIPOC experience.

“Though we have been mindful and intent that DFAC’s exhibits represent diverse, inclusive perspectives for years now, Nathan and I believe these stories are best told by those who are living them,” states Bergmann, “so we established a bi-annual BIPOC Guest Curator platform to do just that.”

Two years later, the collaboration has come to fruition with Soonoquo: We become body in waves of light and sound.

Their face is flower.

SOONOQO

. . .

The Somalian word is difficult to translate directly into English, a point Toxosi makes in the exhibition’s opening text.

“It considers a pluralistic worldview that allows ‘becoming and returning’ to bear witness of itself, within oneself, while conjoining through space and time,” she writes. “Soonoquo basks itself in the universal soul.”

The idea feels no less abstract when Toxosi attempts to describe it in her Virtual Conversation, “Soonoquo is about becoming and returning, and you cannot become without returning.”

Where words are lacking, art fills in the blanks. The artwork in SOONOQO illuminates the universal soul. It shows us what we can become when we work together, what happens when we return to nature, what we hear when sounds combine, what is created when many different materials come together. The possibilities seem endless.

. . .

In Nature

. . .

Toxosi includes a quote from Cuban writer Lydia Cabrera alongside Spell Casting –

“We are… of the forest because life began there, the saints are born in the forest and our religion [or spirituality] is also born in the forest. Everything is the forest.”

In Toxosi’s Spell Casting, forests, nature, people and art exist as one big video collage. They are dancing, flying, adorning and practicing religious rituals amongst circles and lines — symbols that verify our connection.

For now, through February 25, DFAC’s Gamble Family Gallery is also the forest, seen through the eyes of 18 artists, including Toxosi.

Cara Judea Alhadeff’s self-portraits with a decaying old wooden piano in the forest embrace the circular nature of Soonoqo. Because it is made of wood, the piano becomes the trees in the forest. In Alhadeff’s photographs, we see it return to the forest, morphing back into a pile of wood. Alhadeff joins the piano in the images as if to say that she, like the piano, will one day return to the Earth. This visual togetherness hints at the universal soul Toxosi speaks of.

Three video projections encircle the gallery space, surrounding the viewer with nature. Brandy Eve Allen’s Blood is Life walks us through the many natural environments we find ourselves in. Nayatési Nayatési’s Protection: A Short Talismanic Short Film takes us to the ocean where a man splashes water upon himself in a ritual of sorts, his arms welcoming the water and the Earth. In between, Sall Lam Toro dances with mirror images of hirself (the I is intentional, per hir preferred pronouns).

. . .

. . .

In Sound

. . .

In Chelsea Rowe’s The Fish the Beaches Itself and Thrived video, two abstract forms dance with each other like the lines of a screensaver. The accompanying poem suggests that Rowe’s dancing forms could be bones, flopped up on the beach, in the process of becoming new life.

But I do not see fish or bones in the abstract forms of Rowe’s video. I see notes. One note is only a note, but two or more notes form a melody. They become music, like the music that drifts through the DFAC gallery which hosts SOONOQO.

. . .

In Materials

. . .

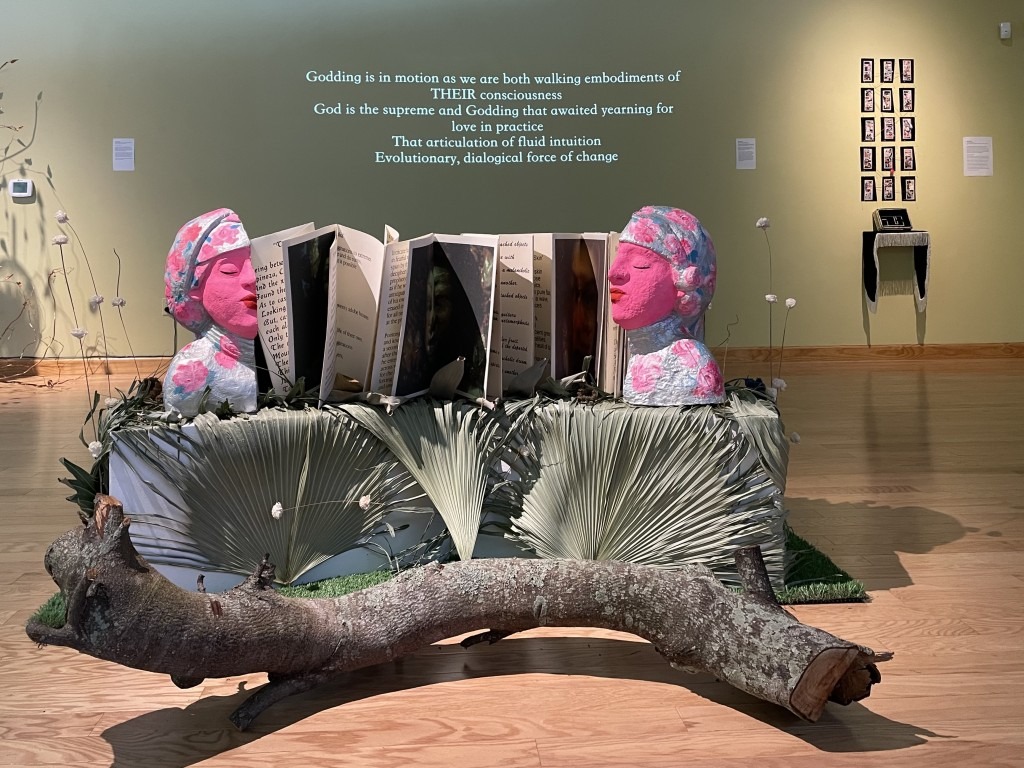

What do different materials become when they work together? SOONOQO artist Micaela Amateau Amato answers this question with flying colors. Her Yoran Por Aire (contes brevas) combines cast paper, book art, text, found branches and leaves with paper flowers, silk cabbage and plastic eucalyptus at the gallery’s center. Toxosi collected and arranged the foliage herself, integrating Amato’s work into a forest of other artists’ creations.

How multiple things and multiple people will come together is one of life’s greatest mysteries, and it’s a mystery that Toxosi cherishes.

“I like to work in the mystery of things,” Toxosi affirmed in her Virtual Conversation. “I feel that the mystery will always find its way. I just have to be patient with it. I have to listen. And I think that one of the things that Nathan and I were speaking of when we were working together, is that – just listening. Listening to one another, but also listening to the space.”

“An exhibition like this, with so many artists, takes a lot of planning, and a lot of thought, and a lot of on-the-ground improv,” Beard chimed in. “Each day Toxosi would bring a new log or a leaf or something in and say, ‘I think maybe this will work. Maybe it won’t.’ Being present and listening was so important to collaborating in the moment rather than trying to enforce some sort of will or vision on the whole thing. It was very adventurous. I remember this week being extremely adventurous.”

. . .

It’s Always We

. . .

The meaning of ‘we’ for Indigenous peoples goes beyond the obvious combination of people and things. Indigenous spirituality, the thread that brings this artwork together, involves returning to the wisdom of the ancestors.

“In the becoming and the returning, we always become through what we’ve learned from our ancestors, and we also return with our ancestors,” Toxosi explains. “So there’s always a teaching, a presence, a knowledge that carries us forward.”

For Toxosi, that wisdom — to have good character, to trust, to listen, and to walk in the unknown — often comes in code.

“Codes of metaphysical, almost sentient, beings like you’d use in divination practice,” says Toxosi. “Ancestors also are represented in nature. They have characteristics. So if you see a bird flying a certain way, or a certain kind of bird, or sun or whatever. Those things are speaking in that time. And it’s about paying attention… That’s about as simple as I can express it, because it’s so nuanced.

“I believe that my grandmother is always with me,” Toxosi continues. “She is never separate from me. She’s always with me, so I can always speak to my grandmother, and she will always answer me. She will show me in a dream, she will show me as I’m driving down the road something that is so nuanced that only she and I will know. It will appear. It will show. So ever-present.”

Ever present, the ancestors grow, heal and learn together with the living.

“As I am growing, they are growing,” Toxosi explains. “They are healing as I am healing. That is the returning and the becoming. All together. Not singular.

“Nothing is ever singular. One of my teachers said to me that it’s always ‘we.’ It’s never ‘I.’ So when I say ‘I,’ she says, ‘No. It’s we,’ because you have to understand – You’re never alone. It’s always we.”

. . .

. . .