Continued…

Glazing techniques led to me becoming incredibly obsessed about the firings and temperatures involved with ceramics as well.

Why do we fire to certain temperatures?

Firing temperatures when using kilns are normally describes in cones, with there being low-fire, mid-range, and high-fire ranges. A high-fire cycle normally describes cones 8-12, mid-range describing cones 4-7, and low-fire generally describing cone 06-01. The cone chart technically starts at the “colder” temperature of 022 and goes up to the “hotter” cone 12.

Cone Chart Barrowed from Ceramic Arts Network:

What happens during a Firing?

I began learning about what happens during a firing once I began firing my own kiln. My first kiln was a small paragon kiln with manual elements- meaning I had to manually increase and decrease the temperatures every few hours by adjusting dials. I soon found a different small automatic kiln. I decided to work with mid-range clays and firings because they were more accessible and they wouldn’t put as much strain on my elements within the kiln.

Honestly, this type of information was the most intriguing to me. Every temperature and hold is done for a reason. It all comes back to the chemistry of the ingredients.

A firing always starts off with a preheating!

The Boiling point of water is 212° F. While firing, if all the physical water in the clay does not evaporate before the temperature gets above the boiling point, the piece could start to steam too quickly and explode from the pressure. So, having a nice preheat where the temperature is held between 180-200° F for an extended amount of time will help the physical water have enough time to evaporate.

Then from around 428° – 1292° F, Plant matter, organic materials with carbon, and chemically combined water begins to burn out.

During this time, from 842° – 1112° F, while the chemically combined water is being burning away, Kaolin begins to transform and Quartz inversion begins. This is when the clay begins to actually be transformed into “ceramic” and it cannot return back to the clay materials state.

The next stage is when full carbonaceous matters and sulfurs begin to burn away as a gas. During the temperatures of 1292° – 1700° F, the kiln has to rise extremely slow to allow those matters to burn away. Some firing schedules that rise quickly through these temperatures can cause pinholes or craters in the finished pieces.

A Bisque firing is normally the first firing the ceramic goes through, and it normally ends between 1872° – 2012° depending on the clay body and the artists’ personal preferences. A bisque firing allows the ceramic body to be porous and accept glazes easier. Everything up to this point describes what normally happens during that process. Once you have added the glaze to the bisqued piece, you cant place it into its second firing- the glaze firing.

The cycle starts pretty similar, with physical water boiling out and chemical water being released from the glaze that was just added to the piece. So firing slowly through those same temperatures as I stated above. Quartz inversion begins at around 1063° F.

From 1400° – 1900° F the frits and soda ash within the glazes begin to melt and the clay body and glaze starts reducing. The glaze is starting to form.

From 1922° upwards (depending on the cone fire top temperature) is when the glaze begins to seal over the ceramic surface and the cristobalite forms.

Once the kiln hits its peak temperature, it begins to cool, allowing the glaze to set in place and no longer be a molten liquid. By the time the kiln is cool enough to open, the ceramic body has shrunk to its final state and you are done!

But WHY?

Learning about the firing process allowed me to correct any problems as I experimented with new clay bodies and glazes. Without knowing what happens during a firing, when you open the kilns at the end, things will always be a mystery.

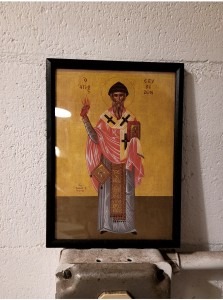

Praying to the Kiln gods can only do us so good!