How did you begin working in sculpture?

For as long as I can remember I’ve been in love with sculpture. When I was 9 years old, my parents took me to see Michelangelo’s “Pieta” at the 1965 New York World’s Fair. As the moving sidewalk passed in front of the polished stone, I saw what looked like living figures frozen in marble and at that moment I knew I wanted to be an artist.

I began working with metal in 1975, while earning a BFA at The Cooper Union. My teachers read like a Who’s Who of contemporary art. I studied with Hans Haacke and Vito Acconci, Kenneth Snelson, Jim Dine and Louise Bourgeois.

Your sculptures are mostly composed of steel and/or found objects. How do you explain this unusual choice of materials?

I have been working with the same types of materials for decades now and I can’t put my finger on exactly why I’m drawn to these objects. What I can say is that I have a deep connection to the act of shaping metals and working with odd assemblages of objects.

When I begin to work with these materials I feel the juices flowing and enter into a kind of creative rapture. The process is beyond logic. I can begin working and something poetic grabs me and changes me and the work begins to exist on its own terms. I am there as a medium to guide the process.

When you graduated from The Cooper Union you began an apprenticeship with Louise Bourgeois. What was it like working for one of the most influential artists of our time?

I was both thrilled and slightly apprehensive when Louise asked me to be her assistant. Always the wry provocateur, she tested my resolve on the first day. Ushering me up a flight of stairs in her Chelsea brownstone, she opened up a closet door and pointed to an inside wall. “You will make a portal”, she said and then walked away. On the floor was a lone pickaxe. When she returned a half-hour later and saw the hole I put in her wall, she smiled and said, “You break through a wall without knowing what is on the other side?”

I made several more portals in the walls of her house over the years. She liked to scurry through these odd shaped archways to escape from exasperated gallery owners and art dealers.

You worked as an illustrator and in broadcast graphics before becoming a sculptor. How did you make the transition from commercial to fine art?

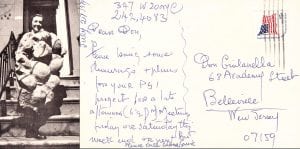

I worked as a newspaper illustrator in Oceanside, CA in the early 80’s. Moving back east in 1983,

I began working at ABC as an artist in the broadcast graphics department. An electronic revolution was underway where pencils and brushes were being replaced by digital art. Specialized computers geared towards artists would fundamentally change the way graphics were created.

I seemed to take naturally to the new tools and as a result, took on greater creative control. Within three years I was heading up the network graphics department. I won an Emmy in 1990. Yet, for all the glamour and challenges that came with the job, I knew I had to make a choice – either grow old as a network executive or leave ABC and work as an independent artist. I chose the latter and never looked back.

You spent some years living and working in Turkey. What was that like?

It was a big change from the bustling halls of ABC to the lone walls of the studio. In the interim, I accepted a position teaching art and design at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey, and moved there in 1992 with my wife and two young sons. Over the next two years I painted and taught.

The European attitude towards artists was very different from what I experienced in the US. Artists were admired as an integral part of society and I felt encouraged. Towards the end of my tenure I had a solo show at Ars Gallery in Ankara, entitled Evrim ve Yokolus (Evolution and Extinction). The success of the exhibition strengthened my resolve to go back to the States and become a full-time artist.

Can you tell us more about the LA Buddha series?

Art critic Dave Quick said it well,

“A recent visit to the Edward Kienholz installation ‘Five Car Stud 1969-1972’ at the Los Angeles County Art Museum (9/4/11-1/15/12) was a powerful reminder that the roots of narrative art utilizing found objects to make impactful social statements run deep. With his current series ‘Bifurcated LA Buddha,’ Donald Gialanella continues the tradition. The nine works are an assemblage of various urban/suburban jetsam and flotsam collected by Gialanella and meticulously crafted into compositions. The over-arching theme of Buddha serves as metaphor for the reincarnation of the objects that lived their initial lives, and are returning in new lives. “The genre is also a nod to Southern California multi-culturalism. (Indeed, one of the area’s largest Buddhist temples is located in the San Fernando Valley not far from Gialanella’s studio.) All nine works are mounted on recycled plastic pallets, which hang on the wall and create space between the wall and the work to create a more three-dimensional, sculptural effect. The pallets themselves continue the metaphorical reincarnation — pallets that once carried other loads, now carry Gialanella’s creativity.

“The artist’s craftsmanship is superb and varied including welding, metal fabrication, incorporation of many different materials and constant attention to the overall composition whereby no single found object dominates its peers. The objects are a wealth of what Southern California is all about – my favorites are fragments of real Cal-Trans freeway signage (what could be more LA!). In total, “Bifurcated Buddha” is a robust creative effort by an accomplished mid-career artist – strong suggestion that

Gialanella has decades of major contributions still ahead.” Dave Quick is co-author of “Motion-Motion Kinetic Art” (Peregrine Smith Publishers), contributes to the Santa Monica Mirror, and in 2011 curated the exhibit “Oceans Four – Mixing Media” for the Annenberg Beach House Gallery of the Santa Monica Cultural Affairs Division.

What was it like living and working in Los Angeles?

I loved living in LA, but having the perspective of being from the East Coast. LA’s a city that thrives on ego and glitz. Show biz, fashion, stars, beaches and traffic – LA is a surreal dream of vapid commercialism and split second fame. Anything goes. It’s a place that allows the artist total freedom where anything is possible.

What artists inspire you?

Jeff Koons, Julian Schnabel, Richard Serra, Hans Hoffman, Cy Twombly, Picasso, Matisse, Giacometti, Dali, Basquiat, Keith Haring and Christo.

How do you stay focused?

I am almost obsessively focused on work. It’s more a question of how to stop working and focus on other things.

What are some hardships in your field of work?

There are both physical and psychological hardships in being a sculptor. Physically, sculpture is taxing work. Lifting, cutting, welding, bending, hammering, grinding, finishing. I face manual labor every time I try to shape unyielding materials to suit my vision.Psychologically, the hardest thing about creating art is having faith that you can will something into existence that hasn’t been seen before and that has meaning to others.

How long does it typically take you to finish a piece?

The process of making a sculpture can be as short as a week or span many months, it depends on the scale and complexity of the piece. Each design goes from that light bulb idea moment to being drawn on paper. Then I make a model or maquette to explore the idea in 3-dimensions. After refining the design a production plan and budget are developed and finally the actual construction of the piece in the studio can begin.

What advice would you give to others who want to become artists?

To be a successful artist requires a singular focus and hard work. You have to devote yourself to making art. People have the idea that artists rush into the studio when they feel the inspiration, but it doesn’t work that way. You have to go to the studio like a job. You are what you do for the majority of the day. If you are working as a waiter to support yourself, it’s impossible to devote yourself completely to the lifestyle of creating art.

You’ve had so many amazing accomplishments and experiences. How does it feel to see one of your pieces in public?

I am very grateful that my work resonates with the public. Communication through visual imagery is the ultimate goal of art. David Salle once said, “Maybe ‘communicate’ isn’t the right word for what an artwork might do; maybe ‘sing’ is better”. The competition is fierce in the public art arena and it’s not easy to be recognized amongst the professional design teams and architectural companies that have become big players. It’s the classic catch-22, most commissions want previous experience doing public work, but the chances of landing that first big public job are very slim.