Guest Editor Babs Reingold’s Roots of Inspiration

Multidisciplinary artist Babs Reingold doesn’t preach but doesn’t shy away from asking big questions about humanity and environmental devastation.

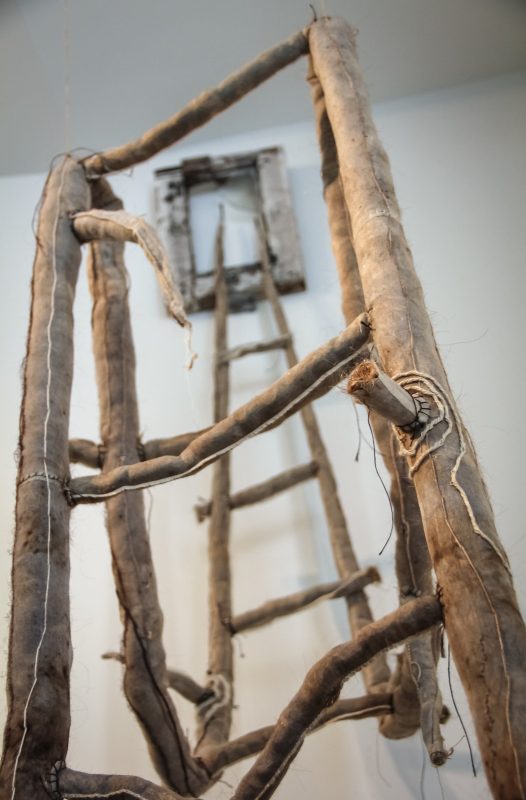

Inside Out –1997-2010 — is a pivotal work in Reingold’s canon and hangs in her foyer. Materials: mixed media: various materials include, paper, canvas, silk organza, wood, rust, tea, charcoal, dry pigment leather pig’s ears, steel, pins and more. – 49in W x 53in H x 4in D. Photo: Daniel Veintiimilla

Viewing her installations, intricate graphite drawings and provocative paintings of female bodybuilders, we’re intrigued and want to learn more about the ideologically eviscerating artist who blurs the lines between beauty and disgust and asks necessary, open-ended questions — like Jared Diamond‘s 2004 invocation: What was the person who cut down the last tree on Easter Island thinking? Or, how can the world’s most powerful nation have one in five children living in poverty?

Big ideas. Important questions. But never overwrought in Reingold’s grasp.

In person, the artist is slender, petite, dressed head-to-toe in black. She wears delicate silver jewelry and stylish spectacles, listens and responds with empathetic tones, and drops F-bombs here and there because she has gleefully detached from the societally imposed constraints of women born in the mid-20th century.

She speaks eloquently about her installations and life events, but expresses volumes with her biographically charged works, using her own hair, photographs and other ephemera referencing her upbringing.

“It’s like how a thumbprint has that sort of uniqueness to it,” she explains. “When you’re an artist, you’re trying to create your unique voice. … After a while, I wanted to make sure that it was unmistakable that the work was from me.”

Reingold with one of the works in her “A Question of Beauty” series, which juxtaposes a childhood photo with snips of her hair collected daily over periods of time. Photo: Daniel Veintimilla

She and her writer husband, James Wightman (yep, another illustrious Babs and James), seem to live a typically liberal arts-idyllic life in a two-story South St. Petersburg home. Natural-but-not-unkempt landscaping by husband; original art by friends; literary novels, books on postmodernism and feminism are shelved amid hardwood furniture, tastefully appointed décor combine in a perfect balance of familial warmth and sophistication. Her 1,200-square-foot studio behind the house, spread over two floors, is just that, working space.

Visiting the Reingold/Wightman home, I could all but picture the couple on Sunday morning working on The New York Times crossword puzzle together as their adorable new Affenpinscher Jake nibbles on a chew toy by the hydrangeas — a notion that would probably make Reingold laugh out loud.

“Jim says my epitaph will be the word ‘more’ she says, poking fun at herself

for her addiction for more workspace. The couple downsized from two

properties (one in New Jersey) into one residence, and though her stuff

appears fairly organized, Reingold lightheartedly laments the crowdedness of

her studio (which has overflowed into multiple outdoor sheds adjacent the

studio) — everything from massive real tree branches to pretend ones to

swaths of cheesecloth to drawings, tins, wire, sculpture and all sorts of

flotsam and jetsam.

Her works convey messier and more deeply conflicted human conditions juxtaposed with chillingly beautiful, harmonious patterns — like an artistic Upside-Down of sorts. The massive installation “The Last Tree (2010-13),” debuted at the ISE Cultural Foundation Gallery in New York City in 2013 and features a formation of 193 hair-stuffed, silk-organza-sewn tree stumps in galvanized-steel buckets; the stark uniformity resembles a cemetery of unknown soldiers. Reingold painstakingly adds atmospheric elements to impart a hollow feeling in the viewer. The number of trees in buckets signifies the countries represented in the United Nations. One large tree rises from the grid, as a symbol of the “last tree” which is in danger of its extinction from the earth. Video, music and audio of Diamond’s aforementioned speech on Easter Island round out the experience.

“Constructing installations verifies existence, validating “the ‘who’ of whom I am.”

A work in progress from Reingold’s “Hair Nest” series. Photo by Daniel Veintimilla

Rust-stained fabric that recalls soiled or blood-stained long johns and underwear languish on a clothesline in “Hung Out in the Projects,” which the Morean Arts Center installed in 2010. A maze of scaffolding conjures fire escapes. The urban sounds of horns and sirens fill the background as words and imagery revolving around poverty in the U.S. project on the wall.

Reingold’s input — the repetition, the frenzy, the months of labor, the uniquely personal and multifaceted symbolism — become a vital, performative part of her output. “Constructing installations verifies existence,” she says, “validating “the ‘who’ of whom I am.”

Reingold had two major influences. Her father, a photographer, was in the industrial sewing machine business with his brother and an Italian war-buddy partner in South America. He parted with his partners after a disagreement and after a move to Texas, was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis. Reingold went from a carefree childhood in sun-drenched locales of Caracas (where she was born) and Barbados to Dallas to living in dismal public housing in Cleveland. Her second influence, a high school art teacher (“the other Jew” at her school) encouraged her to pursue formal art training. She graduated with a BFA degree from the Cleveland Institute of Art, and received her MFA from the University at Buffalo at The State University of New York.

Reingold has an extensive showing history and is included in multiple museum and private collections. Recent exhibits include the “Skyway: A Contemporary Collaboration.” “The Last Tree” also had a six-month run at Buffalo’s Burchfield Penney Art Center.

A photo of her when she was around 2 years old, taken by her father, provides a poignant and beautiful backdrop to her hair-strand diaries and “Hair Nest,” which started when she realized she was losing hair due to a thyroid disorder. “It’s a comment on my own mortality,” she shared.

In her artist statement, she said, “I’ve been complimented on my hair all my life, setting a synergy in place between it and beauty. Once hair loss began, self-doubt was close behind. The hoarding of this loss on a daily basis became a chronicle. As I fashioned each day’s loss into a doddle, a personal calligraphy evolved. This granted my loss an entirely different existence. What was once troubling was now a message on the contextual relationship of beauty. My hair was enduring, aesthetic and flexible. In it’s latest incarnation it is a nest.”

Detail of one of Reingold’s “Luna Window” works (“Luna Window No. 14” 2016). Photo: Daniel Veintimilla

In 2009, Reingold made a jarring discovery: The projects she lived in during her childhood were built on the site of a former Luna Park amusement attraction.

The artist at David&Schweitzer Contemporary gallery, February 2018, with “The Last Tree: Squared.” (2015-2017)