Story and Photos by Margo Hammond

. . .

Hopper and Pène du Bois

Fame in a Fickle Art World

. . .

Through March 26

Free

Polk Museum of Art

Details here

. . .

Edward Hopper and Guy Pène du Bois. Two American artists.

Both born in New York State. Both studied under the same mentors at the same art school in New York City. Both spent time in Paris as young artists. Both evoked a sense of solitude in their work. Both were committed Realist painters. Both were very well known in their day.

Yet now the name of only one of them is instantly recognizable while the other is virtually unknown. Why do some artists stand the test of time while others fall into obscurity? What determines an artist’s continuing fame?

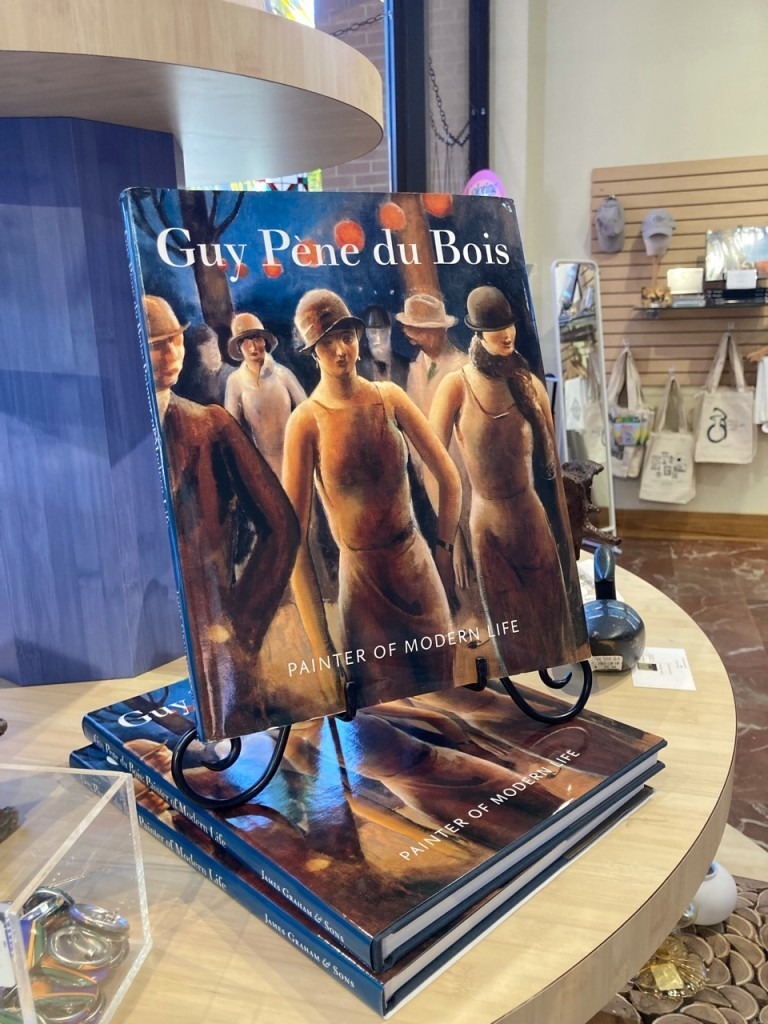

The Polk Museum of Art at Florida Southern College in Lakeland tries to answer that question in its current exhibit — Edward Hopper & Guy Pène du Bois: Painting the Real — which presents works by these two lifelong friends who came to fame together in the 1920s.

Edward and Guy were born 40 miles apart in New York State — Hopper in Nyack in 1882 and Pène du Bois in Brooklyn two years later — but they grew up in very different households.

For the first decade of his life, Pène du Bois spoke only French — even though both of his parents were American. His father, from New Orleans, was an art critic who exposed his son to European art and culture, bringing him to Paris after he graduated in 1905. Later Guy returned to live in France with his family for six years where he captured the life of American expatriates in Paris. He returned home when World War II broke out.

Hopper, the son of strict Baptists, saw to his own art eduction. He took a correspondence course in illustration and, perhaps inspired by his French-speaking friend, also spent some in Paris as a young artist. For most of his mature life, however he lived in Greenwich Village where he had his studio, traveling often to New England where he painted his best known landscapes.

a people-less “portrait” of a house

The two met at the turn of the century at the New York School of Art where they trained with William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri, the art superstars of the day. By the 1920s and well into the 1950s, both Edward Hopper and Guy Pène du Bois were household names in the art world.

Hopper’s career was rocky at first. In 1913 he sold only one painting at the Armory Show in New York. At 38 he finally had his first solo exhibition at the Whitney Studio Club — thanks to the well-connected Pène du Bois. Although younger, Pène du Bois at 34 had already had his first solo show there two years earlier. He introduced Hopper to the studio’s patron, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney.

The Polk exhibit, which includes more than 60 pieces, provides a unique opportunity to compare works by these two artists – who have never been exhibited together before.

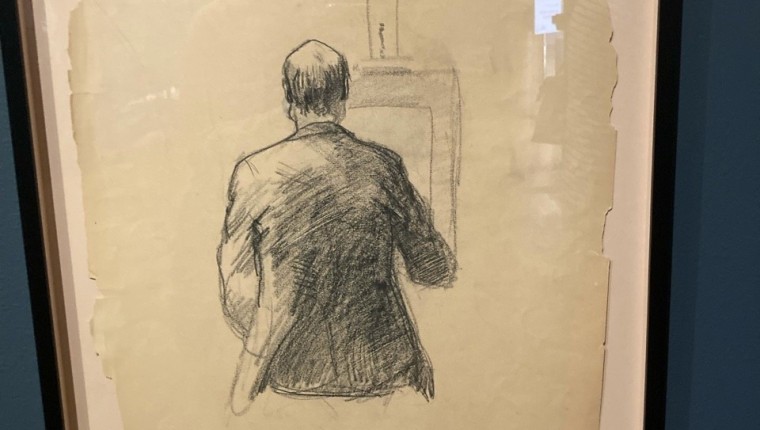

by Edward Hopper in art school

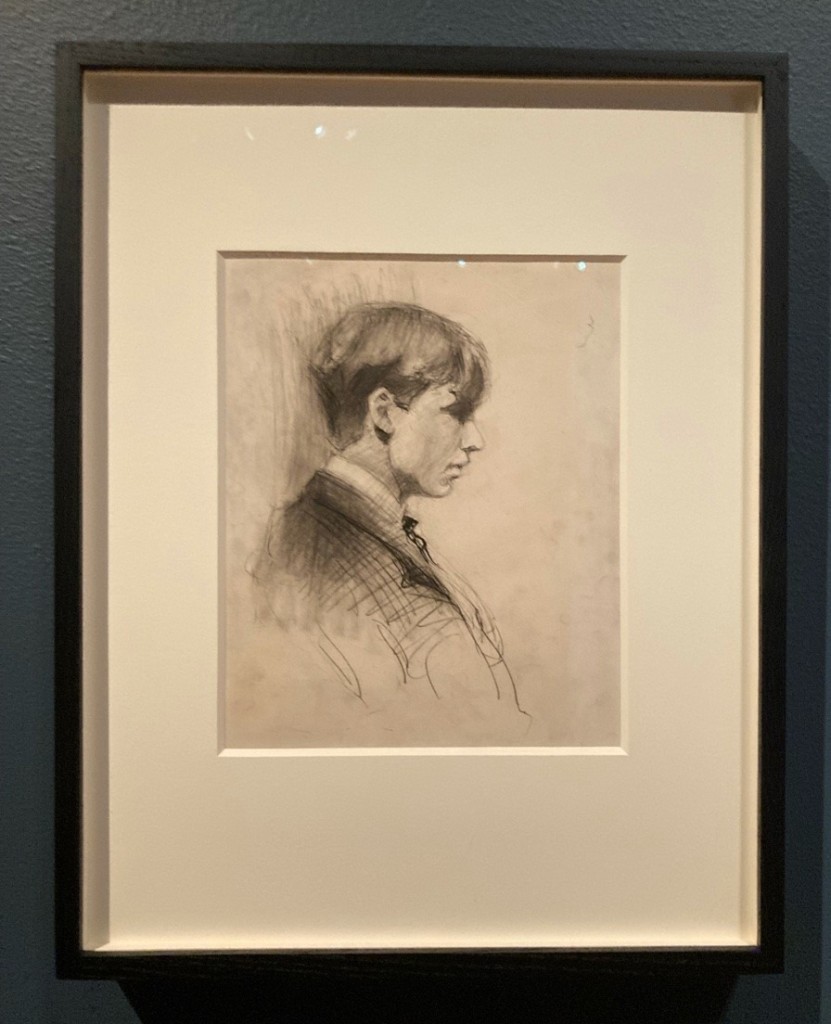

Like many artists, both drew a number of self-portraits. One of six Hopper sketched while still in art school is included in the Polk show. The charcoal drawing shows the notoriously introspective artist in profile, looking away from our eyes.

By contrast, Pène du Bois in his Self-Portrait, a colorful oil from the ’20s, poses at an easel, looking directly at us.

In two other paintings, Pène du Bois inserts his own image in painterly settings – a cafe in Pierrot Tired and a landscape in War Thoughts where in the foreground his head lays next to the death mask of his wife Floy.

death mask of his wife Floy.

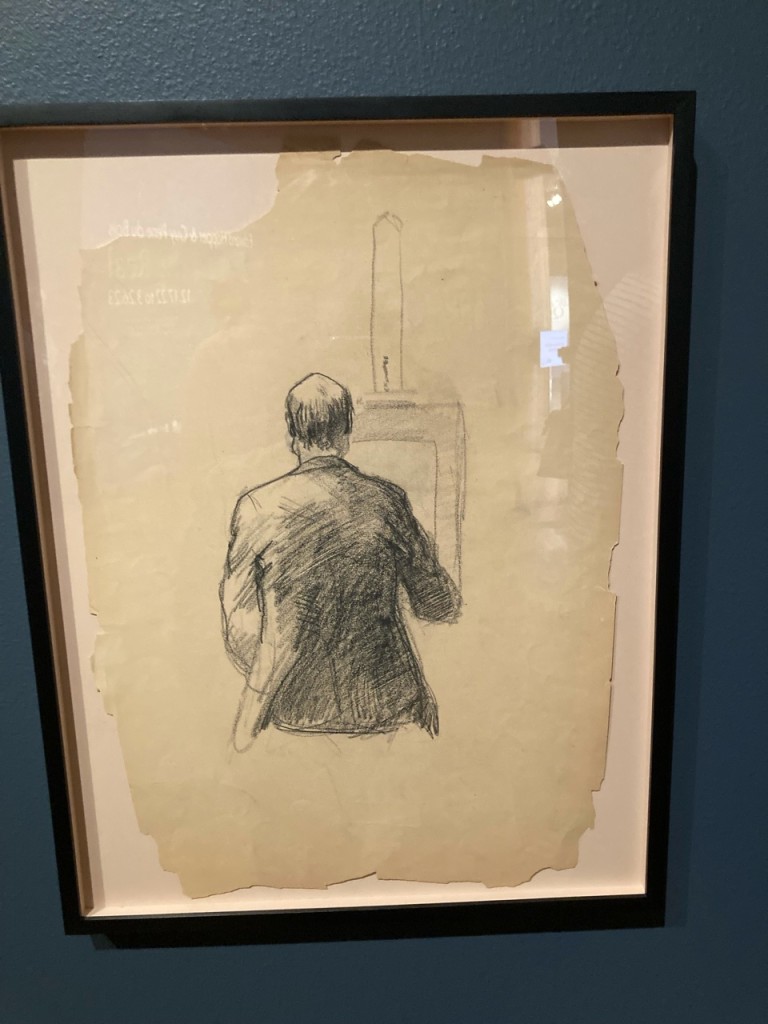

The two friends sketched each other – Pène Du Bois, Our Best Man, a charcoal by Hopper, touts Pène du Bois’ role as Hopper’s best man at his wedding and Hopper at the Easel, a sketch of Hopper from behind, is Pène Du Bois’ playful nod to his friend’s characteristic inward gaze.

A number of paintings by the two artists are “portraits” without people – “portraits” of boats, houses and bridges by Hopper and “portraits” of a deserted garden and a hurricane tree by Pène du Bois. The latter — Road Under the Hurricane Tree — was painted by Pène du Bois after the devastating 1942 hurricane that hit New England where his family lived.

a people-less “portrait” of a tree

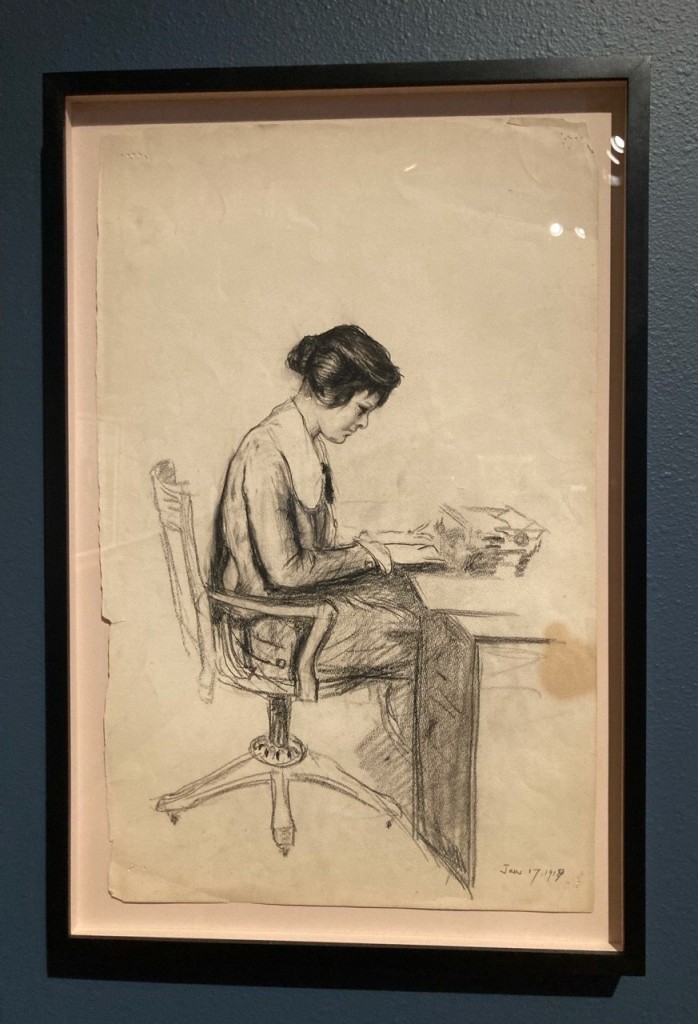

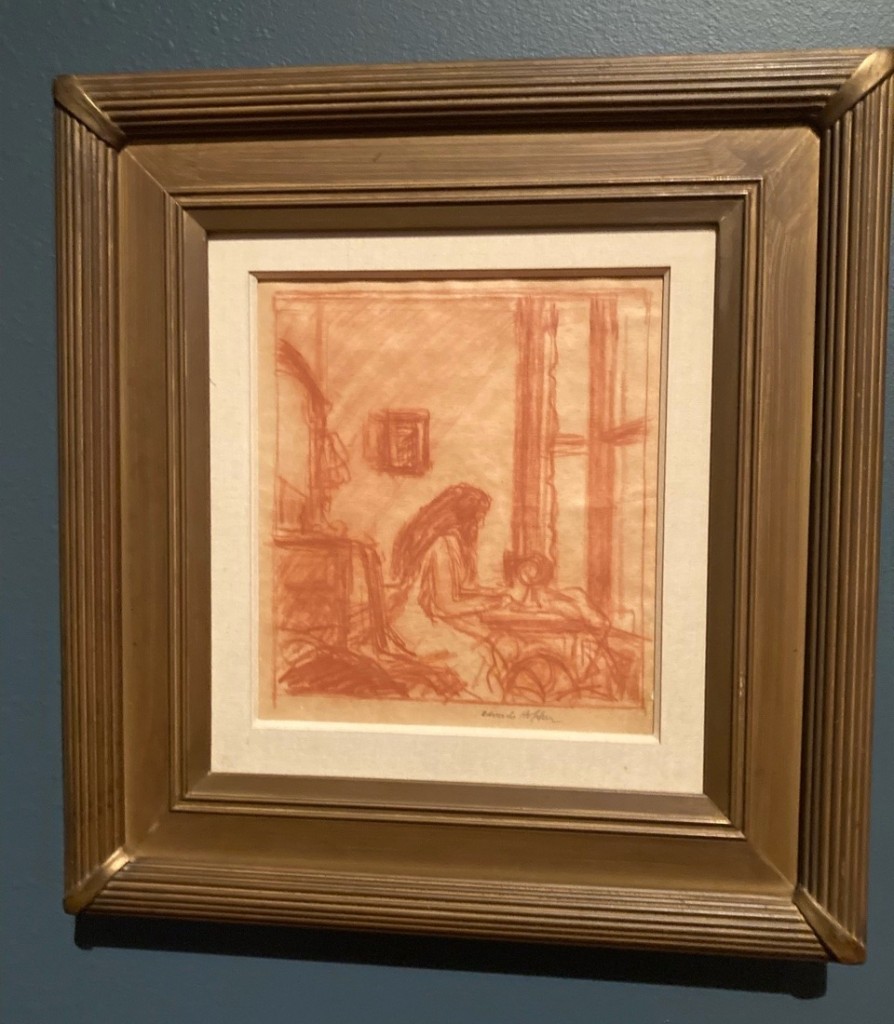

The two artists often chose similar subject matters. Sometimes these works eerily echo each other. For example, there is a charcoal and graphite on paper called The Typist (1918-19) by Pène du Bois and a conte crayon on paper entitled Girl at the Sewing Machine (1921) by Hopper that both show a similar tenderness toward a woman hunched over her work.

At other times, though, the works – despite the same settings – offer a stark contrast in their artistic visions. In a 1920 Hopper etching called Les Deux Pigeons (named after a ballet about a squabbling couple), a couple is intertwined on a cafe terrace overlooking the Seine as a waiter looks on.

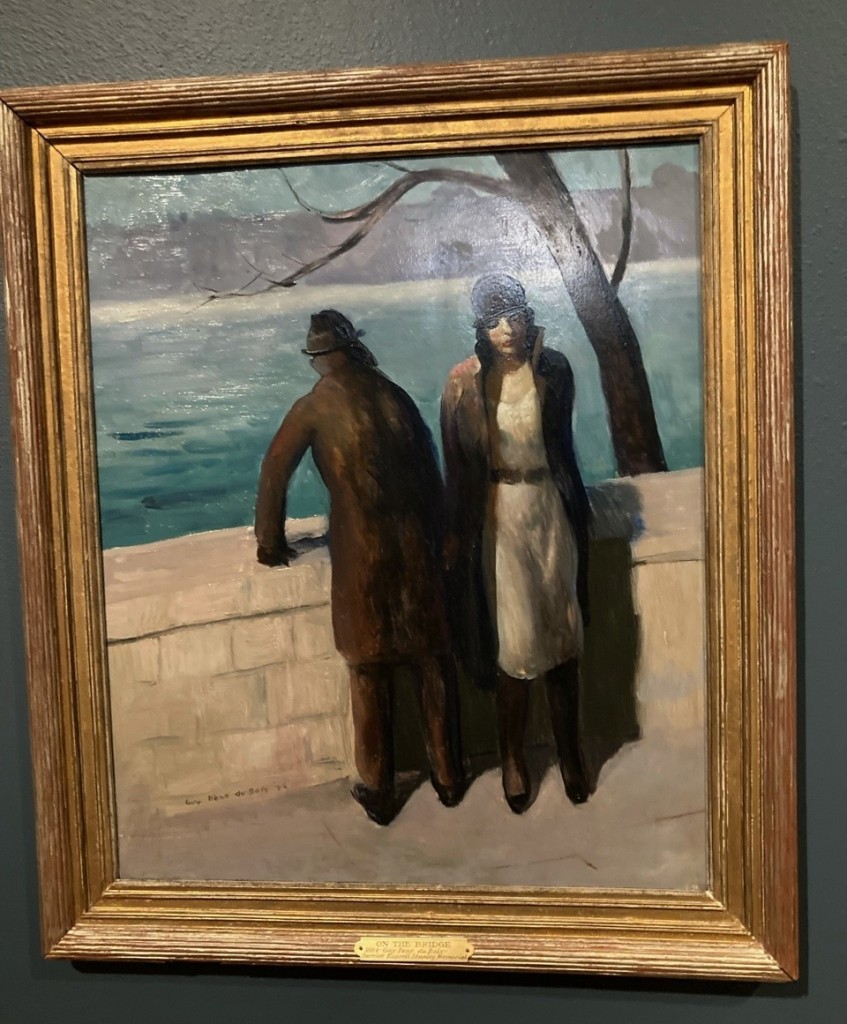

In a 1926 Pène du Bois oil entitled On the Bridge, a couple overlooking the Seine — a flapper with a cloche cap looking straight ahead and a gloved man leaning on a stone wall with his back to her— are clearly estranged.

Both Pène du Bois and Hopper remained devoted Realists throughout their careers, although each interpreted that style in a very different way. Hopper’s works, as the curators point out, are a masterclass in compositional structure and the use of light while a heightened style of figuration and bold use of color are at the core of Pène du Bois’ realism.

After World War II, surrealist and then abstract and conceptual art became seen as the cutting edge of modern art. Realist works began to fall out of favor.

This changing tide “may help account for the fading opportunities for Realist artists to shine, but how do we explain the sharply varying degrees of name recognition for Hopper and Pène du Bois today?” is the cogent question posed on one of the exhibit’s wall panels. It is appropriately entitled A Fickle Art World: Fame and Legacy in Modern Art.

“The whims of history are never easy to explain,” the blurb admits, but two possible explanations are offered for why Pène du Bois’ legacy faded. First, his six-year sejour in Paris with his family may have taken him out of the American art scene for too long. Second, his career as an art critic, writer and translator may have hurt his recognition as a visual artist. Pène du Bois split his time between his artwork and his other pursuits while Hopper worked full-time in his Greenwich Village studio.

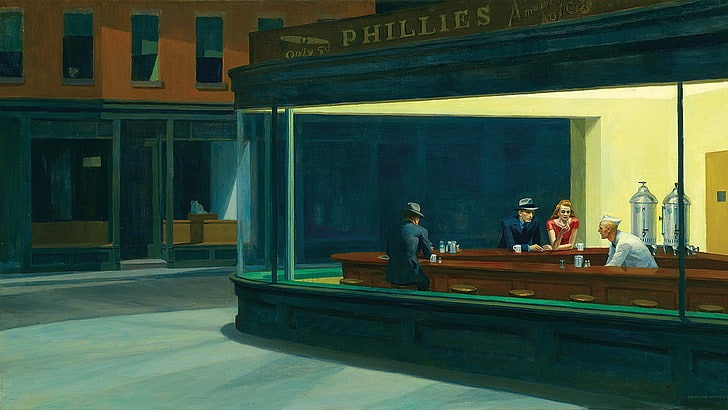

Could be. But I think there is simpler reason for Hopper’s enduring fame over his equally talented Realist colleague – Nighthawks, Hopper’s painting of four figures in a well-lit cafe on a dark street, painted in 1942. That painting (in the Art Institute of Chicago’s permanent collection and not included in the Polk show) is not only Hopper’s most famous painting – it is arguably one of the most recognizable paintings in American art.

But ironically, the fame of that iconic painting is not only due to the painting itself — which admittedly is spell-binding — but also because it gave rise to so many parodies.

The first was in 1984 when Gottfried Helnwein in Boulevard of Broken Dreams swapped out Hopper’s original four solitary souls with the faces of Marilyn Monroe, Humphrey Bogart, James Dean and Elvis Presley. (Notably when we asked a guard about Nighthawks, he brought up this infamous reworking of the piece). Dozens of send-ups have followed, subbing in casts from Star Trek to the Simpsons.

At the Polk show Nighthawks is only mentioned in passing in a museum label for a curious work called Light Battery at Gettysburg, one of two historical paintings by Hopper which he completed in 1940 – “Two years later Hopper would paint his most famous work,” the museum label reads. “Nighthawks is far more oblique than Light Battery at Gettysburg in its reference to the United States in wartime, with many arguing that the painting alludes to the solemness of life in America as many men and women went off to war.”

. . .

These days not many people would describe Nighthawks as a wartime painting. It is more commonly heralded as a perfect image of the loneliness of urban living. But whatever Hopper originally intended to convey in Nighthawks, the painting and its parodies have ended up guaranteeing his legacy, proving indeed just how fickle fame in the art world can be.

Guy Pène du Bois himself worried about becoming one of the “forgotten artists.” From his portraits of sophisticates with their elongated bodies and chic fashions to his unique works inspired by a hurricane, Guy Pène du Bois certainly deserves to be remembered.

Happily, the Polk exhibit does just that.

. . .

. . .