July 12, 2021 | By Tom Winchester

. . .

Expanding Waters, held at the Gallery at Creative Pinellas from May 17 until June 13, 2021, demonstrated how art contributes to society. The collaborative artists Mickett-Stackhouse created an environment where viewers were welcome to participate in a discussion about the climate crisis.

In the gallery, viewers could see paintings and drawings, walk through an installation, and even contribute their own drawings and writings about how we all can help to combat climate change.

Mickett-Stackhouse also invited artists in the performing arts, and scientists specializing in the environmental sciences, to contribute scheduled events over the course of Expanding Waters. Some events were pre-ticketed performances viewable only in-person, and others were available as online streams on Facebook Live. The exhibition fostered a discussion about climate change, and motivated its participants to do their part in mitigating it.

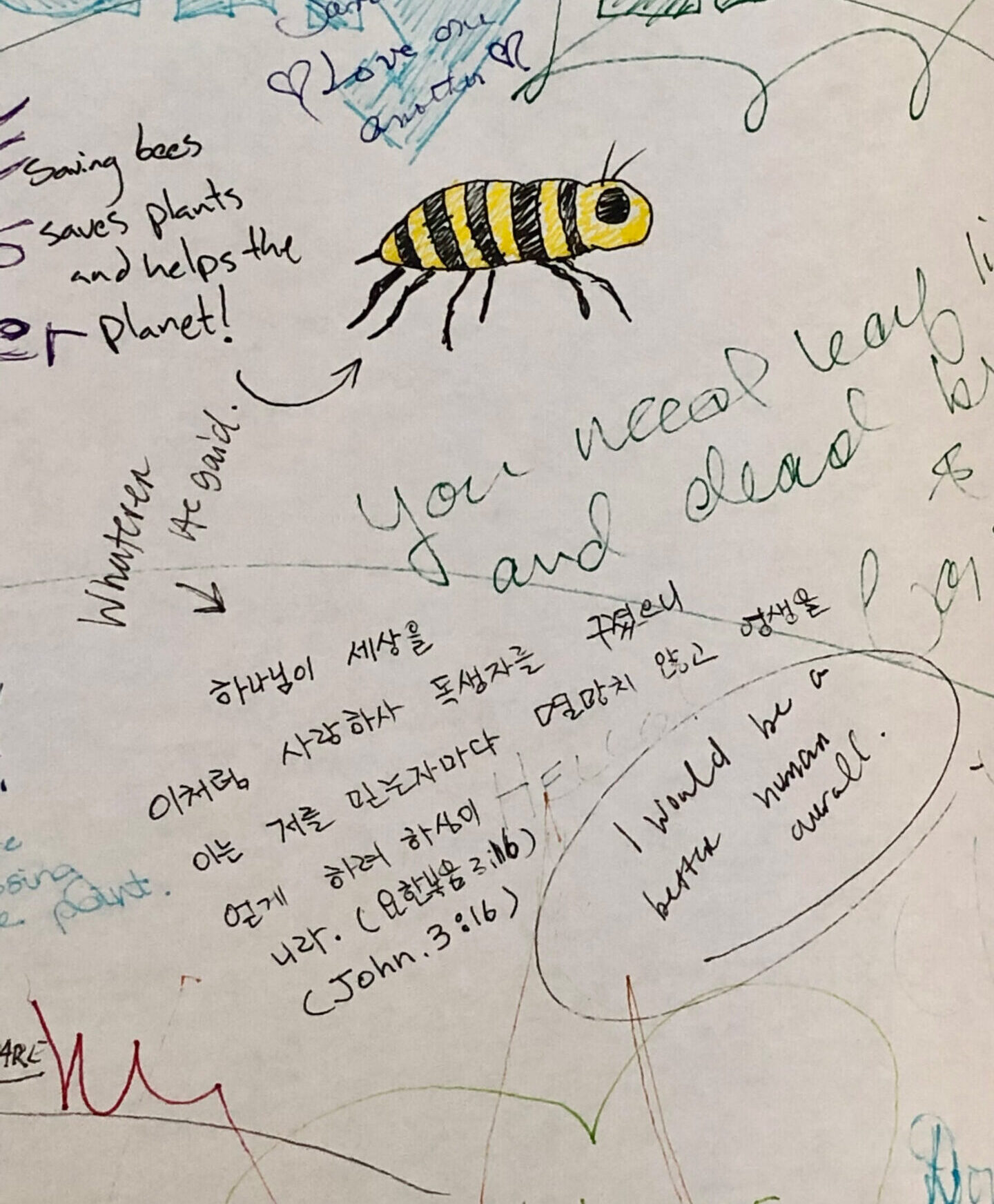

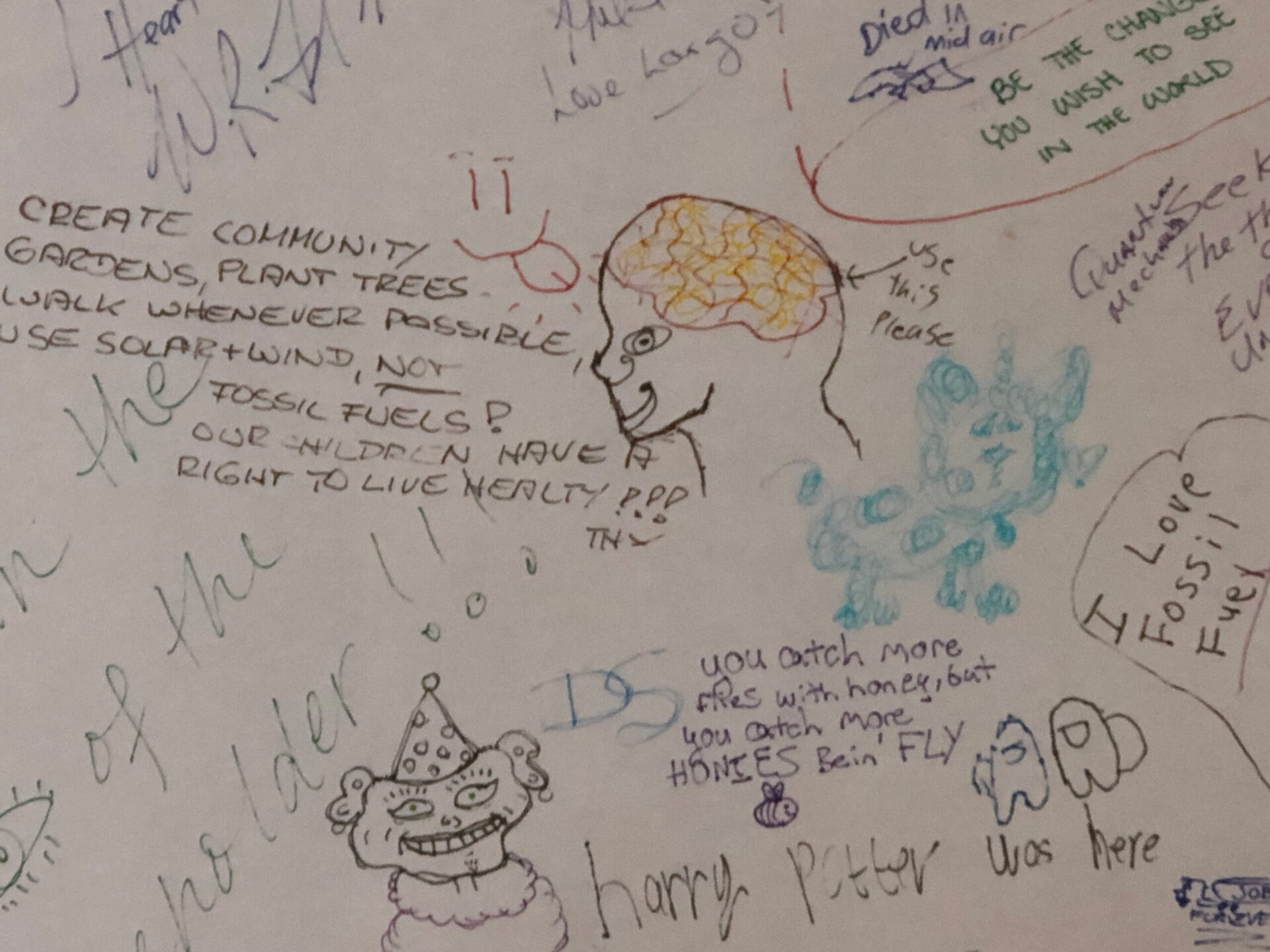

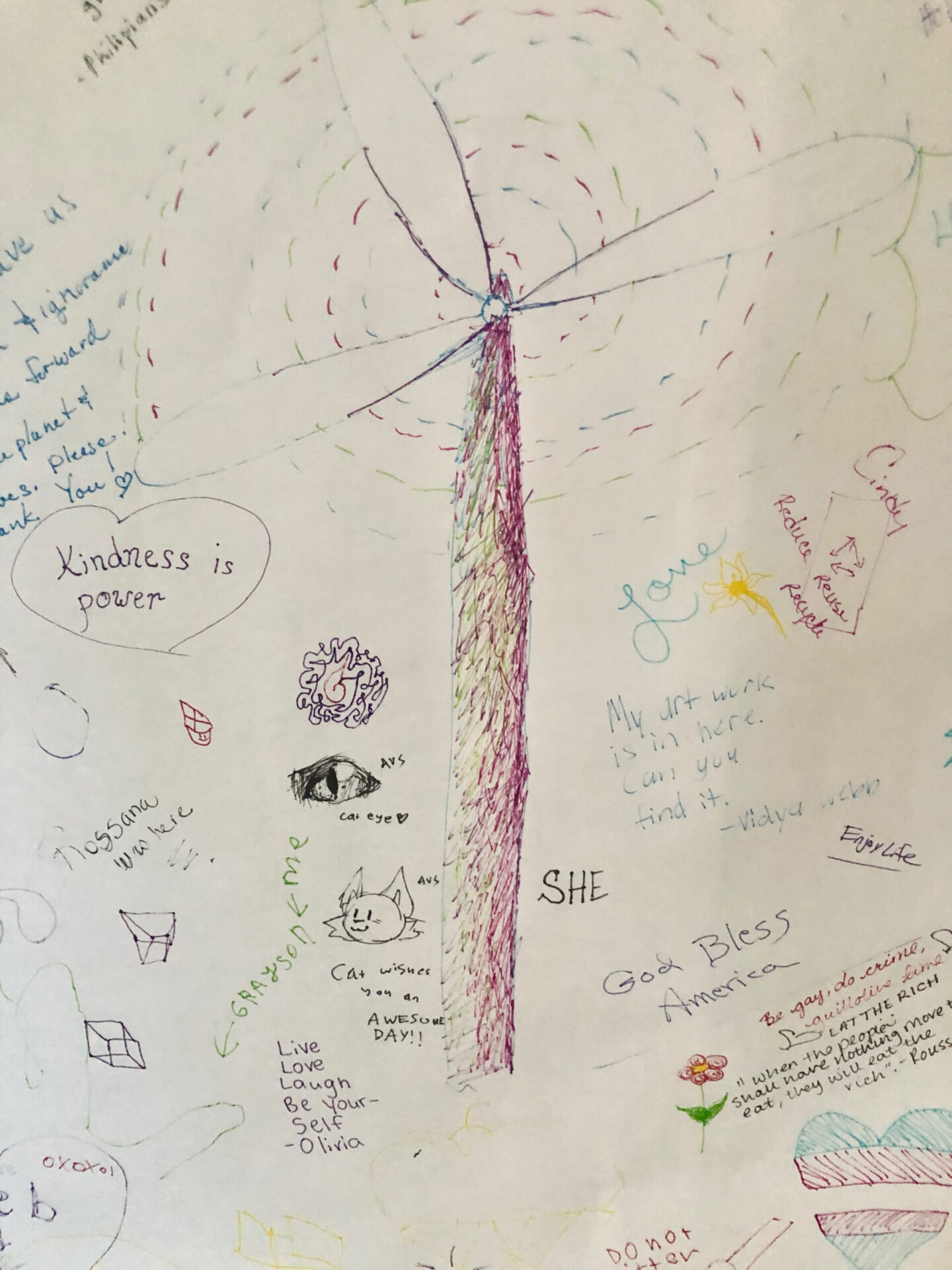

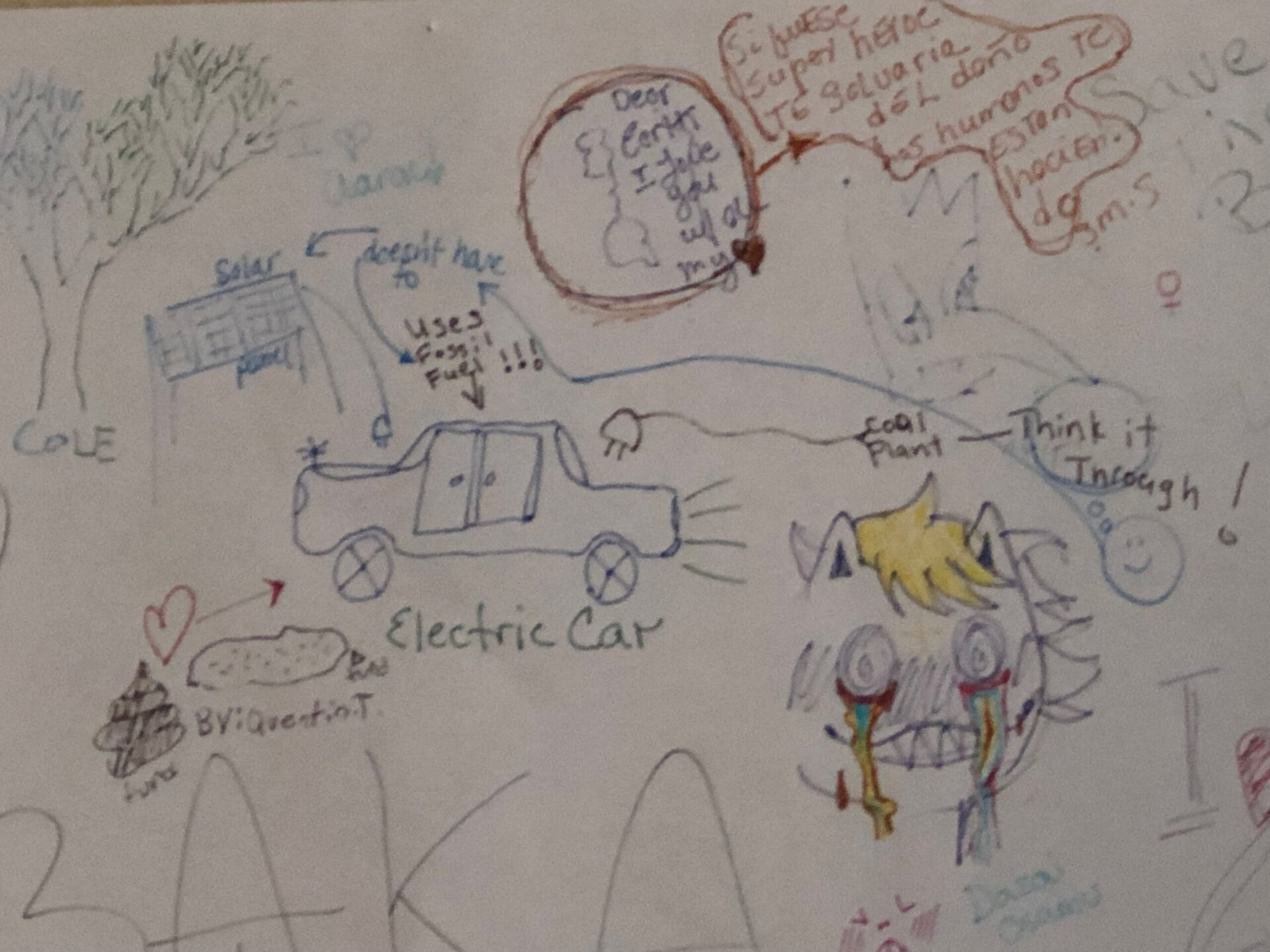

Many people contributed to Expanding Waters. The exhibition was initiated by Mickett-Stackhouse, who exhibited paintings, drawings and an installation titled Breath of Influence (2021). They also provided a room with pens, pencils and papered walls where gallery-goers could freely write and draw their responses to a prompt of, ‘What can I do to help combat climate change?’

. . .

. . .

In order to further develop a situation where viewers would be offered a variety of entry-points into the discussion of climate change, Mickett-Stackhouse invited performing artists and scientists to contribute their ideas to the exhibition. By involving such an array of contributors, viewers from various walks of life were offered an opportunity to interpret the exhibition’s themes in a way that speaks to them.

The performances consisted of actors playing a suite of works from Shakespeare called Sweet the Moon, and a program of choreographed dances conceptualized by Paula Kramer called Breathe. Both were performed to a live audience inside the gallery, and required advanced tickets. The science-related panel discussions were comprised of scientists and environmentalists discussing the causes of climate change, and how sea-level rise affects Florida’s coastal communities. The panel discussions were offered as virtual experiences on Facebook Live.

After the pandemic-forced shut-downs, the task of creating an exhibition of artworks, including an on-site installation that viewers would safely experience, assuredly required careful considerations on everyone’s part at The Gallery at Creative Pinellas. For the majority of the duration of Expanding Waters, in-person viewers were required to wear masks and maintain social distancing while in the gallery. Those who didn’t feel comfortable visiting in-person were invited to participate online.

The virtual experiences of Expanding Waters were especially useful in the exhibition’s earliest days before the vaccines were available to the general public. The hybrid model allowed for changes in policies and procedures over the course of the last few months, as things have become safer and more people have felt comfortable visiting interior communal spaces.

Sweet the Moon was performed on three consecutive evenings with the premier on April 23. The suite of scenes from more than half a dozen works by Shakespeare was directed by Dee O’Brien, and featured a company of about a dozen players. Its eponymous line from The Merchant of Venice reads, “How sweet the moonlight sleeps upon this bank!”[1] The line serves as the image linking the themes of the vignettes from Shakespeare with the depictions on view in the gallery, especially, The First Moon (2012).

The vignettes included Carol Mickett and Bruce Miller playing a scene from the Merchant of Venice, Nathan Attard and Graham Jones playing a scene from King Lear, Leigh Davis reciting a compilation of sections of verse from three separate works, and Michael Cote Jr. and Katerina Lecourezos embodying the star-crossed lovers, Romeo and Juliet.

The suite was played as if in a black-box theater. The sets were comprised of a combination of the contents of the gallery, including Breath of Influence – and the viewers’ imaginations. Players interacted with the installation by entering and exiting through the ring in the center, and hiding behind its vertically hanging strips of paper tape. The players also interacted with the paintings hanging on the walls of the gallery as if they were elements of the set. For example, The First Moon played a role in the scene from Romeo and Juliet with the lines, “O, swear not by the moon, the inconstant moon…”[2] Interspersed with the played scenes were dance performances by Fernando Chonqui.

Mickett-Stackhouse also collaborated with choreographer Paula Kramer, who contributed a dance program titled, Breathe. Performed on two consecutive evenings beginning on May 27, the program included ensemble performances, and individual solos by each dancer. All the while, John O’Leary provided gorgeous live piano accompaniment, original music he composed on site while watching the dancers rehearse. Helen Hansen French performed a solo titled, Moon Tide, Sea Lee performed Tidal Force and Rachel Lambright performed 212° F.

At times, the dancers were among the seated viewers, as if there were no distinction between where their world ended and ours began. One theme the dancers repeated throughout the program was a succession of thrashing and jerking motions in the direction of The First Moon. The effect was as if the dancers’ limbs were being pulled and repositioned by the Moon’s gravity. In this way, the dancers were embodying the water of the ocean. They were enacting a representation of the interconnectedness of our planet. It also seemed like the thrashing and jerking motions became progressively more violent as the performance went on. Especially when juxtaposed with Imbalance of Fire (2020), the increasingly violent thrashing symbolized how climate change, specifically the warming of our waters, is causing more intense storm systems.

The science panels contributed a non-art entry point for participants of Expanding Waters. They offered a perspective on climate change that most people rarely have access to. Climate scientists were able to speak to the community directly about the causes of climate change, and make suggestions on how we as locals can help to mitigate its effects.

These three panel discussions hosted by Carol Mickett were offered online via Facebook Live. Such an experience has become commonplace in the COVID-19 era – virtual events held live for the purpose of discourse with the viewership, that are offered to a wider audience as recorded videos for viewing at a later date. For the purpose of Expanding Waters, these recorded panel discussions are readily accessible for future viewers to have reliable, scientifically accurate entry points into the causes of climate change.

. . .

. . .

Carol Mickett introduced the first science panel on March 27, titled, “What is Climate Change and Sea-Level Rise?” by saying, “Art is a great way to create a story, and it engages people in conversation. . . But our conversations can go just so far. To keep them going, to discover the depth of these issues, to learn the causes, the ongoing facts and the details of solutions, we must turn to the scientists who spent their lives researching, experimenting and ruminating in scientific creativity.”[3]

Libby Carnahan, member of the Tampa Bay Climate Advisory Panel, gave an overview of climate science, and spoke specifically about the vulnerability of an overly developed Pinellas County to the effects of climate change. Gary Mitchum told us the sea level has risen about six inches since World War II. Davina Passeri studies the coastlines, and recommended ways to mitigate future hazards like flooding and erosion.

. . .

. . .

The second science panel, “What Can You and I Do About Climate Change?” held on April 17, began with Creative Pinellas CEO, Barbara St. Clair, celebrating the dialogic characteristic of Expanding Waters. “One of the things being demonstrated and built by this project, that Carol and Robert have spearheaded, is the collaboration between artists, scientists, socially-minded thinkers, audiences, and everyone watching online or coming to the gallery.”[4]

Susan Glickman emphasized the importance of electing representatives who will support environmentally friendly legislation. Dory Larsen told us the transportation sector of the economy recently overtook the utility sector as the leading contributor of carbon dioxide pollution in the United States, and described how driving an electric car can help to reduce the global warming effect of greenhouse gasses. Doris Heitzmann discussed how Florida-friendly landscaping can save water and energy, reduce pollutants, provide habitats for animals and assist recycling. She remind us to, “Think globally, act locally.”[5]

. . .

. . .

The third science panel, “What is a Green Society,” held on May 8, outlined what an environmentally friendly utopia would look like. JP Gellerman stressed how urban planning is necessary for developing a healthy environment. Lara Thomas drew up the systemic ways communities can implement sustainability and resilience that mitigate climate change.

Barbara St. Clair asked a simple question, “What does art have to do with it?”[6] Her presentation outlined art’s role in society, and featured a graphic illustrating Creative Pinellas’s role in fostering art and the careers of local artists. She described the role Creative Pinellas plays in the local community as one that helps to facilitate disparate connections in the local network of businesses, nonprofits, philanthropies and individuals, and she expounded on the role of art-related institutions in society as a whole. “We are the messenger RNA of the world.”[7]

. . .

Aesthetically, Expanding Waters can be understood as exemplary of a form of art called social practice. Mickett-Stackhouse created a situation where several contributors, both artists and non-artists, interpreted the exhibition’s main themes in new forms. Its contributing participants were prompted to act upon those themes as they went about their lives.

Social practice allows professional artists to ‘direct’ participants of an artwork without unilaterally determining that artwork’s ultimate form. The term was institutionalized in 2005 when California College of the Arts created an MFA concentration in Social Practice. The art form became trendy in 2008 with the Guggenheim Museum’s group exhibition titled, theanyspacewhatever, which included one artist who turned the spiral gallery into a hotel. Jerry Saltz spent the night there, and raved about the experience in New York Magazine. “This cheekily titled outing is devoted to a clique of artists who reengineered art over the past fifteen years or so. They created the most influential stylistic strain to emerge in art since the early seventies. Their impact can be seen in countless exhibitions.”[8]

. . .

. . .

Considering their collaborative efforts as an example of social practice, in my opinion, helps to characterize the oeuvre of Mickett-Stackhouse within a specific style. There are lots of moving parts to most Mickett-Stackhouse artworks, and they incorporate various media. Sometimes their collaboration produces traditional media like drawing, painting and sculpture viewable in public settings like parks and lobbies of buildings owned by major businesses. Other times their collaboration produces immersive installations and spaces for fostering community discourse. Understanding their collaboration as social practice may be the way to most fully describe the style of Mickett-Stackhouse in contemporary terms.

Fundamentally, an artwork in the vein of social practice activates the viewer from an otherwise passive position. Artworks in this vein require viewer participation. Art critic Claire Bishop has written extensively about how art since the turn-of-the-millennium has shown a tendency toward viewer participation. In her 2012 book, Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, Bishop explains the artists’s role in participatory art is, “[A]s a collaborator and producer of situations; the work of art as a finite, portable, commodifiable product is reconceived as an on-going or long-term project with an unclear beginning and end; while the audience, previously conceived as a ‘viewer’ or ‘beholder, is now repositioned as a co-producer or participant.”[9]

. . .

. . .

. . .

Participatory artworks are effective, Bishop claims, because they empower social change.[10] In the introduction to the 2020 collection of essays titled, Social Practice Art in Turbulent Times: The Revolution Will Be Live, editors Eric J. Schruers and Kristina Olsen point to social change as one of the primary motivators for artists working in this vein. “The implicit desire to effect immediate social and political change has led to a drive for direct creating and making — on the streets and in focused interaction with the people of a community — where everyone is an artist and everyone contributes through participation.”[11]

In effect, Mickett-Stackhouse take the fact that the viewer plays a collaborative role in the creation of artworks as self-evident. It’s hard to find a component of Expanding Waters that doesn’t have a participatory aspect. The allegorical paintings and drawings serve as entry points for viewers to come to new conclusions about climate change and then be motivated to do something about it.

. . .

. . .

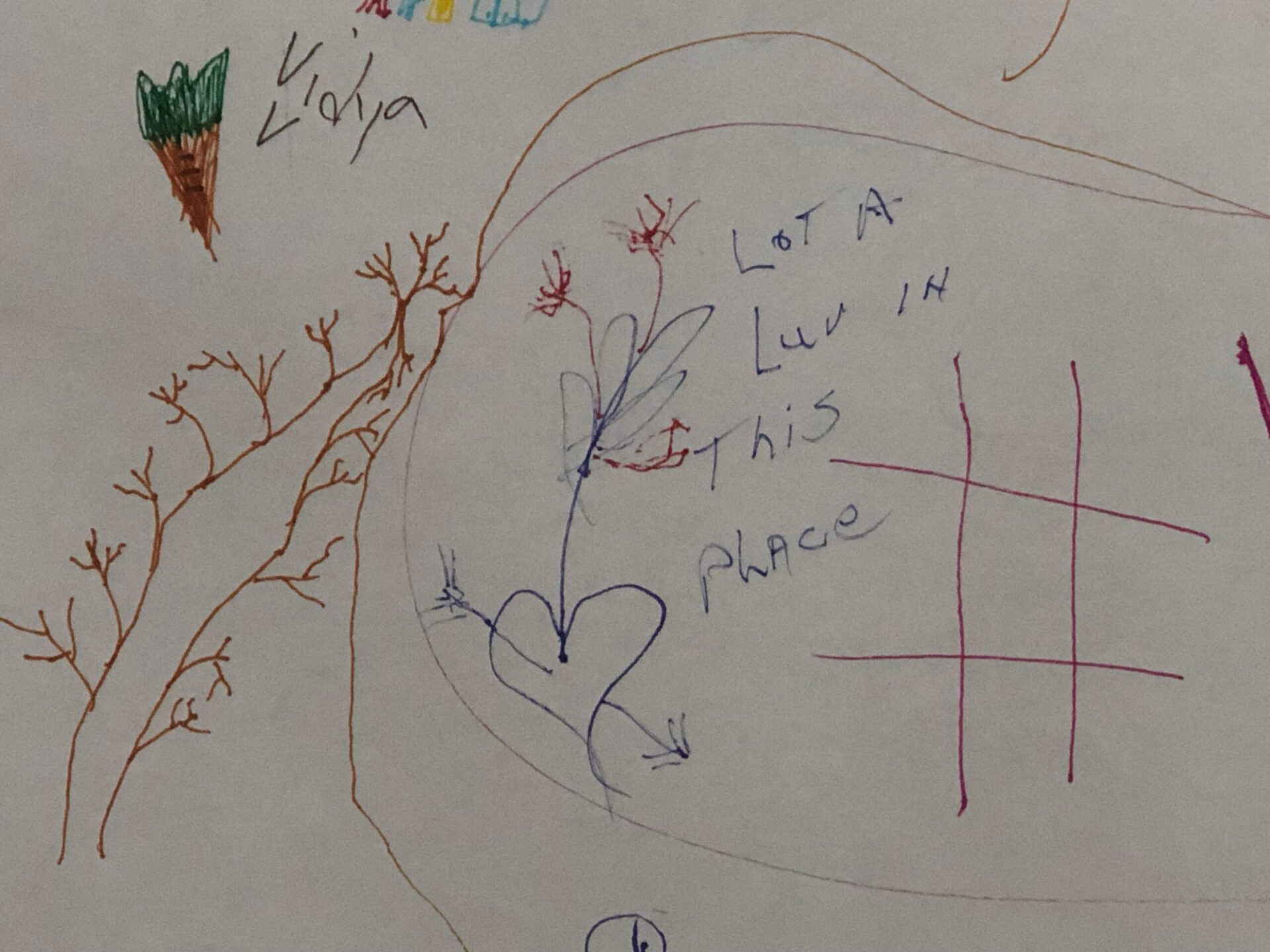

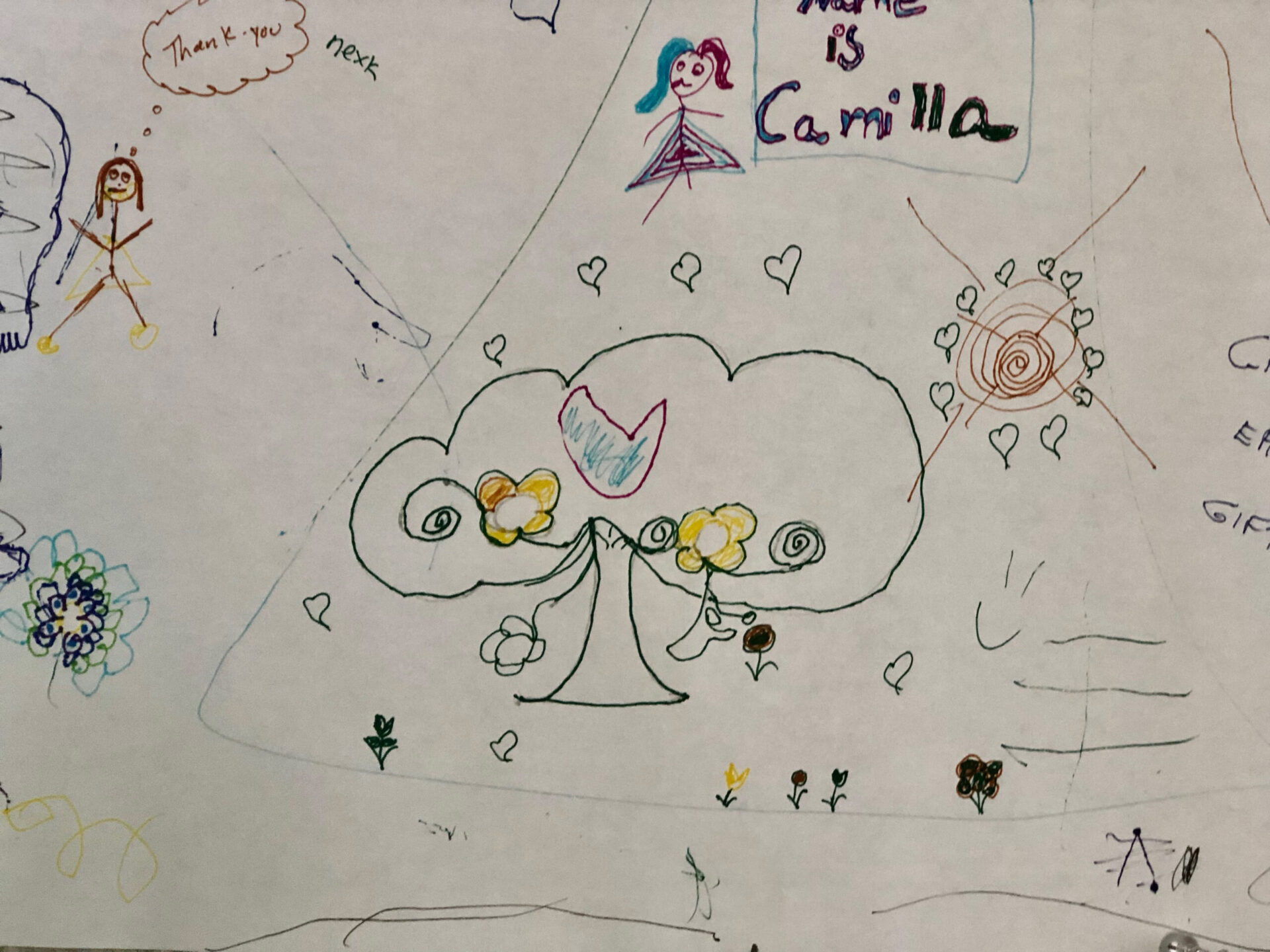

Breath of Influence is activated by the movement of the atmosphere from passers-by, and sways with the flow of those who are walking near it. Yet, the most overtly participatory situation offered by Expanding Waters was initiated by providing drawing utensils and mural-sized sheets of paper in one of the gallery’s rooms. The Gallery-goers were prompted to draw and write about how they can help to combat climate change – and by the time the exhibition’s closing reception came around, the sheets of paper were full of drawings and writings from the community. Mickett-Stackhouse offered these materials, and the space, so viewers would be given the opportunity to directly participate with the exhibition.

Including theatrical performances and science-related panels to Expanding Waters fulfilled both primary characteristics Bishop named as typical of participatory artworks – delegated performance and pedagogy. By collaborating with a director and company of actors for Sweet the Moon, and a choreographer and a company of dancers for Breathe, Mickett-Stackhouse initiated situations, “[I]n which everyday people are hired on behalf of the artist…”[12] By hosting three panel discussions with climate experts on the online platform Facebook Live, which allows for comments and questions, Mickett-Stackhouse fostered a forum, “[I]n which art converges with the activities and goals of education.”[13]

. . .

. . .

. . .

These participatory components, coupled with the activistic prompt of combatting climate change, are possibly the most persuasive characteristics of Expanding Waters in considering the exhibition as social practice.

Expanding Waters can serve as a standard for how art fosters local community discourse.

Now, after the paintings and drawings have been taken down, the installation has been disassembled, and the actors, dancers and musicians have gone home, the art of Expanding Waters takes form in the actions of those who continue to be motivated by its influence.

. . .

[1] William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, Act 5, Scene 1

[2] William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act 2 Scene 2

[3] https://www.facebook.com/CreativePinellas/videos/1196910187378904

[4] https://www.facebook.com/CreativePinellas/videos/322340369228219

[5] https://www.facebook.com/CreativePinellas/videos/322340369228219

[6] https://www.facebook.com/174973145925396/videos/3826132627464065

[7] https://www.facebook.com/174973145925396/videos/3826132627464065

[8] Jerry Saltz, NY Mag 2008 https://nymag.com/arts/art/features/51998/

[9] Claire Bishop, Artifical Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (Verso, London, New York: 2012), 2.

[10] “[P]articipatory art is perceived to channel art’s symbolic capital towards constructive social change.” Bishop, 13.

[11] Eric J. Schruers and Kristina Olsen, Social Practice Art in Turbulent Times: The Revolution Will Be Live (Routledge, New York, NY: 2020) Introduction.

[12] Bishop, 4-5.

[13] Bishop, 4-5.