Bruce Davidson (b. 1933) may not be a household name like Ansel Adams (1902-1984) or Dorothea Lange (1895-1965), but he is responsible for creating iconic images readily identifiable and familiar to anyone who follows news or history.

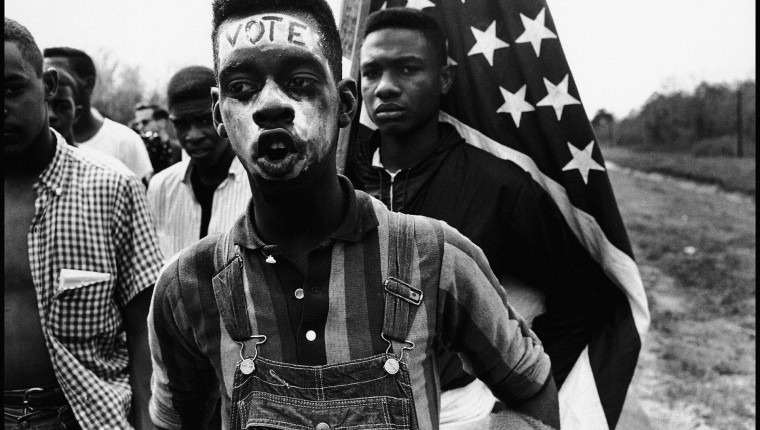

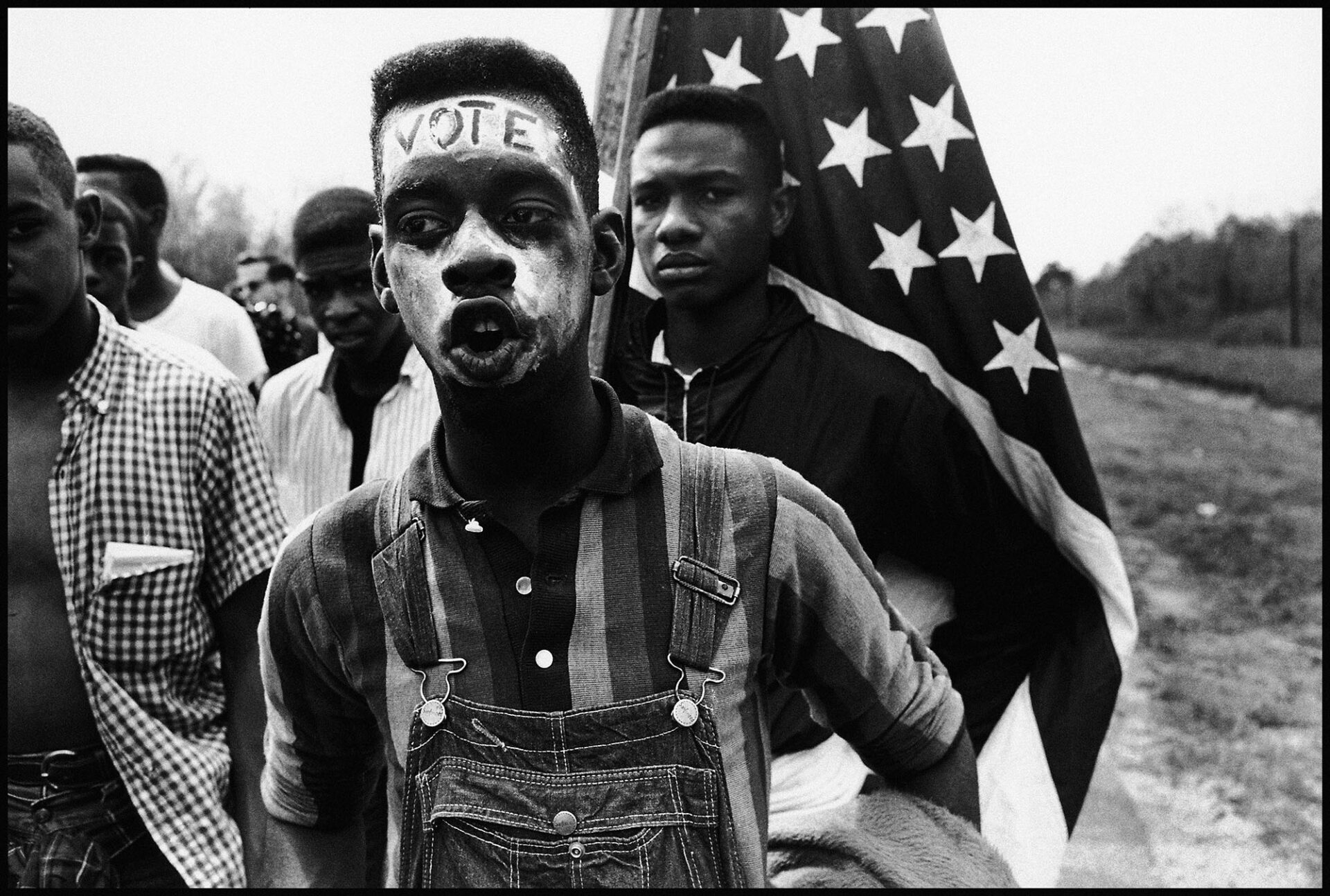

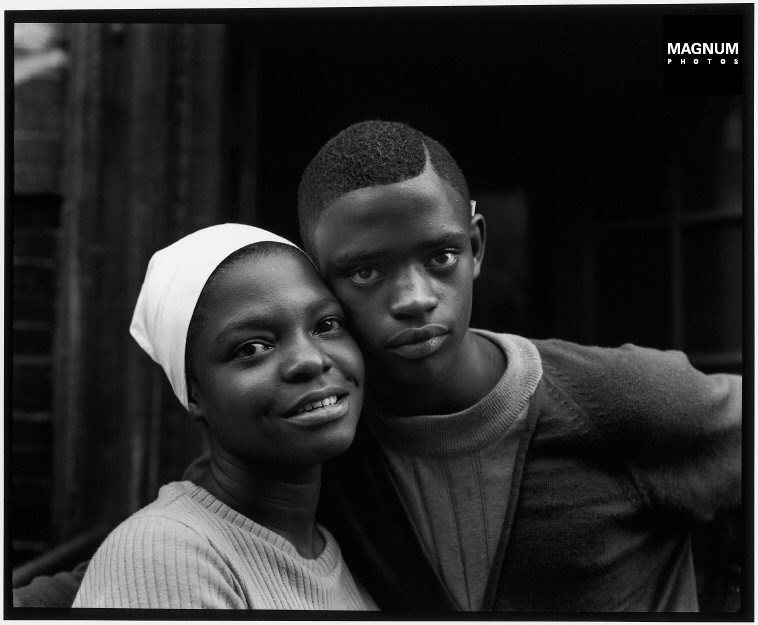

His photographs of the Freedom Marches of the 1960s continue to be used to describe the struggle for equality among races and social strata to this day. His images of Jimmy Armstrong, performer and little person with the Clyde Beatty Circus in 1958 New Jersey, still evoke how it must feel to be an outsider.

Born in Oak Park, Illinois, Davidson overcame a difficult childhood and a broken home by taking up the camera at the age of 10 and using it as a way of expressing his own dark and outsider feelings. He typically chooses subjects that are unusual or people displaced by society.

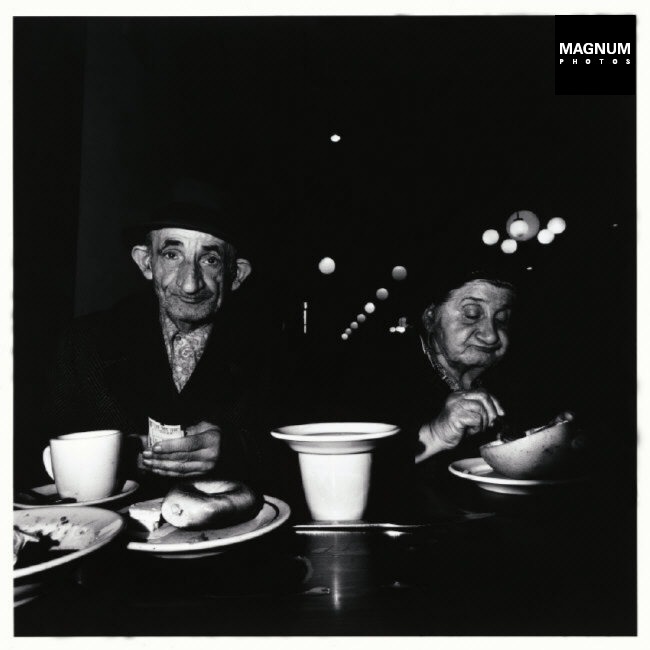

One of his earliest photographic series in 1953 focused on the Light House Mission, a soup kitchen, and the down and out patrons who gathered there. He credits W. Eugene Smith (1918-1978) as one of his greatest influences and was undoubtedly inspired by Smith’s photo essays in LIFE magazine to create his own distinctive style of visual sociology.

Unlike many of the street photographers of the 1960s and 1970s who would prowl the streets and catch random shots of humanity, Davidson would immerse himself completely within a specific group of people or a location for months or even years at a time, enabling him to capture intimate and personal images that explored each subject in depth.

After short stints at the Rochester Institute of Technology, Yale University and the Army, Davidson worked briefly as a photographer for LIFE magazine. Starting with freelance assignments, he was offered a staff position in 1958 but turned it down. Davidson was committed to creating his own meaningful work instead of assignments from an editor, even if it meant refusing a position with one of the most prestigious of magazines at the time.

Instead, he turned to Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004), the famed French photographer known for his photographs capturing the “decisive moment,” and a great inspiration to him.

While serving in the army in 1956 France, Davidson had approached Cartier-Bresson with a photo series he created featuring the elderly widow of the impressionist painter Léon Fauché (1868-1950). This Widow of Montmarte series offered a dark glimpse into a romantic Paris of the past.

Cartier-Bresson reviewed the work favorably, and the two photographers established a loose informal relationship. In 1947 Cartier-Bresson, along with Robert Capa (1913-1954), David Seymore “Chim” (1911-1956), and a few other leading photojournalists of the time formed the photo-cooperative Magnum. By banding together, the artists were able to retain the rights to their own pictures, and maintained control of both their use and sources of funding.

Two years later, at the age of 24, Davidson used this same Montmarte series and the approval of Cartier-Bresson to apply for membership to Magnum. He was made an associate member, and one year later became the youngest full member of the agency.

It was through contacts at Magnum that many of his most meaningful series were established. The solitude and otherness of a clown in a New Jersey circus in 1958, and a gang of teenagers acting out in 1959 Brooklyn, are among his early successful subjects. With the latter he spent almost an entire year hanging out with and documenting their emotional isolation, which in many ways reflected his own.

Davidson considered himself an outsider and in an interview in the New York Times in 2003 he remembered: “they had allowed me to witness their fear, depression, and anger. I soon realized that I, too, was feeling their pain. In staying close to them, I uncovered my own feelings of fear, frustration, and rage.” The series sold to Esquire magazine in the U.S. and DU, in Europe.

This success led him to assignments with the fashion magazine Vogue, acting as one of the onset photographers for the film The Misfits starring Marilyn Monroe, and what would become some of his most recognizable work – the opportunity to cover the Civil Rights struggles first hand.

In 1960, Davidson volunteered to cover a Freedom Rider bus trip for Magnum after news broke that a trip had ended in a fire bombing and brutal assaults. He rode from Montgomery, Alabama to Jackson, Mississippi with fellow riders of all colors, as well as state troopers posted on board for protection. While they were not assaulted, everyone on board was arrested at the terminus.

His Civil Rights photographs of this era illustrated for the rest of America the brutal prejudice that existed in the South, which had been an abstract notion for many. He went on to document the poverty of the South, the Ku Klux Klan, subsequent Freedom Rides – and captured Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech on the National Mall in Washington, DC. These images were used to inspire, motivate, and educate people around the world.

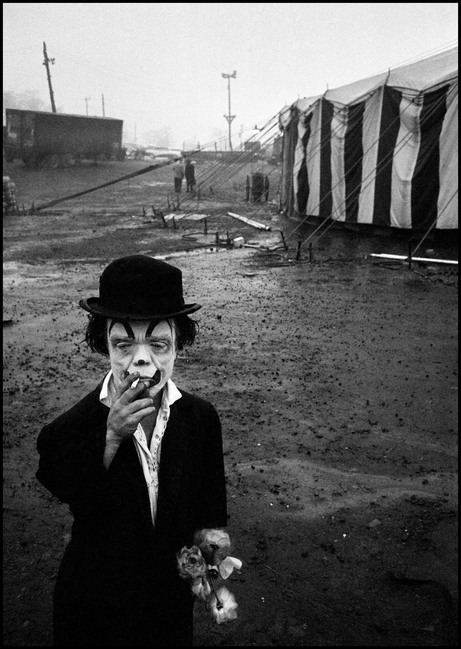

This insight into Southern poverty and the costs of prejudice to society, led to his series, East 100th Street. From 1966 to 1968, Davidson witnessed the dire social conditions on a single block of East Harlem, New York, which was considered by many to be the worst in Manhattan, plagued by poverty and crime.

To gain trust as an outsider, he presented himself to the Metro North Citizen’s Committee, a self-regulated group of volunteers focused on improving the neighborhood. After seeing his respectful images, they granted him access, sometimes even accompanying him as he knocked on the doors of strangers asking if they would pose for a picture.

He used a large format camera on a tripod to add more importance to the project. The resulting images portray a grace and dignity even within the terrible social conditions he encountered. The photographs were used by community activists to illustrate the desperate circumstances people lived in.

A member of the Metro North group wrote in the forward of the 1970 publication of these photos in book form, “When we went to meetings outside of East Harlem, we brought Bruce’s pictures. I took East 100th Street with me to city agencies. I showed them the way we were living and what we needed.”

In 1998, Davidson was awarded the Open Society Institute Fellowship to return to the same block and make note of the changes that three decades of slow, but concerted, urban renewal had achieved.

In 1980 Davidson spent months underground roaming the graffiti-laden and notoriously dangerous New York subway system. Around that time the NYPD was recording up to 250 felonies a week there. The Lexington Avenue Express was dubbed the “mugger’s express.”

Davidson spent months preparing – increasing his fitness routine, acquiring police and subway passes, gathering a kit that included a pocketknife and whistle, and creating a small album with portraits to show potential subjects. While he was never injured, he was subject to muggings.

He never concealed his camera like some earlier subway photographers including Walker Evans (1903-1975), who notoriously hid his camera underneath his topcoat with the lens peeking out between the buttons.

Davidson would politely ask to take a photograph and then offer to follow-up by sending the person a copy. And while his early work was almost entirely shot in black and white, the Subway series is in glorious Kodachrome 64 color. His objective was to capture a microcosm of the city in all its vitality and visual complexity.

In 1982 these pictures were afforded an exhibition at the International Center of Photography (ICP) along with a photobook published by Aperture in 1986.

Currently, Davidson is 87 years old. He continues to work, pursuing nature series on Central Park, parks in Paris and nature in Los Angeles, yet he remains more engaged with how people use these spaces than the settings themselves.

In 2013, he photographed the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington. He has a remarkable body of work. There is no particular style or look that defines a Davidson photograph, but his empathy and humanity permeate every image.

Today, in this time of urban marches and the Black Lives Matter movement, Bruce Davidson’s photographs offer a heartfelt glimpse into our complicated past.

The exhibition Bruce Davidson: New York is currently on view at the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts in Tampa through January 2021.

This exhibition offers 60 vintage photographs focusing on six series Davidson created above and below the streets of New York City from 1959 to 1998. Photographs of the Civil Rights era and the circus, while not in this exhibition, can be viewed as part of a December 4 fundraising event.

Robin O’Dell curated the FMoPA exhibit, Bruce Davidson: New York

Explore Bruce Davidson’s work here

Find a New Yorker Q&A with Davidson here