Lately I’ve been experiencing Yogi Berra’s déjà vu all over again, that dreaded sense of being caught up in an endless loop like in the movie Groundhog Day.

Except that in this loop, the events that are being repeated are getting scarier and scarier.

I’m talking about the latest wave of book banning in Florida.

In 1991, I wrote a column about book banning in our state. I was then the book editor of the St. Petersburg Times.

“Poor Clay County. People there in rural North Florida are so ignorant that they wanted to ban My Friend Flicka from their elementary schools because it contains the words “damn” and “bitch.” Can you imagine? They also objected to William Steig’s Abel’s Island because it depicts a wine-drinking frog and — can you believe this one? — Little Red Riding Hood because that little girl on her way to grandmother’s house was carrying wine in her basket. How could anyone be so backward? Poor book-banning Clay County.”

“The inclusion of the Clay County cases on the American Library Association’s list of “Books Challenged or Banned in 1990-1991” certainly might give you the impression that its citizens are narrow-minded and backward. The ALA list, however, leaves out one important fact: Those parents in Clay County (and it was only two) were unsuccessful in their attempt to ban these books. The books were not used for two or three weeks while the Instructional Materials Review Committee, a group of about a dozen parents and teachers appointed by the School Board, reviewed the parents’ complaint. But then they were returned to the shelves, as the committee unanimously recommended.

Instead of receiving ridicule, Clay County should be commended for its fight against censorship.”

I am no longer book editor at the St. Petersburg Times. The newspaper isn’t even called the St. Petersburg Times anymore (it changed its name to the Tampa Bay Times in 2011). But after 32 years — 32 years! — there are still attempts being made to remove books from Florida school libraries. Except this time the challenges feel different.

Back in 1991, the process to hear out complaints about individual books, while worrisome, felt like democracy in action. Parents’ concerns were addressed. In many cases provisions were made so that they could choose to have their child’s access to the books restricted – but the books were placed back on the shelves for other children to read.

Now the attacks on books are more ominous, more organized and, alas, more successful. We are a long way from worrying about wine in Little Red Riding Hood’s basket. These aren’t just challenges to books with curse words and wine-drinking frogs in them. These are targeted assaults against whole categories of people. Today’s book banners are questioning people’s right to tell their own history — or to exist at all.

Last month in Hernando County after fifth grade teacher Jenna Barbee was reported to the state for showing her class Strange World, a Disney movie written by acclaimed playwright Qui Nguyen with a biracial, openly gay character in it, 600 people showed up to voice their opinions about book banning at a school board meeting that lasted eight hours.

“Men are to be men. Alpha males. Do you understand me? You have awakened all of the alpha male blood in this country with your leftist, woke ideology you’re pushing in here,” one man told those who were objecting to the removals of books with gay themes.

“We do not want to have equity and inclusion in our schools,” said Shannon Rodriguez, the school board member who reported Barbee to the state because parents were not notified ahead of time about the movie’s airing (Rodriquez’s child was in Barbee’s class). ”We want to keep our schools traditional, the way that they were, we don’t want any of the woke or the indoctrination.” During the last elections, Rodriquez was backed by the conservative group Moms for Liberty.

According to PEN America, which tracked book bans in schools from July 1 to December 31 of 2022, Florida ranks second – behind Texas – as the state with the highest number of book removals.

The number of removals in Florida may even be higher, the group pointed out, as new laws signed by Governor Ron DeSantis have encouraged broad, state-level “wholesale bans” that restrict access to “untold numbers of books in classrooms and school libraries.”

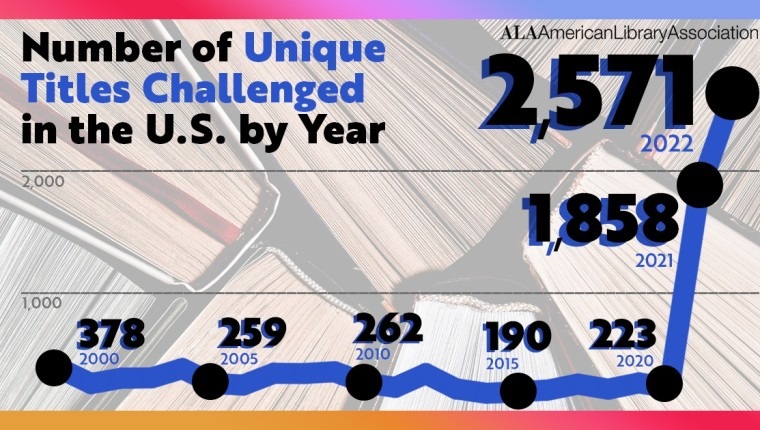

In March the American Library Association (ALA) reported that 2022 saw the highest number of attempted book bans (1,269) since ALA began compiling data about censorship in libraries more than 20 years ago, nearly doubling the 2021 number.

Of those titles, the vast majority were written by or about members of the gay and transgender community and people of color, according to ALA.

The fourth most banned book in America from the 2021-2022 school year was, in fact, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, the story of a Black girl who thinks she’s ugly because she doesn’t have blue eyes.

That was the book that prompted a complaint in January in Pinellas County, a complaint from a single Palm Harbor University High School parent. As a result The Bluest Eye was pulled off the shelves of Pinellas County Schools for three months.

Like my Clay County example in 1991, that request for censorship was eventually rejected — after parents and students came out in droves at a Pinellas County Board meeting to protest. And, as I did 32 years ago, Stephanie Hayes, a columnist at the Tampa Bay Times, congratulated the committee for weighing “the difficult scenes in context of its literary merit” and sending “this vital tale of a child’s lens on race in America… back where it started: in high school libraries for whoever wants it, and on select classroom syllabuses with the option for parents to opt their student out.”

But Hayes also added, “It’s all just so exhausting. It’s difficult to feel elated at the tail end of a drawn-out process that never had to happen.”

I’m feeling that same fatigue.

As the new Reading Rainbow Live suggests, keep making art!

And clean up afterwards.

. . .

What are the book banners afraid of?

“Well, we all know: They are afraid of readers — especially young readers — learning the truth about humans, about American history, about, perhaps, their own lives,” Jane Smiley, author of A Thousand Acres, wrote in a recent article in The Nation.

“If you’re afraid of knowledge, if you want to ban books, you’re not afraid of the books, you’re afraid of learning,” agreed LaVar Burton, founder of the popular PBS series Reading Rainbow, in an online talk at the L.A. Times Book Club to discuss the State of Banned Books with Times editor Steve Padilla. “This is very punitive and very puny. It’s small of soul to ban books.”

Burton, famous for his role as Geordi La Forge in Star Trek: The Next Generation and Kunta Kinte in the miniseries Roots, for decades was the host of Reading Rainbow, a program that encouraged the love of reading and books among children.

Last year the series was revived as Reading Rainbow Live, an interactive virtual version streaming on Looped. Reading Rainbow Live is preparing a special on on banned books, according to Burton.

What drives book banning?

“There is somewhere in there a desire to protect their children,” Burton acknowledged, “but protecting them from knowledge and protecting them from a real understanding of the world we live in is not good parenting.”

The comparison with the Red Scare in the ’50s doesn’t seem like an exaggeration to me anymore. That’s the time when FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and Senator Joe McCarthy teamed up to support bans of such books as Richard Wright’s Invisible Man, Henry David Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience (which, they said, encouraged men to protest American law and order), John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath (which focused on pain and tragedy, making workers blame the rich on the Depression) and Robin Hood (because he robbed from the rich and gave to the poor, encouraging Communism).

In addition to encouraging bans at home, in 1953 McCarthy sent two aides Roy Cohn (yes, the same Roy Cohn who inspired the character in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America and advised Donald Trump) and David Schine to search US Information Service Libraries in Europe and Asia for “subversive” books. Embassy libraries in Sydney, Tokyo, and Singapore even burned a few suspect books, prompting cartoonists of the day to compare such McCarthy-inspired censorship with the Nazi book burnings of 1933.

“I Too, Sing America,” by Langston Hughes

read by Denzel Washington

. . .

Among the subversive books singled out were ones by Ernest Hemingway, Mark Twain, Thomas Paine, Langston Hughes, Upton Sinclair, Lillian Hellman and Dashiell Hammett. Their books, McCarthy argued, were making the U.S. look bad and aiding Soviet propaganda against the West.

But it was the ban of references to Robin Hood in Indiana State textbooks that turned out to be the last straw for five students at the University of Indiana. After librarians across the country began to pull Robin Hood off their shelves, the students launched a unique protest against McCarthyism and his attack on freedom of speech – they donned the silly green hats topped with a feather worn by Robin Hood and his Merry Men and launched The Green Feather Movement. Soon Merry Men protests spread to other campuses (giving rise, some say, to the political activism of the ’60s).

Reading about those creative Merry Men protests got me thinking. What is the best way to combat this latest wave of book banning? Don a goofy hat like those Indiana students did to attract attention to the dangers of book banning and censorship? Perhaps.

But meanwhile, here are a few other creative ideas to consider. . .

Donate to Organizations

Filing Lawsuits Against Book Banning

PEN America (a writer’s advocacy group), Penguin Random House (the country’s largest publisher), five authors whose books have been challenged, and two Florida parents who have children in the state’s public elementary schools have filed a federal lawsuit to fight back against the book bans in Escambia County (which includes the city of Pensacola).

A single person in the county — an English teacher, no less — challenged more than 100 books for explicit sexual content and inappropriate language, including And Tango Makes Three, a picture book meant for elementary readers, about two male penguins at a zoo who adopt a baby penguin.

As a result of challenges, Escambia School District has removed or restricted more than 150 books.

The suit against the Escambia ban alleges that these recent bans and restricted access to books in school libraries by conservative teachers and parents have disproportionately affected books that address racism and LGBTQ relationships, therefore violating constitutional rights to free speech and equal protection under the law.

“I think the days of protesting in the streets are probably over,” Dr. Lindsay Durtschi, an optometrist who is one of the parents who joined this lawsuit, said on the Katie Phang Show on MSNBC. “The days for writing letters are done.”

The Florida Education Association, a teachers union, is suing Florida’s Department of Education, arguing that the department expanded the scope of the new law concerning books in schools by issuing training for school librarians this year that encourages them to “err on the side of caution” and remove books rather than fight to retain them.

File Complaints to Demonstrate

That Every Book, Including the Bible,

Is At Risk of Censorship Because of the

Ambiguous Language of the Recently

Enacted Florida House Bill 1467

To make a point that laws promoting book banning can backfire, Adam Graham and Brian Hawley, two former Pinellas County educators, filed a complaint with the Pinellas County schools against the presence of the Bible in school libraries, using the same criteria used to challenge dozens of other books lately in the county.

The Good Book should be banned, they argued, because like The Bluest Eye it contains sex and violence.

The two also complained about two other beloved texts – Syd Hoff’s Danny the Dinosaur, a book which has been used in classrooms since 1958, claiming it teaches “gender identity” (all its male characters wear pants and all its female characters wear dresses) and the 1997 picture book Four Famished Foxes and Fosdyke because it promotes the F-word.

Graham, a former English teacher at Pinellas Park High, and Hawley, who taught language arts at Largo Middle School, said they made the complaints actually to protect such books as the Bible by underscoring that they, too, could in turn be subject to censorship given the ambiguous language of House Bill 1467, the recent legislation signed into law by DeSantis that has encouraged the recent spate of book removals.

If these books can be realistically and intelligently challenged, they point out, then every book is at risk.

Make Banned Books Available

Free to Children and Teens at

Creative Outlets Outside the Schools

Columnist Stephanie Hayes, to combat her fatigue while Pinellas County was fighting over Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, began slipping copies of the novel into Little Free Libraries in Dunedin, Palm Harbor and Tarpon Springs.

When she reported on her “act of rebellion,” she received hundreds of emails and comments supporting her. “More than 120 letters so far, more than 400 TikTok comments,” she wrote. “One reader drove around looking for one of the copies I donated and sent a photo of her teenage daughter holding it.”

. . .

“Book banning goes against our core values,

and the issue is near and dear to our hearts.

You can see a few of the ways we’ve been

working to protect books from being banned here.”

– LittleFreeLibrary.org

A Banned Book Library has been set up in the lobby of American Stage at 163 3rd Street North in downtown St. Petersburg, thanks to Keep St. Pete Lit. The group’s founder, Maureen McDole, also created a gift registry for banned books at Tombolo Books.

Last month Adam Byrn Tritt, a high school educator in Brevard County and founder of Foundation 451, a free and inclusive library of challenged and banned books, held a pop-up giveaway at the Unitarian Universalists of Clearwater where young people were able to pick up two free books of their choosing. Children up to age 15 needed to be accompanied by a parent or guardian. Young people over 16 were invited to show up on their own.

Read Banned Books

and Encourage Lively Discussion

of Their Content with Others

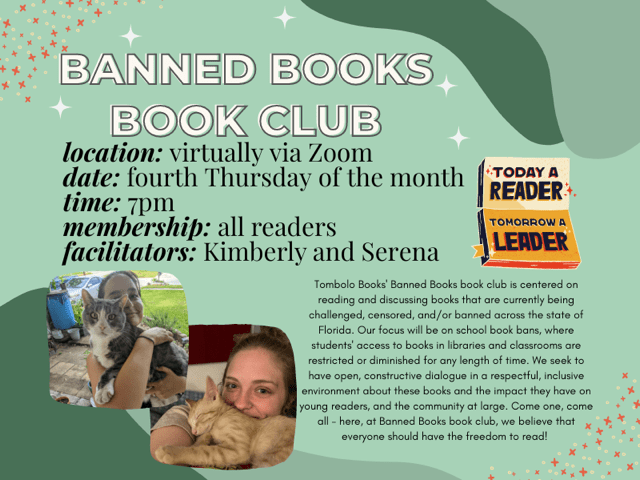

Tombolo Books’s Banned Books Book Club meets on the fourth Thursday of every other month at 7 pm via Zoom (next meet ups are on June 22, August 24 and October 26), hosted by Serena Utz and Kimberly Skukalek.

To receive email updates for this book club, you can sign up here. They have already read the young adult novel Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell and, of course, Morrison’s The Bluest Eye.