. . .

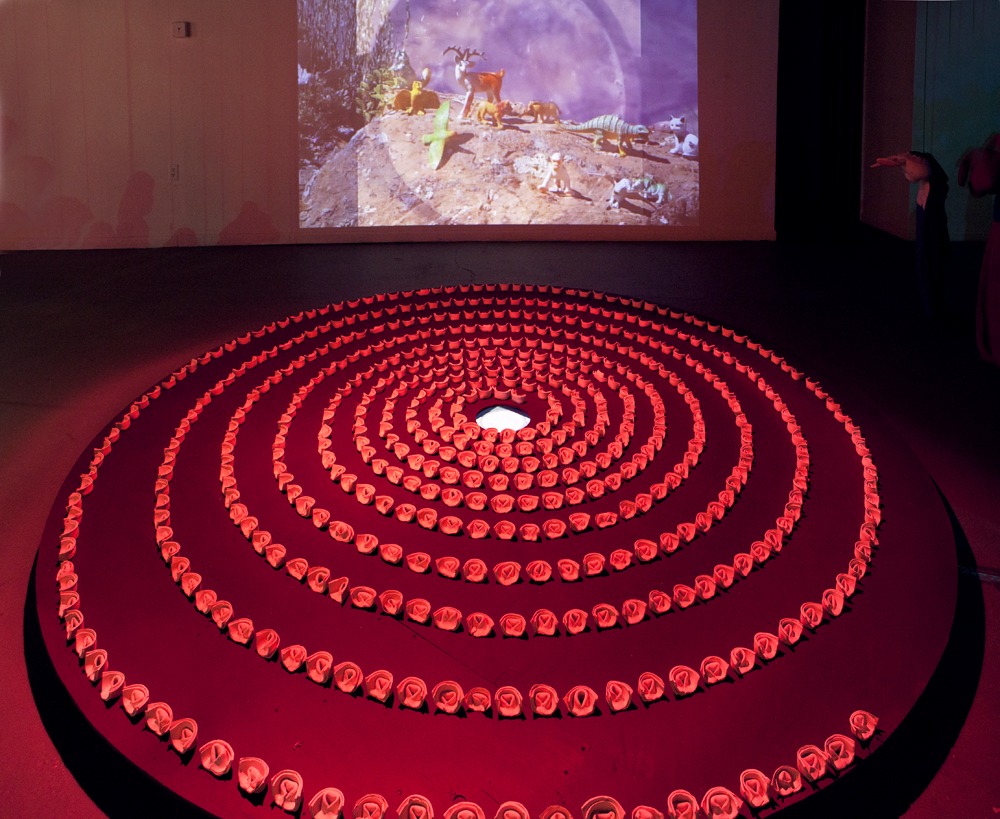

Abstract artist Kirk Ke Wang teaches at Eckerd College and his work is known internationally. His boldly abstract creations are colorful and striking – moving through painting, sculpture, photography, video, conceptual, performance and installation art.

. . .

“Although oscillating between them, I intend to weave a tapestry of my vision of the world, led by a consistent thread – the fear of inexorable cataclysm.” Still, Kirk Ke Wang’s work often appears joyous, as in his Human Skins series – a creative body of work that’s been exhibited at the Ringling Museum of Art, the Morean Arts Center, Lighthouse Art Center in Palm Beach, the Cobb Gallery at Eckerd College and currently at the Arts Center Sarasota in an exhibition running through November 27. Here is a review the Sarasota Magazine published last week.

You can watch Kirk explaining the process

of creating these collage paintings

made in part from clothing donated by immigrants here.

. . .

. . .

“I believe it’s the artists’ obligation to respond to our social surroundings. I call my abstract works ‘Social Abstract,’ a pun on the ‘Socialist Realism’ that I grew up with in China, as a critique to the ‘Zombie Formalism.’

“I enjoy playing visual games. . . What You See Is Not Always What You Get in art, as well as in life.”

. . .

You can hear Kirk Ke Wang share details of the inspiration and process behind his Sugar Bombs, Last Meal, Human Tide and Human Skins series, and his introduction to the arts in mainland China during the Cultural Revolution. Kirk and his sister were taught painting and calligraphy in a labor camp, without ink or paint but with many artists and arts professors whose work had been taken away from them. The children learned to play piano on a keyboard drawn on an old desk, with musicians singing the notes as the kids touched the imaginary keys.

. . .

. . .

From the recording. . .

“I grew up in a labor camp. That’s all my early memories. My mother was a pianist. My father was an engineer. He wanted to become a leader in municipal government, and that’s why he got in trouble and locked up in the labor camp.

“That is a dark age of Chinese history, the cultural revolution. For 10 years, colleges were closed. They locked up all the scholars, the professors in the labor camp. My sister and I, we’re the only two kids there. I was like five-years-old and my sister, she’s now Dean of Pace University, she’s two years older, but still very young.

“I had a great education in the labor camp, which actually made me who I am.”

. . .

. . .

The professors “still wanted to teach us even when there’s no paper, for writing calligraphy or painting. There’s a brush – no ink. So we used water. They saved the toilet paper – the old Chinese, yellowish-looking toilet paper, it looks like rice paper.

“So we use water, and they teach us how to write. And when it’s dry, we can reuse that paper, until it’s torn into nothing. So that’s how I learned my first art lessons.”

. . .

. . .

“And more interesting is music lessons. There’s no piano, even though my mom was a pianist. But they have great professors, they are trained, established musicians.

“So what they find is a piece of – not even a desk, the top of a desk. And they drew a keyboard on it, even with half-tones. That’s our first instrument.

“So we lay our fingers on it. They sing the sound. If you touch the wrong key, they sing the wrong tone. That’s how we learn.

“The other kids outside the prison camp, they didn’t have this privilege of learning music and art.”

. . .

You can explore the work of Kirk Ke Wang here

. . .

Arts In is produced by Sheila Cowley

Executive Producer, Barbara St. Clair

. . .