A Vivid, Vibrant Dance Career

and Still Moving Forward

. . .

You can listen to this conversation here

. . .

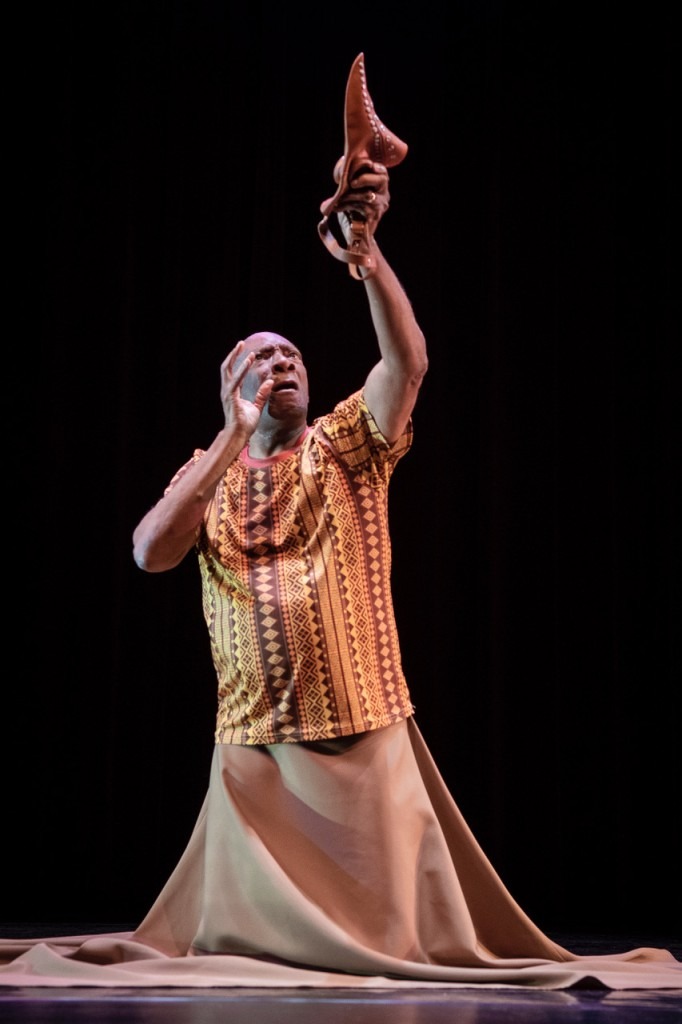

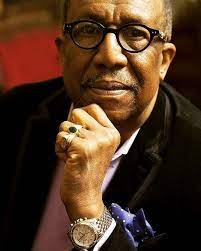

Dancer and educator John Parks worked with Alvin Ailey’s company, was in the original cast of The Wiz on Broadway and performed, taught and lectured across the country and in Europe, Africa and China. He’s now a professor at the University of South Florida School of Theatre and Dance, and works with veterans to create performances hosted by the Straz.

In a potent conversation ranging through his fascinating history, John talks with Barbara St. Clair about his experiences touring the South with the Jose Limón Company during segregation, the creative revolution of the 1960s and his own response with Movements Black Dance Repertory Theatre, how the early AIDS epidemic changed the Broadway we see today – and how he helped the undervalued dancers in the movie version of The Wiz go on strike for equal pay and credit. . . and win.

You can listen to this conversation on Soundcloud,

or read the complete transcript below.

. . .

usf.edu/arts/theatre-and-dance/john-parks

. . .

Arts In is produced by Sheila Cowley,

Executive Producer Barbara St. Clair

. . .

. . .

Transcript

. . .

John Parks: What happens when you see something and you spontaneously laugh or you break into applause or you jump to your feet? What effect did that have on your body?

Barbara St. Clair: Hello and welcome to Arts In, the podcast produced by Creative Pinellas. I’m Barbara St. Clair and I’m here with John Parks, who brings with him an amazing resume. John, you are a dancer, you are a choreographer, you are a teacher, you are a leader, you are a philosopher, I believe.

John Parks: Well, thank you. Thank you. I’m glad to be here.

Barbara St. Clair: You were in New York in the ’60s. What was happening in New York City and also throughout the country was really amazing and revolutionary. And one of the things that I noticed about myself as I’ve grown up is that I forgot how transformative those years were, how much creativity, a tremendous release of energy into our world. You were at the center of that.

John Parks: It was an exciting time, very exciting time. And it’s one that I really miss. Those were cherished years. For me, transformative is a good word because that’s what it really was in the dance community.

I’m saying the dance community, but it’s really more the arts community in general. There was a sense of collaboration and camaraderie and sharing of ideas that I haven’t seen since that time. You know, I would work with Archie Shepp or Duke Ellington or Sun Ra or painters like Romare Bearden and not to mention choreographers, but visual artists, Miriam Makeba. And the list goes on and on.

I mean, in terms of the civil rights – and I don’t know whether or not it was the civil rights movement or the Pan-Africanism or the Black consciousness – but there was a galvanization of ideas and of people, like-minded people that really kind of work together. I don’t want to just say that it was the Black community because it spanned a whole spectrum.

I remember the play Hair, you know – the Age of Aquarius, the Dawn of a New Age. This was so exciting in the arts community that this was new beginnings, Haight Ashbury in San Francisco, Woodstock, all of that was happening all at the same time. And it was very, very exciting. And we felt that we had we had agency and we had mission, and we made a difference. And we were free to experiment on what was happening.

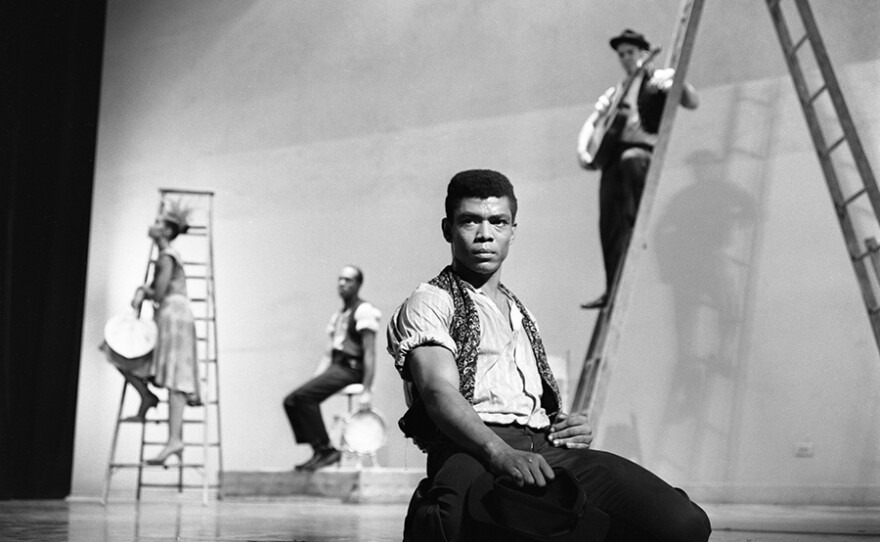

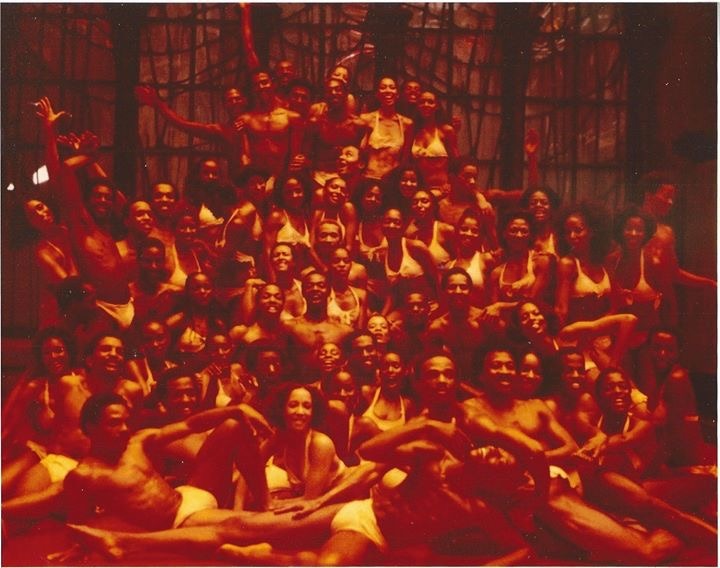

We questioned things and we pushed the envelope. But it was also for me – I had a dance company called Movements Black Dance Repertory Theater during that time and that dance company, we did all Afrocentric works. All the music, the costumes, the choreography, all dealt with people of the diaspora and the ideas of that. And so we were the soothsayers and prophets of the time, we reflected what was happening during that time.

I did a piece called The Man’s the Klan, and other works that dealt with what was happening in the streets and the political situation, what was happening in terms of Africa and South Africa and apartheid. I mean, all of those things were we commenting on. And the collaborations that we had were more specific in terms of raising money for the Black movement through arts. So that’s my connection with Duke Ellington, and I.S.121, Cooper Hall. All of those events were events to raise money for the people in the sit-in movement, the bus-in movement, to get the nonviolent students out of jail, to get the Panthers out of jail. Food to support the Panthers in their preschool and breakfast program.

One of the keys for me was that you’re using dance in other ways, other than performance. And that was something that kind of stuck with me, and I’ve been working towards ever since.

Barbara St. Clair: I think it’s so important to talk about that time and share the memories of that time, and the accomplishments of that time. I find in my sort of self an amnesia about that. And that amnesia limited my ability to think about what I could change and what was possible for the arts and what was possible for the arts in terms of society and helping people to think in new and different ways – and seeing what could be and really challenging the status quo.

John Parks: But do you know why? Do you know why that sense of amnesia was there?

Barbara St. Clair: I would love to talk about that. I would love to hear what you think.

John Parks: Well, I would say, number one, the assassination of Martin Luther King, the assassination of Bobby Kennedy. The assassination of Malcolm X. The police control and infiltration of the Black Panthers. All of those things and and many more had stopped us from thinking.

I know for me, stopped me from thinking about forward moving, and reflecting on the past because and AIDS and the AIDS epidemic, that robbed us of a generation and a half of everything – but mostly artists. So that the generation coming up, there was a gap there in terms of stepping on the shoulders of and learning from. There was that big gap of almost a generation and a half. What would happen, what would Broadway be if Michael Bennett and Michael Peters were alive?

Barbara St. Clair: Well, tell me, what would it be?

John Parks: I don’t know. Who knows? It wouldn’t be what it is now, because they were up and coming. They were coming with a new concept in terms of theater. Michael Peters choreographed a lot of the Michael Jackson videos. Michael Peters and Michael Bennett worked on A Chorus Line, so there was a void there – that’s how Andrew Lloyd Webber came in, because we didn’t have that creativity.

. . .

Because I thought about it. I mean, why am I silent? So we didn’t talk for 25 years. We didn’t say a word for 25 years. I’m talking about the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s – and ’90s, we started coming back.

Barbara St. Clair: I see that time now from today’s perspective as a promise, I sort of see that incredible output of creative product and creative process from the ’60s that we did lose the momentum for. And I think your point about AIDS and the assassinations, certainly the loss of a generation and a half of arts leaders. But what was done, what was accomplished, is a promise of what could be.

John Parks: Right.

. . .

Barbara St. Clair: So rather than an interruption, I’m feeling this energy of reconnecting with power. Artistic power, creative power, leadership power.

John Parks: All right. Yeah. No, I think you’re absolutely right. There’s been distance there, you know, and I think that it’s like when water finds its own level and it gets disrupted and it gets wavy, but after a while, when there is calm, it finds its own level. And I think that there’s a resurgence here. And I think that that power is there in terms of creative arts. I think it’s really happening.

And I think it’s happening in terms of art and its relationship with the community, which I feel is very healthy. I can see it happening in some things that I’m doing. I am working with the Straz Performing Arts Center in connection with Fred Johnson, who’s been working at the Straz for a number of years and was quite instrumental a number of years ago with the Community Arts Ensemble, where he would bring in non-artistic, just people off the street and work with them for six weeks. They would develop original play, original songs, written choreography and presented at the Straz.

. . .

World Rhythms and Song, Prescription for Healing

And these were people who, some had some experience in dance and some had no experience in dance, ages from nine months old to 70. And I had the opportunity to work with him for a number of years. And as a result of that, that’s how, from my point of view, the Patel Conservatory was funded, through his efforts in terms of that. And now he’s back and we have formed something called the Arts Legacy through Judy Lisi’s interest in developing and prolonging her legacy.

So we develop a performance or presentation group that performs outside of the Straz, on the grounds of the Straz. And we do a presentation once a month and it’s free of charge – that involves the community and community engagement and then watching live performances.

But the material that we do deals with the Native Americans or the Hispanic community or the Indian community or the African community or the Italian community. So each one of our performances deals with a certain subject matter that people are exposed to, little known facts that they may not be aware of. And and the participants of that are local community people.

. . .

I think that’s a way that we are kind of coupling and bringing the community together. I’m also doing something that’s called the Veterans Civilian Arts Ensemble. And this was an offshoot of Diavolo Architecture and Design Dance Company coming in and performing a number of years ago. It was a collaboration of veterans and civilians, and the idea was for them to work together.

The collaboration and the performance was so successful that they didn’t want to stop meeting. And now it’s the Veteran Civilian Arts Ensemble. So we’re bringing in painters. Bringing in vocalists, we’re bringing in sculptors, people who are writing. And so we’re meeting every other week. It’s a way to blend those two communities together. And so I see other things like that happening, and I think that’s very, very exciting.

Barbara St. Clair: In your biography, I think it said you started dancing when you were five and you said that most of the people who study dance are women. So as a man, a young man and a young Black man in in an environment that – I don’t know how welcoming it might have been for you as a young person coming into the dance world. But I would really like to hear how you got involved and what your path was to become a major dancer in a major company and then a choreographer and now a teacher.

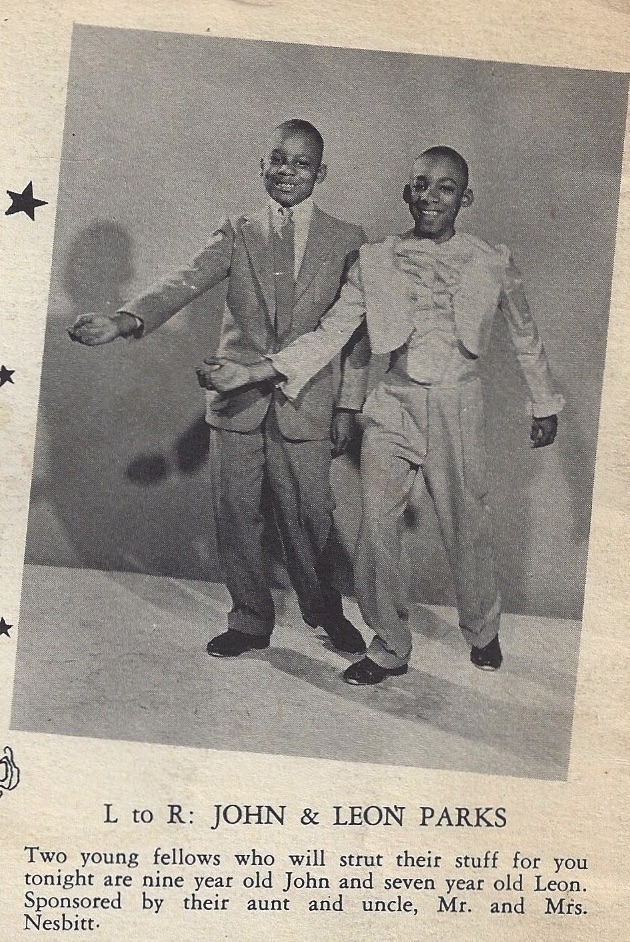

John Parks: Well, I did study. I started studying at five. Studied tap. And it was at a school called Mary Bruce School in Harlem. Mary Bruce was a woman that taught tap. And her sister had a studio in Chicago, Sadie Bruce. And the two of them opened dance studios.

. . .

Now, Mary and Sadie Bruce were supposed to have been, from what I understand, from my conversation with her, a relative of Bill Bojangles. And he was a big, big star. You know, in his day, he made more money than any other dancer on the planet.

And Mary Bruce said, Well, can you teach me? And he says, No, I am not going to teach you because they’re not gonna allow a Black dancer, a Black woman dancer, a female dancer, a shot. You know, number one, you’re Black. Number two, you are a woman. And during that time, all of those other dancers basically were men – hoofers. They were hoofers.

. . .

She did learn. He did throw out a few steps. And she was self-taught the way he was taught. There weren’t schools, you know, they weren’t places – and especially places for anyone of color. So she opened the school up and I studied there.

I can’t say it was great. I can’t say it was a great training school. I took ballet there and she did not know how to teach ballet – she was a hoofer. But we had our concerts at Carnegie Hall. You know, I can say at an early age, I performed at Carnegie Hall. And it was my entry into the dance community.

. . .

. . .

As a result of that, the Met was looking for Black dancers or Black kids for Aida. And so at the age of 12, I performed Aida at the Met. We did Aida, and we also did another Italian play, La Pettigo.

And we able to tour during that time, I think Washington and Philadelphia. Because during that time – it gives you some background of the times – Wednesday in New York City was a religious holiday. So in the afternoon, you were dismissed from your classes to worship the way that you wanted to. So if you wanted to go to Mass or you want to go to Temple, you want to go wherever you want to go. You could go and worship there Wednesday afternoons – and that was matinee time.

I didn’t miss any school at all because I would perform my matinees. That was my religion. And so I would do that. But yes. Yeah, you know, you are you’re anxious and you study and you you know that there is obstruction around and there’s resistance as you are growing up. But you you travel through time and space. You do travel and you do what you have to do. And unless it hits you directly, sometimes the racism, you’re not really aware of it too much. I mean, I am I was more aware of obstruction after it happened, than I was while it was happening.

under CC BY-SA 2.0.

I mean, there were things like – I went to Juilliard, but I also went to the High School of Performing Arts. And doing the summer, they would always give scholarships to people to study during the summer. I did not get any of those scholarships or those appointments, until I went to them and said, Well, you know, you’re giving this out to everyone else. There wasn’t that many men in the department, so all the guys had gotten scholarships as an incentive to keep on dancing. But I had to ask for that.

You know, you do that and you just go on. It’s interesting. As a person of color raised in this country, a lot of things are assumed. You kind of look at it from the outside. You say, well, why did that happen? Why did this happen? Why did that happen? But if you grow up as a as a Black male in this environment, you are indoctrinated to it. You are a part of it and you assume certain things.

Like, for instance, we talk about the talk that every Black boy has in terms of what to do when you’re stopped by police. Don’t do that. Don’t do this. But that conversation is inbred in you. You don’t know why, necessarily, why that is – or if you do, it’s part of your culture. And so you kind of adapt to it, you know, which is a real sad thing. I feel it’s a real sad thing.

But those kinds of things happen. I’ll give you an example of what I’m talking about. You’re driving a car and you come up to a red light. There is a person with a homeless sign, a Black person with a homeless sign on the curb. They might start walking towards your car.

Me, I think of myself as being conscious, you know, racially conscious and an Afrocentric person who has lived through a lot of stuff. What do I do? I look and see if my door is locked, right? So if I do that from an automatic point of view, then I would say most of the people on this planet would do the same thing, or most people in the United States would do the same thing. We’re conditioned. It’s like being brainwashed. It’s hard to dispel that.

. . .

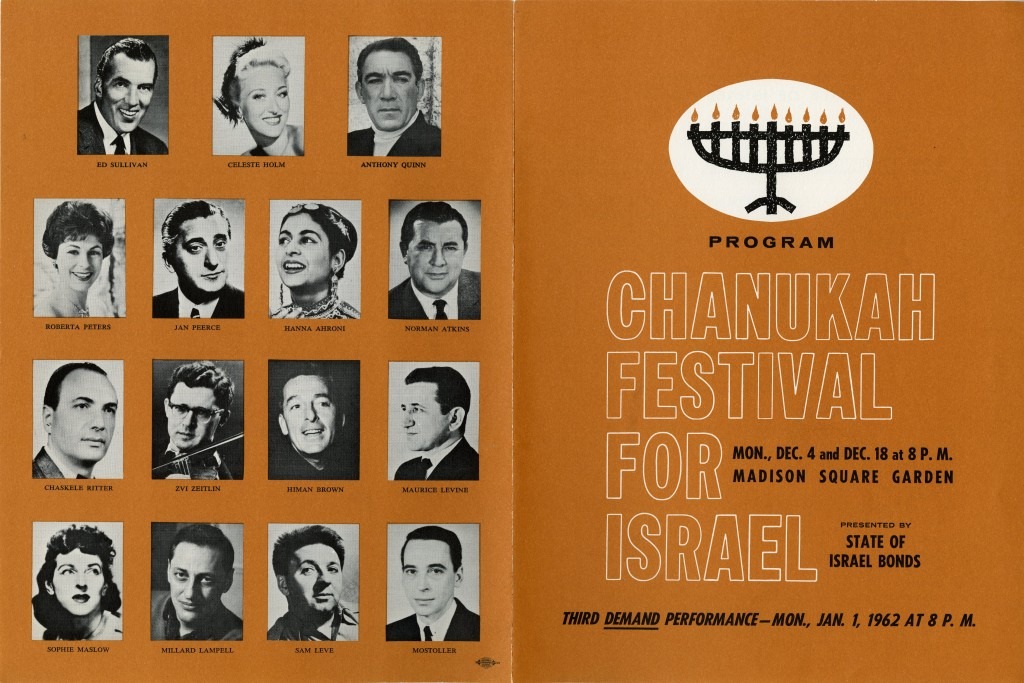

And so when you ask me, what was it like? In retrospect, it wasn’t healthy during that time. You did what you could and you took what you could. You know, my first experiences with dance companies were in all white dance companies. I was the first person of color in the Limón Company. I was at one point the only person of color in the Anna Sokolow company. I mean, I’ve worked with Mary Anthony, Ruth Currier. You know, I did Hanukkah festivals. I mean, I worked with a lot of white companies and was the only one in those companies.

. . .

. . .

You know, the dance community is a lot more liberal than the rest of the environment, you know what I mean? Where you are judged primarily on your ability. Not to say there wasn’t racism there. There was. But it didn’t reflect the same degree in the same way as the rest of the United States. And also you’re in New York City. I danced with Olatunji’s Company, West African dance company. And we actually did some work for the World’s Fair 1968.

Barbara St. Clair: Wait, was that the one in New York City? I was at that one.

John Parks: You were?

Barbara St. Clair: I was.

. . .

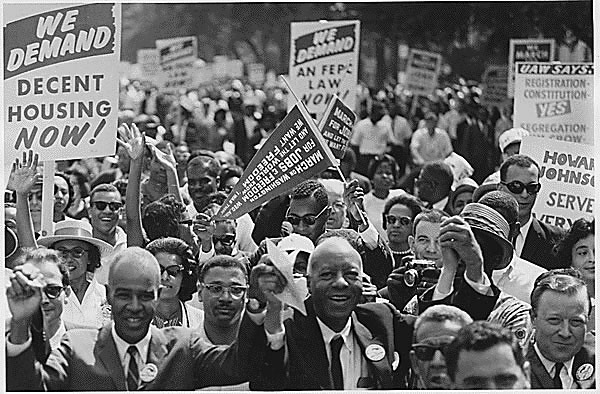

John Parks: I danced there for a while, but I was in the Limón company. I toured with Jose in the ’60s, in 1962, touring the South with a bus and truck – one night stands. You arrive in town that day. Check into your hotel. You try to scramble around to get something to eat and do whatever you need to do, get your shoes shined, get a haircut or whatever you have to do before you go to the theater, to space and work on lighting and get ready for the performance.

That night you perform, you go either to a reception then you try to go out to eat, you go back to the hotel, go to bed. Next day you get on the bus, go to the next spot. One night stands. We did that. You know, some of them were two nights and some of them were three nights. But basically it was a one night stand of touring the South, and we were on buses. We were on a bus with New York State license plates, a company of 32 dancers. And I’m the only African American.

Barbara St. Clair: Wow.

John Parks: So when we got to places, they thought we were agitators from the north. Number one.

Barbara St. Clair: You were just a different kind of agitator.

John Parks: Number two, they thought that we were civil rights activists and we were part of the the bus sit-ins, the cafeteria bus sit-ins. So they didn’t get too much flack. But I got a lot of flak. I had guns pulled on me. My life was threatened. When I went into, whether it was a restaurant or store, the proprietor of the store walked out along with all of the customers. Because during that time there was a stipulation that you can’t really say that you can’t serve anybody, you know. But they would say that they could serve me if I walked in with some of my dancers, some of the dancers – they could serve me, but they couldn’t serve anyone else.

Barbara St. Clair: Oh, geez.

. . .

John Parks: So, I mean, that was a wakeup call for me. So that was a reality of all that I had not been exposed to during my time in New York City. Certainly Emmett Till and the death of Emmett Till in 1950-something was a traumatic change for me. My mother, who is from the South, did not even want me to go down there. She said she was afraid that, because I would be like Emmett Till.

I’m born and raised in New York City, you know what I mean? I’m footloose, fancy free, you know? And so I didn’t have all of those sensibilities of what to do, what not to do in the South. I knew what to do and what not to do in the North. So that was what I was dealing with racially.

. . .

Barbara St. Clair: How did you connect with the Alvin Ailey Company?

John Parks: Well, I was working with Donnie McKayle, you know, during that time. You can work with a number of different companies at the same time because you probably only have one performance. And the way that the choreographers worked, they work for long periods of time developing the work. It was an arduous task. You did your research. You studied the characters. You worked on the pieces. Pieces were not just thrown together. So it took time and choreographers and dance companies, they embraced the fact that they couldn’t support you, except for maybe the performance. So because the work was so slow in being developed, you can step away and you can come back. So people would work with a number of different companies at the same time.

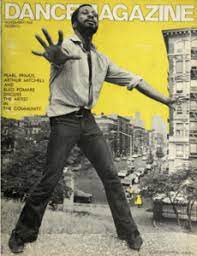

So I was working with Anna Sokolow, and this was all in one facility. This was at Clark Center. I was working with Anna Sokolow. I was working with Eleo Pomare and Rod Rodgers. And the Ailey company did not have their facility. They were also working in the same building. And Clark Center would say, we’d give you rehearsal time if you would just do a performance. So all four companies would be rehearsing at the same time, in four different studios.

Barbara St. Clair: Oh, that must have been fun.

. . .

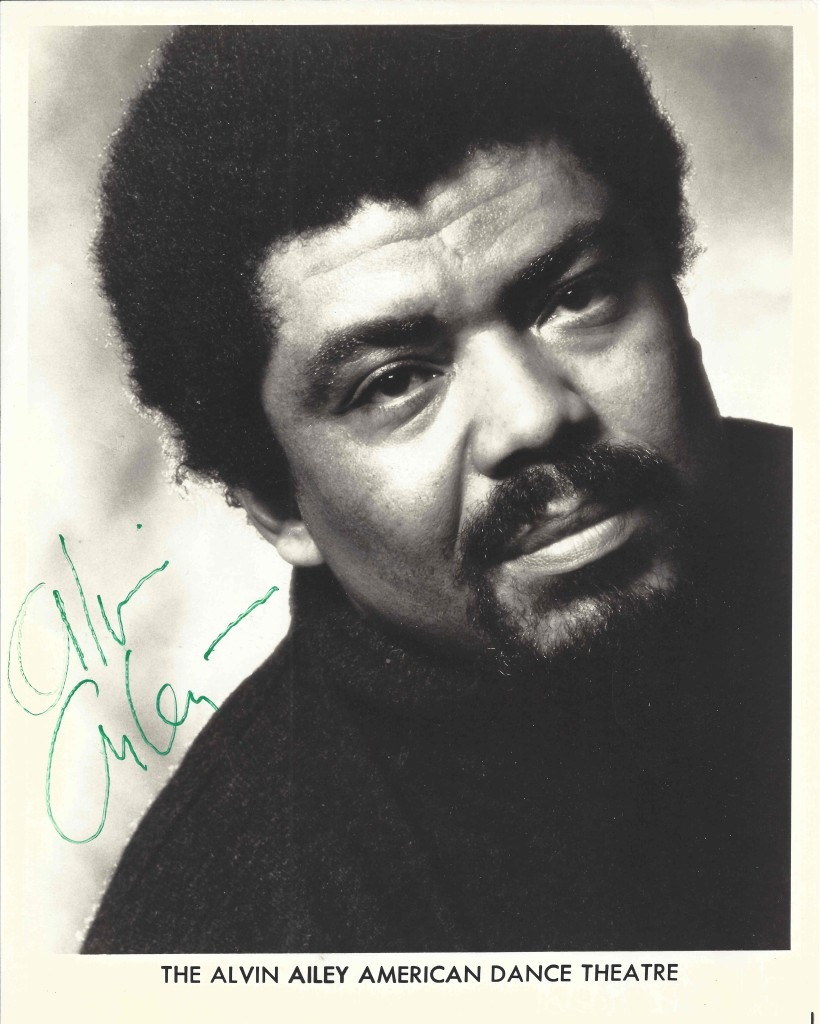

John Parks: It was beautiful, it was really beautiful. And so we did the performance. And Ailey asked me to join the company. He saw me dance in three of the other companies’ works, you know. And so I, I declined.

Barbara St. Clair: Oh!

John Parks: I told him that all of your dancers are soloists. Dudley Williams, Bill Louther, Clive Thompson. All were soloists with the Graham Company. Carmen de Lavallade. I mean, they were all soloists. They were principal dancers in other companies.

I said to him, I said, when I join this company. I don’t want to be delegated. I want to be like them. I want to be able to contribute, you know. And he says, well, you will. That’s why I’m asking you. I said, No, but I don’t feel – I need to learn a few things. I need to learn a few things. So I declined.

And about a couple of years later I saw that he was having an audition because he said, Well, when you’re ready, just give me a call.

Barbara St. Clair: You get that in your pocket.

John Parks: Right? Yeah. This is a get out of jail free card. But I saw he had an audition. And so I didn’t call. I went to the audition. And the reason why I went to the audition, I wanted to see for myself how I fared with other people who were auditioning. Then I knew that that would be a right fit for me. And I was accepted and I joined the company.

And you know how you have to put your resume for the program? You have to do a resume for the program. So I gave him my resume. And we are in rehearsal on the East Side on 59th Street. And he stops rehearsal, reads my resume and signs his name at the bottom, saying, I’m honored to be among the people that you have worked with.

Barbara St. Clair: Wow.

John Parks: Well, I – you know, I’m getting chills every time every time I say this story. I was, you know, I was floored. I was really floored. But I mean, that’s the kind of humanity and honesty and humility that that man had.

It didn’t serve me right with the rest of the cast. The rest of the company started looking at me, Who is this guy? You know, this is the new guy. So I ran into a little static with that. But I was was in good stay with Alvin.

It was a good experience. Those were some wonderful artists, just wonderful artists that were so giving. And all of them were so, so special. I mean, I have been in other companies, but to work with a group of artists that were so eclectic in what they did – you know, we would do John Butler’s work and then we would change and do Talley Beatty‘s work.

. . .

John Butler was a ballet choreographer, very much like Glen Tetley. He wasn’t a classical choreographer. He was a contemporary choreographer of the day. Talley Beatty used to dance with Katherine Dunham‘s company. He is actually touted to be creator of modern jazz technique. Stack Up, Alvin Ailey’s Stack Up or Come and Get the Beauty of it Hot or Tocatta – that choreography is Talley Beatty.

. . .

Barbara St. Clair: Just a lot of different approaches.

John Parks: From jazz to ballet to Haitian, West African. Those dancers could do it all. Yeah, they could do it all and not just do it. They could do it, you know? And it was just amazing. I mean, just amazing. You know, you had Sarah Yarborough and Miguel Godreau, Morton Winston, who were dancers with Harkness Ballet – just incredible dancers.

Barbara St. Clair: It was really something going on there, wasn’t there?

John Parks: You know, it was an interesting time. And Alvin, in terms of the works that he was doing, they were really to kind of identify the Black experience – although he dealt with humanity in a way that reflected everyone’s experience.

I mean, when you think of Revelations, it certainly, it deals with the Black experience, but it is humanity and it’s universal. That’s why it’s a classic, because it has withstood the test of time and it can affect everyone. That and Blues Suite and other works that he’s done. So that is where he was coming from. In terms of his works. Which I didn’t always agree with – I thought that he could be a lot more radical than he was. But I have since seen the error in my ways.

. . .

Barbara St. Clair: Well, you’ve changed and you have a different – you bring different things now. But I think that’s part of why you went ahead with the Movements Black Dance Group, right?

John Parks: Yeah. Well, that was that was actually before I joined the company. I was already indoctrinated. I joined the Ailey company in 1970. And Movements Black was, I think, in 1967, ’68. So I left my own company to join this company.

Barbara St. Clair: That’s a pretty strong statement.

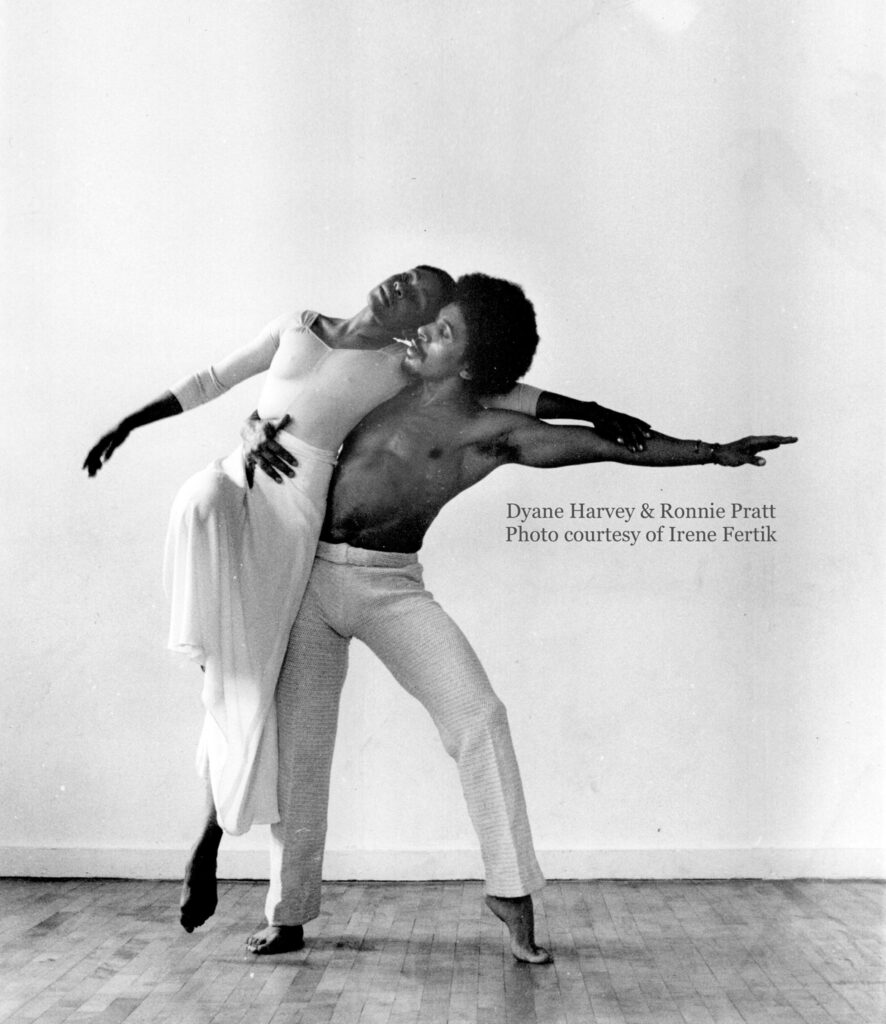

John Parks: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, it wasn’t just my company, I shouldn’t say that. There were five corporate members. There was Ronald Pratt, Judi Dearing, Miriam Greaves. Chuck Davis was a member of it as well, and myself.

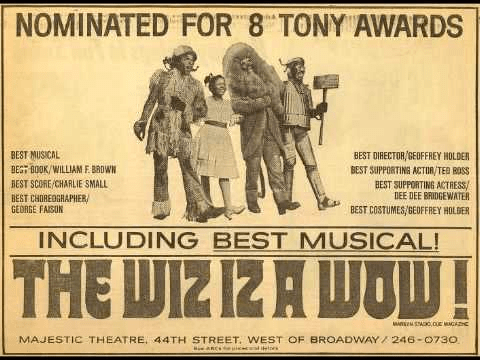

Most of my work had been concert work in dance and George Faison had asked me to come in to work on The Wiz. And I started out as his assistant to the choreographer and then became a Swing Dancer and Dance Captain. And it was interesting. It was interesting.

I was just telling someone recently that I gained a respect for Broadway and musical theater that I had not known before, had not experienced before, coming from concert work. You know, we were so studious in what we were doing and and tunnel-minded and we were focused in. And I had no idea that that same attention to detail was also – and more – was experienced in the Broadway theater element, where you would have dancers and singers and actors working together collaboratively.

. . .

We always imperceptibly are working towards, I think, towards what we’re going to do. And a lot of what I have done have been maybe eclectic, but it’s been on a path of inquiry.

So doing a Broadway show was a unique experience in terms of coming off – with Ailey, he would do Revelations almost every performance. You had a repertoire of 15 pieces, by the time I ended 2020 pieces, you know, and Revelations would be one piece, but you would have maybe five sections in that, that you would dance, you know. So it was a lot of different works.

And doing The Wiz, you had one show – eight performances of one show. How do you make it exciting for the audience, and for yourself? How do you keep it alive? Because if you don’t keep it alive, once it becomes boring, people are not going to come, right? It’s not going to be profitable. It’s not going to be good for you. How do you keep it alive? And you don’t want to be onstage and just run through it, you know, go through it. From a from a modern dance point of view, that’s not how we roll.

Most of the company – most of the dance company – mostly all of the dancers came from a modern dance background. George came from a modern dance background as a choreographer. And so that’s how we fashioned this show.

. . .

It was very exciting, very exciting to be able to kind of, in a sense, settle down, be in New York, be with my family, and do a show that was kind of revolutionary.

Prior to that time, people weren’t going to the theater. Broadway was dying. The Wiz helped revitalize Broadway, number one. It brought a clientele in that normally would not necessarily go to see a show – but a Black community, a Black church community in – the works that were on Broadway didn’t represent them.

In addition to that, it was a revival. And it was well, well done. It was exciting.

The choreography was exciting. It was a dance show. Fosse, he had done dance shows before, but this was a dancer’s show. The songs were great. It won seven Tony Awards. And so it was of that kind of caliber. And it wasn’t the accolades that I admire, it was the work that was so excellent that I really admired. And it was good financially. I bought I bought my brownstone from from doing that show. And it was the beginning of revivals.

Barbara St. Clair: I mean, that was really an important show. And I love the fact that you were well compensated, you know, that you could make a good living doing that, too. Because of course, that is a very major issue for artists in this community right now, is how you how you have financial well-being and do your art.

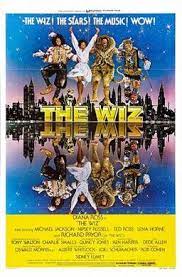

John Parks: You know, I was asked to do the Wiz film that Louis Johnson had choreographed. The film had Diana Ross in it and Michael Jackson and the usual suspects. And when I came in to do it, I realized that the dancers were being paid day to day workers. So in other ways, during that time as a day player, you would get paid $66 a day. Although the dancers were required to sign contracts for the duration of the rehearsal and the film.

I joined the rehearsal process kind of like late in the game because I had other – I was doing a one man show and I toured the United States in Europe doing a one man show with Affiliate Artists program. And so when I realized that with 66 dollars a day, I told Louis, I said, Louis, I can’t I can’t afford to do this. I got other contracts that I have to fulfill. When I’m finished with those contracts, then I can join the rehearsals. And so I came in late in the show.

Then I found out that the models were negotiating their contracts, and they were top models. They were top European models and American models. Needless to say, this was an all Black show. Right? And I talked about the Broadway being a dancer’s show. The film was also a dancer’s show. And so he had hired over a hundred dancers from the United States and Europe. All Black dancers are working. It depleted Arthur Mitchell‘s company. So all of Arthur Mitchell’s company was in The Wiz, along with alumni of Ailey’s company and whatnot.

The show had already basically been rehearsed and was ready to be filmed. So I organized. To strike. And I got signatures by all of the dancers, all of the principal actors – Mabel Robinson, Michael Jackson, Ted Ross, Pepsi, everybody except Diana Ross. And we struck for contracts so we can get paid the same as actors.

Now the reason why Diana Ross did not sign was because the work was being produced by Barry Gordy and Motown. And she was starring in the show. And so she had a vested interest in it.

But we negotiated and changed our contracts to – and I don’t remember what it was, pink or white or white or pink – but from whatever contract they had to another one, that was basically an actor’s contract, it was similar to an actor’s contract, which meant that the dancers would get retroactive pay.

Barbara St. Clair: Wow.

John Parks: They would get hazard pay. They would get – they would be recognized. So in other words, you know, when you do a film, when your face is recognized for a number of seconds, you get upgraded. If you have dialog, after a number of words, you get upgraded. So all of these dancers that were getting $66 a day were now getting upgraded because of the work that Louis had them do. In the show, like the Crows, for instance, they had dialog. They were featured along with Michael Jackson. They got a tremendous boost in salary.

. . .

I got pretty much nothing out of it because I joined it last, but we were able to get that, in the contract. And not only that, I negotiated to get representation for the Screen Actors Guild, Black representation in the Screen Actors Guild in front of and in back of the camera, and put a dance representative Cleo Quipman in that position, to monitor any other shows, any of the musicals that come up, that representation was there.

So we got royalties where normally we wouldn’t get royalties. And we get our credit in the title. And so I just want to mention that because I think it’s significant as an advocate for dance, what we fight for in terms of our own rights.

Barbara St. Clair: It’s a hero’s story. I mean, we all want to be change makers, right?

John Parks: Yeah. Mm hmm.

Barbara St. Clair: That’s a very concrete change.

John Parks: Yeah. Yeah. I feel real good about that. You know, I mean, it just wasn’t me, but I was part of it, you know? Yeah, I feel. I feel good about that, too. Kind of turn some things around, some inequities. And if you do something about it, you know, then, you know, God bless you.

Barbara St. Clair: Your moment was perfect because all the rehearsals are done. They’re all ready to shoot. You had leverage and you went for it.

John Parks: So Sidney Lumet brought me into the trailer and said, You will never, ever work in film again.

That’s fine with me. I did two other films since that time.

Barbara St. Clair: I was sort of jealous, you know, but also in, I guess, that much creativity and that much sense of possibility and the ability to impact. I was looking at a statement about the Movements Black, and you wrote “Dance is a barometer of the times.”

That is true for many art forms and many artists. But because dance is storytelling in the moment, that feels very, very true. And then I would want to bring us back to the present. If dance is a barometer of the times, what is the barometer saying to us now and how is it expressing itself?

John Parks: Hmm. Interesting question. Interesting question. I hesitate. I’m hesitating in a way, because I tell my students, this is your time. Yes, this is your time. I did some heavy lifting doing my time. I’m offering you possibilities and opening the vistas for you. I can’t tell you what to do. You have your finger on the pulse of what’s happening, you know, and quite frankly, I could venture an opinion. But, you know, Gibran has – in The Prophet, in the book The Prophet, he has a phrase when he talks about children, that the children are from you, but not of you. They have their own voice. They have their own time. They live in the present. They live in the future. You give them both and you give them access.

So it’s hard for me to say. And I don’t really want to venture. I mean, I love answering your question, but I don’t know Twitter. I don’t know social media. I go to email kicking and screaming, you know. And so, that’s why a lot of my choreography is reflective at this point, a lot of my teaching. Although I might teach a codified technique, I teach it in a way that opens up areas for them so that they’re not bound by – by convention.

. . .

Barbara St. Clair: So what really struck me and it’s giving me those little goose bumps, is that was your journey as a young dancer. You were in this certain place, New York City, at a certain time of the ’60s, where the creativity – almost like pent up creativity – was explosive. And that was your journey. But you’re sort of offering your students the idea that this is their time.

John Parks: Exactly. Exactly. And, you know, a lot of my focus at this particular time in my life is using dance as a healing modality. Using the therapeutic elements of dance, of theater.

An audience goes into a theater and they come from all different walks of life, all different experiences. They might rush to the theater, or whatever they’re going to see. And they are talking with each other or they’re reading programs or whatever. And the lights go down, the curtain comes up. There is a shared experience that happens where they are focusing in on what’s in front of them.

When they leave that theater, they are different than when they walked in. Yes, that’s exciting to me. That inquiry into what happens to the body as an audience member – what is the dopamine, what happens to the brain, what happens to the physiology in terms of that experience? What happens to the performer performing, now that the scientific community recognizes that the arts and dance is a tool for healing? How do we assess that? How do we evaluate that?

So part of what I’m doing with Johns Hopkins is working with them in a way to help define that. The Peabody Institute is working on a degree program so that dancers after they graduate can go into hospitals, go into therapy – not as dance therapy, but as dancers with those skills to help physical ailments, emotional ailments through movement. And so that’s where my focus is now.

. . .

I’m also teaching a course at Valencia that’s called Movement and Health. The course is dealing with breathing, the course is dealing with yoga, the course is dealing with meditation, dealing with movement. I mean, a lot of the Graham exercises, the floor exercises are meditative movement. Louis Schweygard’s corrective rests, or courses that I had at Juilliard, work very well for dancers, non dancers – but using dance as that tool. And what other ways can dance be beneficial in healing and wellness for others?

Barbara St. Clair: You did mention John Hopkins and you are involved with them in the International Arts in Mind Lab of the Brain Science Institute at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. So what are they trying to learn there?

John Parks: Well, they’re trying to learn what happens to the body when you are exposed specifically to dance. And to assess with that, if you were able to take someone’s blood pressure or their heartbeat as they watch dance and see what was stimulated, how different movements affected the body in different ways. We know this as dancers because we know how that communicates. But, you know, a way to assess it and a way to document it and to analyze it has not been done before.

I mean, what happens when when you see something and you spontaneously laugh or you break into applause or you jump to your feet? What? What? What did you see? What was that? What did it – what effect did that have on your body? What caused that visceral reaction to you? So it’s interesting. It’s very interesting.

Barbara St. Clair: I wanted to ask you, since you are connected with young people as a faculty member at the university. What are young people thinking and saying about the field of dance and about what’s going on in the world and how they might want to express their thoughts about it as artists?

John Parks: I mean, it’s very refreshing because they come in with the concept of ballet companies and modern companies and, well, competition. And it takes about a year for them, but then they cleanse their mind so that they can think and open their perspectives in other ways.

But they are quite exciting in terms of the things that they are coming up with – in terms of using their degree in alternative ways. There’s a big push. A lot of my students are into health and wellness. It’s a little bit more than just going into physical therapy or massage therapy, but they’re really interested in using dance as a healing modality, which I find very refreshing. And to recognizing the skills that one has as you’re trained in dance and using that in other ways.

We have attention to detail. We have a good work ethic. We have a lot of stamina, a lot of endurance as dancers, and we can recognize body language. And those are all good qualities as a performer in the arts, but also attributes that can be used in other fields as well.

I find that some of the students, as they graduate, they go into arts administration and they fit in right there. We do have a number of that have formed companies and that are with major dance companies. I mean, there is the whole spectrum.

. . .

As you know, most of the students who study dance in elementary, junior high, high or college are women. And not all of them are going to be in dance companies or work professionally. And us as a university, we recognize that realism and try to train them in a way or educate them in a way where there are more options. They have more options.

Yes, the performing element, taking technique classes, is always going to be there. But for them to study kinesiology, for them to study movement analysis, for them to study dance history, for them to be involved in dance administration or anthropology or some of the other sciences is is open to them. And those skills are not lost in those professions.

I mean, I just remember years ago where a friend of mine who was a professional dancer in New York and there wasn’t that much work. And you know, there isn’t a lot of work if you’re working as a freelance dancer, you’re not really working a lot. But she was a nurse and she got her degree and she became a doctor. But she still was a dancer and she still danced when she could. As a matter of fact, her profession as a doctor supported her dance career.

And so, you know, we talk back in the day, well, you can wait tables and this and that. No – you can have four or five different careers.

I always say that I would like to teach a student that is the first student to choreograph something in weightlessness.

Barbara St. Clair: Oh!

John Parks: With non-gravity.

. . .

Barbara St. Clair: Thank you so much, John, for being here today. This has been a wonderful conversation and I have been talking to John Parks, a professor at the University of South Florida, a choreographer, a dancer, a producer, a director and a leader for the dance community, and now moving into dance and health and well-being. Thank you so much, John, for this great conversation.

John Parks: My pleasure. It was a delight talking with you. Thank you very much.

Barbara St. Clair: I’m Barbara St. Clair and you’ve been listening to Arts In, the Creative Pinellas podcast. Sponsored in part by the Pinellas County Board of County Commissioners, Visit St Petersburg, Clearwater. The State of Florida, Department of Cultural Affairs and the National Endowment for the Arts. Our show is produced by Sheila Cowley. It’s easy to subscribe on your favorite podcast service if you enjoy this program, we hope you’ll share it with a friend. You can find more conversations with visual, literary and performing artists at CreativePinellas.org. Thank you for listening.