. . .

Walking through the front door of Marie and Rusty Hammer’s house is like falling out of the wardrobe in The Chronicles of Narnia into a magical world of artistic imagination.

Even before you cross the threshold, you get a hint of what awaits you. At the front door, I am greeted by a bear who looks like he is delivering the mail. A strange dog in the front picture window waves at me.

“We aren’t in Kansas anymore, Toto,” I whisper to myself, as I leave the neighborhood of ordinary houses lining a street in west St. Petersburg behind me and am ushered by visual artists Rusty and Marie into their wonderland of a home.

That bear at the door, I soon learn, was painted by Marie who also painted two even larger (and equally friendly) bears on the foyer wall. Why bears? “I just like bears,” she says. Marie currently specializes in wooden wall sculptures — faces of lions, horses, rhinoceros and human — made from scraps of oak, dry branches and driftwood.

The dog in the window is Rusty’s creation. He calls him Bow to the Wow. Rusty is known for his whimsical canine assemblages that have equally playful names – the female Trophy Woof, King Pup in an Egyptian headdress, Queen of Barks, Day of the Dead Dog and Fiddler on the Woof.

Everywhere I look in the Hammers’ house, I am treated to a burst of creativity. Marie’s paintings of reindeers leap across the back of dining chairs. On the wall I spot an abstract painting of reds, blues, yellows, purples and greens. “It’s called Crocodile in the Nile,” says Marie. “I’ve never been to Egypt but when I finished the painting, I saw a pyramid and crocodile tears.”

When the Hammers first got together, Rusty began rearranging Marie’s furniture — several times. “I liked it. It looked better,” says Marie. When she needed a lamp, Rusty made her one — a mermaid with a cooling system CPU computer on its head. Now he has arranged their house as its own work of art.

His dog sculptures pop up all over their living room. A dog made of tiny pieces of glass, a dog in the shape of a bench, a dog holding up a lamp and a dog made up of Mardi Gras beads playing a beaded drum that says Bone Temps Rouler.

A bird-shaped whistle they found in Denmark sits on the snout of another dog who has clocks for ears and holds the old-fashioned red clock they found in the house’s kitchen when they moved in. Rusty calls him Cuckoo.

While the rest of us may collect shells and throw them into a box, Rusty built a series of long narrow glass shelves — or ‘shellves’ as the pun-loving Rusty might spell it — for his collection, lining the shells up in ascending order of size to create an artful wall display.

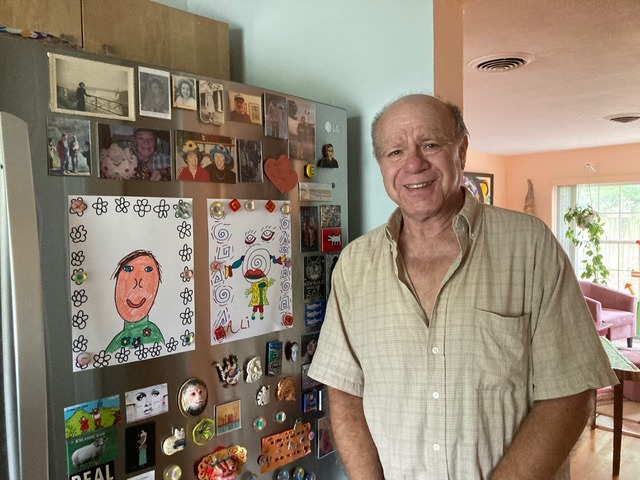

Even the Hammers’ refrigerator is graced with artwork — portraits by artists from Creative Clay, a St. Petersburg arts center for people with disabilities, who go only by their first names. Grace has drawn Marie, capturing perfectly her sweet smile and kind eyes. Ali’s more abstract portrait of Rusty has caught his peripatetic spirit.

“Creative Clay is one of our favorite places,” says Marie. “When we go there, the people and the art always make us smile.”

This week the Hammers are holding a fundraiser for Creative Clay. Rusty’s dog sculptures and Marie’s wooden faces will be on display on the covered back porch at Creative Clay at 1846 1st Avenue South for Second Saturday ArtWalk on November 11 from 5 to 9 pm. All proceeds from their sales will be donated to Creative Clay.

The Hammers know something about making people smile. Rusty made his first quirky dog by mistake, he tells me. “They didn’t start out being dogs.” He just had a lot of lumber left over from the Center for Art Lovers float he helped build for a University of Florida parade in Gainesville where the Hammers were living at the time.

Rudy called his first dog a Dog-a-saurus. He went on to make Barkson Pollack (full of splatters) and Salvador Doggie (with a mustache).

The “Center for Art Lovers,” by the way, never existed. It was an invention by Rusty to convince a group of Gainesville artists, including his wife, to produce football-themed paintings for that float. His friend Lennie Kesl painted footballer Tim Tebow. Marie did a portrait of Albert the Alligator, the UF mascot.

Also contributing was Fred “Rootman” Woods (who now lives in St. Petersburg). “Lennie was the only one who had to sit down on the float,” Rudy remembers. Kesl, a beloved Gainesville artist, died in 2012 at the age of 86.

After living 25 years in Gainesville, the Hammers decided to move to the Tampa Bay Area. Rusty’s parents had lived in Coquina Key in St. Petersburg, so they knew the area well. They first moved into a Town Shores condo in Gulfport. But they soon realized they needed a house with a workshop for Rusty, more space for all their artwork and a garden.

The Hammers met in a Pennsylvania garden, introduced by a friend. Marie is from Philly, Rusty from Massachusetts. Their first date was at a Phillies game. Marie was doing commercial art at the time, soft sculptures. She was also promoting rock and roll.

Although Marie’s mother and grandmother were both artists — their painted ceramic lamps are displayed in the bedroom — and Marie had gone to art school in photography, she didn’t start to seriously paint until after she met Rusty who recognized her talent and urged her to pick up a brush.

The first thing that Marie painted were those old straight-back chairs that Rusty had inherited from his grandmother. Marie soon graduated to canvases — large paintings of horses, often in multiple colors, and smaller portraits of her cats. Once when she didn’t feel like painting, Rusty told her to “just paint what you feel.”

She started a painting with slashes of the bold colors she favored. “I liked it but it wasn’t enough.” Suddenly she had an idea and before she knew it a black panther entered the canvas, slithering across her abstract background.

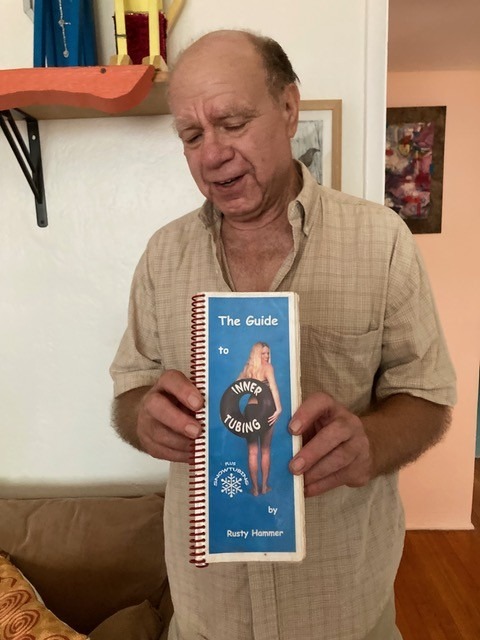

Rusty doesn’t consider himself an artist. “A folk artist, maybe.” He has worked in the arts, however, all his life. He was event co-ordinator for the Richmond Arts County and also worked for the symphony there.

Music has been part of his life since he started on the piano in the third grade. “Yeah, my mother was one of those.” In 4th grade he moved on to the clarinet and in 4th grade the violin. “I hated practicing,” he admits.

He ended up playing the tuba, participating in children’s concerts in Richmond to benefit UNICEF. He still loves playing the tuba, most recently for the South Pasadena Community Band.

As we tour the living room, I spot a side table, topped by a box laid on its side with an open end facing outward. Inside dozens of objects are artfully displayed, including marbles, a hammer, piano keys and a door knob. The piano keys are from Rusty’s childhood piano.

“Its provenance was never established, but it dates from the time of Louisa May Alcott,” says Rusty. Alcott, like Rusty was from Foxborough, Massachusetts. “It was a two string piano, with a creaky soundboard.” The legs of the table are from that same piano. “All the things here mean something to me.”

This cabinet of curiosities, I discover, is only the tip of the iceberg. “Would you like to see the Box Room?” Rusty asks.

Down the hall, the Box Room is dominated by more marvels — an entire wall, in fact, of what Rusty calls 3D collages, boxes made into art using personal mementos as the media.

He makes these collages out of cigar boxes, his mother’s old cheese boxes, tomato crates, roasting pans, and a crate that was used for baking deliveries in Portland, Maine. That latter one is filled with “bells, beads and balls.” “I like the alliteration,” says Rusty.

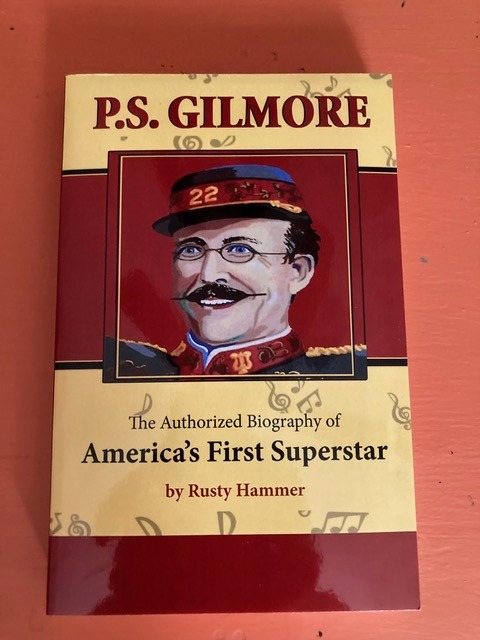

Another is dedicated to P.S. Gilmore, an old band leader who has been called America’s First Superstar. (In 2006 Rusty wrote an authorized biography of Gilmore.)

While I am gaping at Rusty’s dazzling concoctions, Rusty brings out several more boxes — tiny ones, including old sample cases, a Kiwi shoe polish can, vintage cigarette cases, Celestial Seasonings tea cans, a Dunhill pipe tobacco tin, even an old pocket watch. All are exquisitely filled with souvenirs from his life.

He started creating the boxes just before the lockdown and worked on them throughout the pandemic. “They are not for sale. I sold one of them and then decided that I wouldn’t sell anymore. I like them too much,” Rusty says quickly. “Doing this, I feel like an artist. I can’t explain it and that feels right.”

Lying in the corner of the Box Room is Rusty’s tuba. On the door is a paper bag – Lennie Kesl drew a hammer with the name Rusty on it. Was he always called Rusty? “My mom named me Hilary. But soon after an uncle started calling me Rusty.”

Marie points out one of her face sculptures on the wall. It was an anniversary present for Rusty – it is adorned with Xs and Os.

Both have their own spaces to do art here. In Marie’s studio she shows me a triptych she is working on. Looking at the swaths of blue paint, I can’t help but wonder – will a panther invade this one, too? “I don’t enjoy painting,” she admits. “I like it when it’s done.”

She feels freer doing the face sculptures. “Those are fun.” When she points out her mother’s sewing machine, I ask, “Do you sew?” Of course she does. She made the dress she is wearing from fabric she brought back from their trip to China – one of many stops in their global explorations. The blue sleeveless smock with white and red swirls looks like a Miró painting.

Rusty’s spacious garage workshop is one of the reasons the Hammers bought the house. There another dog, Mona Lassie, overlooks one of two large worktables.

Rusty says he’s non-plussed when something doesn’t work out. He tried to do the Artful Doggie, for example, and it didn’t work. Same with Sherlock Hound — “although Marie liked it.”

Rusty has hung a series of bells there. “Do you play them?” I ask.

Of course he does. “Sometimes I just have to wail away.”