By Tony Wong Palms

. . .

Through January 16

Tampa Museum of Art

Details here

. . .

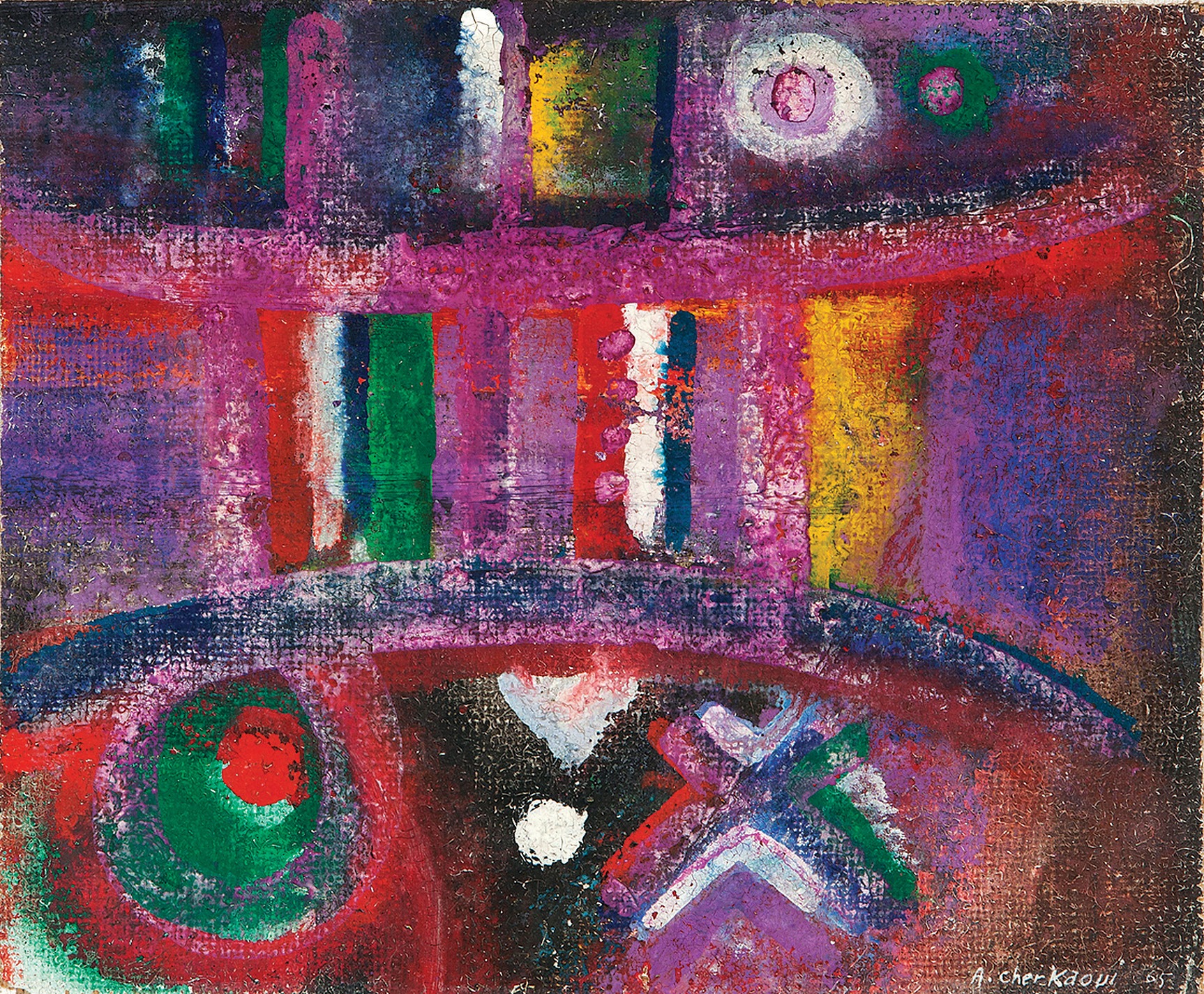

The exhibition, Taking Shape – Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s has been on view at the Tampa Museum of Art (TMA) since September 30, 2021. So much has happened in these few short months, thanks in part to a pandemic not ending, that battles personal and public both in front of the nose and far beyond the horizon are drawn out and magnified – making these museum oases ever more welcoming.

In this exhibition, TMA brings a bit of the wider world to broaden and brighten our socially distanced bubbles. Though some would argue that even during “normal” times we all live in some sort of bubble, the pandemic just exaggerates this isolation and narrowness.

. . .

. . .

While NASA is sending the James Webb Space Telescope to peer deeper into the cosmos than any other instruments have ever done, Taking Shape looks Earthward at a part of the planet frequently in the news – a place some of us may have even traveled to, and all of us depend on for supplies of oil and delicious hummus. And yet, even as we consume, deep-seated fear and mistrust stir regarding the people living in these lands.

It’s a good balance to have this outward and inward, micro and macro exploration in the making of the artworks in this show.

. . .

. . .

As the title states, this exhibition covers four decades of human time, 1950s to 1980s, during which unpredicted defining moments etched memories into the boomer generation and into history, all with interwoven connections and influences – the post-World War II Cold War, the Polio Vaccine, Castro leads the Cuban revolution, the Civil Rights Movement, Elvis, Bob Dylan, Muhammad Ali stripped of his world boxing title for refusing to enter the US army, the first human heart transplant in Cape Town, Andy Warhol, Anwar Sadat, Yasser Arafat, Golda Meir, Saddam Hussein, Neil Armstrong walks on the moon, Egypt and Israeli conflict, women’s rights, gay rights, bellbottom pants, the Ayatollah in Iran, Tiananmen Square… all while the world population grew from 2,584,034,261 in 1951 to 5,237,441,558 in 1989.

Besides the span of time, Taking Shape covers a vast geographic area from West Asia to the Middle East to North Africa. The number of countries in this realm – about 14 of which are involved in this exhibition, the many languages, religions, cultures, political regimes, and the diverse ethnic populations with all their ancestral branches – make this exhibition more of an overview, an introductory 101 course if you will, of this very rich and complex region anthropologists have called the cradle of civilization.

. . .

. . .

These 90 or so works from the collection of the Barjeel Art Foundation are grouped into several general themes – Decolonization, Hurufiyya, Sufism, Geometric Abstraction, The Body and Gestural Abstraction. The exhibition organizers have provided abundant informative labels, including artist bios and references.

The Decolonization, Hurufiyya, and Sufism groupings can be described as origin stories, stories relating to a people’s self rule, language and religion. Geometric Abstraction, The Body and Gestural Abstraction groupings focus more directly on style, visual language and aesthetics as learned from the West.

. . .

. . .

This almost encyclopedic range provide a banquet of source materials to explore and examine. One of the artists in the exhibition, Abdullah Benanteur, a pioneer of Algerian modernism, in 1962 referred to the postwar period as the second Arab renaissance.

. . .

. . .

As to the first Arab renaissance, Nadia Mavrakis, CEO of Culturinga, an organization that promotes and preserves the heritages of the North African, Middle Eastern and West Asian regions, writes in “The Hurufiyah Art Movement in Middle Eastern Art” that during the Arab renaissance in the late 19th century, “While al-Nadha [Awakening] represented a period of revival of traditional literature and poetry, it represented a complete Westernization, rather than traditional revival, in the visual arts. This process started when Ottoman sultans and Mohammed Ali of Egypt encouraged Western art as part of their modernization policies.”

. . .

. . .

With postwar decolonization, Western-educated artists, while mastering new vocabulary, methods, materials and values, began looking inward toward their own heritage to reclaim their identity – and developed the alchemic process of fusing these two impositions in their lives. While cloaked in Western garb, the art works carry very different meanings when compared to their European counterparts.

In this exhibition are some of the artists who perfected this synthesis.

Two paintings in the show by Jafar Islah who studied architecture at the University of California, Berkeley on scholarship from Kuwait University, cite Paul Klee as an influence. Islah adopted the concept “less is more,” not from the Western minimalist movement, but from the writings of Abu Nasr al-Farabi, the medieval Islamic philosopher.

. . .

The stately wood sculpture titled Interform, reminiscent of Barbara Hepworth but a bit more angular, uses elements of Islamic lines and curves. It is by the Lebanese Saloua Raouda Choucair who studied with Fernand Léger at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Her works draw on essential Islamic design elements, Arabic verse and music.

Hurufiyya and Sufism are the quintessential identifier of this region. Hurufiyya is using the Arabic script or lettering as the main visual element. Many examples of Arab script are sacred and sourced from religious rites, of which Sufism is considered the more mystical.

. . .

. . .

A prime example of this is Omar El-Nagdi’s large-scaled Untitled from 1970, composed of rhythmic graphic strokes of the numeral one, which shares in form the first letter in the name of God (Allah). Omar was in Giorgio de Chirico’s avant-garde circle before moving back to Egypt and joining the Liberal Artists’ group, part of Cairo’s art community.

. . .

. . .

Calligraphy, as in almost any written language, provides great potential for design and personal expression. The artist Madiha Umar from Syria started the Hurufiyya art movement. In 1949 she published an influential paper that might even be its manifesto, “Arabic Calligraphy: An Inspiring Element in Abstract Art.” Her Untitled 1978 water color shows how much her use of text has evolved the manipulation of calligraphic lines.

. . .

. . .

Egyptian Hamed Abdalla’s acrylic painting captures movement in a very immediate moment where calligraphy joins expressionism and could easily cross over to being part of Gestural Abstraction. As in almost every piece in the exhibition, there is no hard edged boundary between the various themes.

While some consider abstraction and non-representation as synonymous, and they are not, here abstraction in even in the most non-representational pieces portrays life and identities – not with every specific detail of photo realism, but more in the poetic haiku sense, where it takes a moment to sink in, to see into expressions of reality.

Taking Shape – Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s-1980s is drawn from the collection of the Barjeel Art Foundation based in Sharjah, UAE and includes work by artists from countries including Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Qatar, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE),