. . .

“There are some topics so important that we wanted to do it face to face so we can see and hear from you,” says African American Heritage Association President Gwendolyn Reese.

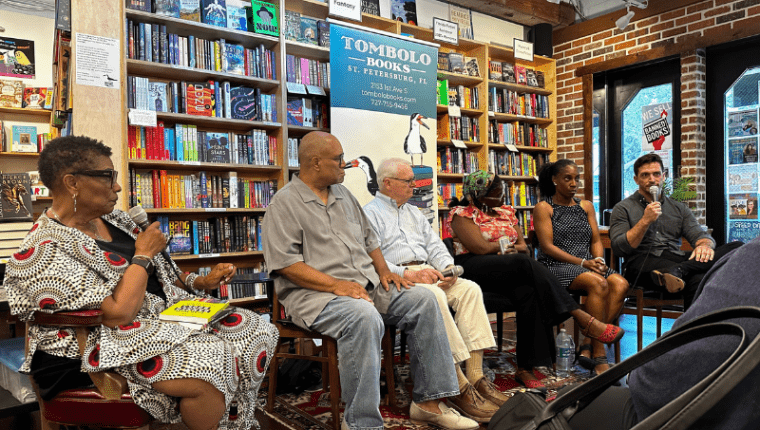

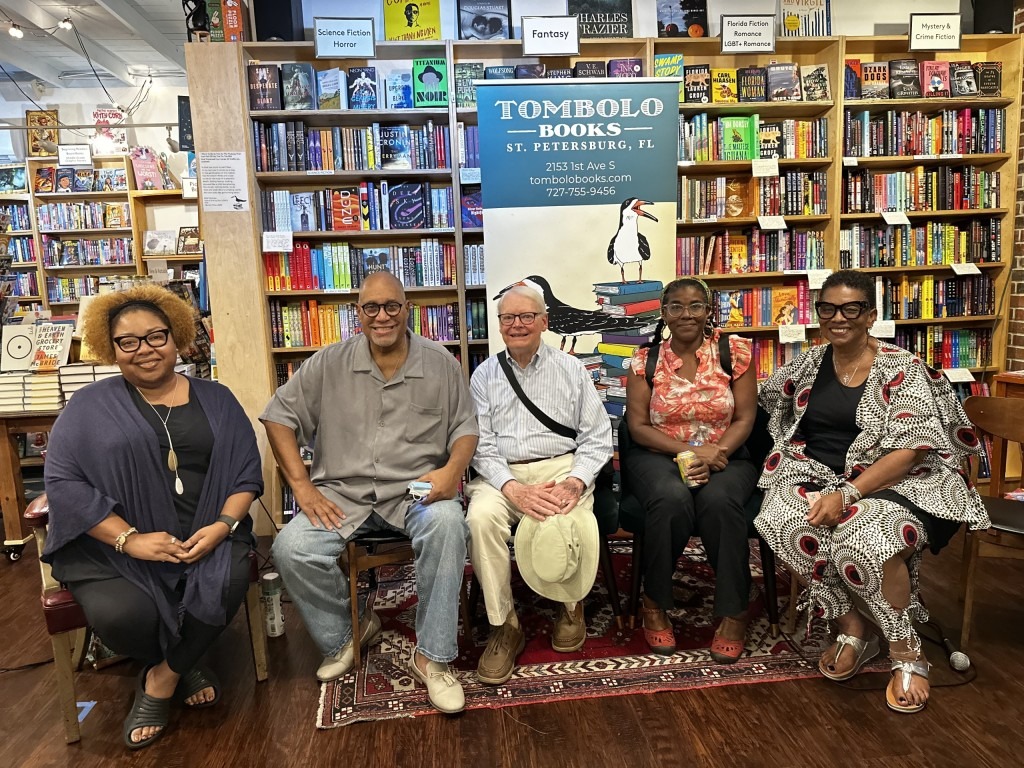

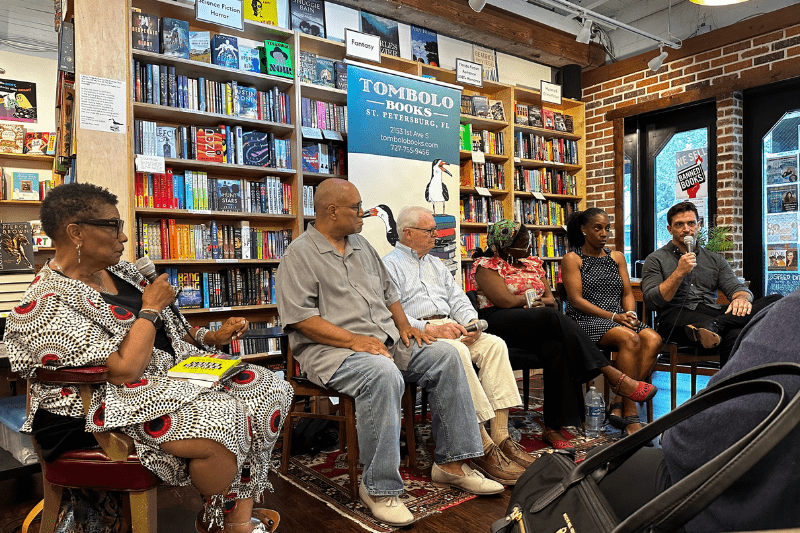

The African American Heritage Association (AAHA) held one of the few in-person Community Conversations since the series began more than three years ago. Community members joined Reese at St. Pete’s Tombolo Books on August 16 to discuss the recent book bans in Florida school districts.

Reese says it is “angering” that certain books are being placed on a sort of blacklist in educational settings around the state. Between July and December 2022, Florida state school districts have banned over 350 books, according to the nonprofit organization PEN America.

Titles on the long list now include children’s books like Nya’s Long Walk: A Step at a Time by Linda Sue Park, young adult novels such as The Nowhere Girls by Amy Reed and classics like Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye.

Gov. Ron DeSantis has denied that any books are being outright banned, though his administration has pushed through sweeping legislation that allows for books to be removed and reviewed if any parents of school children object to their content and availability.

“You can ban the books, but you can’t ban us from reading them,” Reese exclaims.

Panelists in the conversation included Carl Lavender, former Chief Equity Officer at the Foundation for a Healthy St. Pete, Dr. Charles Dew, retired professor and author of The Making of a Racist, Jake-Ann Jones, author and writer for The Weekly Challenger and this year’s Creative Pinellas Artist Laureate, Nikki Hill, educator at Gibbs High School and Will Baldwin, member of the AAHA.

“When we talk about banning books, we’re talking about one of the many inequities that’s happening around the country and the state of Florida,” Reese says.

Baldwin says he believes it’s hypocritical of a nation “so bent on protecting the First Amendment right” to ban books at all, and adds he wanted his daughter to have access to everything.

“I want to be able to parent in the household and not have the school do it for me,” he says.

. . .

You can read about the new

“I Love Banned Books”

book club for kids here

. . .

Baldwin, who grew up in a white suburb of St. Pete, admits he was never taught the African-American community’s contributions regarding the city’s founding and building. He likens books being pulled off shelves these days to the whitewashing and cherry-picking of historical facts — the same skewed history he received in his household growing up.

Hill, who taught English and has been an educator for 19 years, notes that some books being banned are classics that have been read for years in the classroom.

“[These books] allowed us opportunities to be able to grapple with historical topics that were uncomfortable,” she says.

Hill, a daughter of a librarian, draws a parallel with the Ray Bradbury novel Fahrenheit 451 — one that has been banned in certain Florida schools and describes a society that burns books that are deemed contentious — noting that she never thought we would see the day when we would call for the banning of books if we don’t like their content.

“Books are the tools that we use to be able to make sense of the world,” she says, adding that children will only be deprived of profound literature with ongoing book bans.

Jake-ann Jones, co-author of Sometimes Farmgirls Become Revolutionaries, calls the banning of books a kind of denial and erasure, while Dew sees it as “putting our lot in with the People’s Republic of China, where books are regularly banned.”

“I see book banning as an act of cowardice,” he says, noting that it has gone on throughout history in places like Hitler’s Germany, Stalin’s Soviet Union and Pinochet’s Chile. “People don’t have the bravery to confront the ideas that challenge theirs, and it seems to me that’s the antithesis of education. It’s not furthering knowledge – it’s trying to destroy knowledge.”

Lavender says it sparked anger in him when Toni Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye was the first book the district banned.

“This is a powerful journey where a character comes to life, and you are moved to such a place of inspiration, motivation and determination,” he explains. “And why would anyone want to keep that from you when so many young people lack those areas of motivation?”

This isn’t the first time there has been a movement to ban information in this country, Dew says, pointing out that beginning in the 1830s, the subject of slavery in debates was off-limits for 30 years. It ultimately led to the bloodiest conflict in our history, the Civil War.

“To close off debate, to close off consideration of ideas, is very dangerous,” he states. “We only have to look at our own history to see this.”

Lavender posits that politics are behind any recent statutes to pull books from shelves – and behind the way Black history is being taught these days, as the new Florida curriculum maintains that slavery could be viewed as beneficial to the enslaved because they learned trades and developed skills.

Dew agrees – “I think Florida is a case study for this because our governor wanted the Republican nomination for president and figured this was the most direct path to get there.”

“I also think it plays into the fear of some whites who feel dispossessed,” he goes on. “That if they’re not getting ahead, it’s because somebody else is responsible. There’s always that ‘other’ that has to be blamed.”

Baldwin feels it’s laziness and fear of not wanting to confront personal shortcomings and the issue of race in the country.

“It’s difficult to come face to face with the racism in your own family, maybe your own personal behaviors,” he states. “And it’s easier to just ignore it, to claim that you’re colorblind. And it’s easy to ban things rather than to be a parent and just monitor what comes through the door.”

Hill says there’s a lot of shame when confronting the country’s history, pointing out you’re either the people sitting at a lunch counter trying to integrate public spaces or you’re the person throwing things at the Little Rock Nine.

“There’s a bit of shame in thinking that perhaps historically you were on the wrong side of things, and that is not something that is comfortable to think about,” Hill asserts.

She also feels it’s about power. If white children learned the atrocities committed against Black people while learning the contributions and gains Black people attain while enduring systematic racism, white supremacy would weaken.

Reese added Lenice Emanuel of the Alabama Institute for Social Justice to the panel, who notes that shame is a factor in seeking to whitewash history or remove books from shelves. She says that the governor of Alabama has even asked educators in his state to remove a resource book for Developmentally Appropriate Practice, which informs them of techniques used to create welcoming environments for children of color and LGBTQIA+ young people.

“It’s just a level of almost evil that’s so emblematic of what has always been to me at the root of racism,” she says. “This desire to keep people ill-informed or not educated because they understand that there’s power in knowledge.”

Lavender notes that there are solidarity movements pushing back against the book bans. Dew says that more “white voices” would be crucial to any solidarity movement alongside African Americans in railing against bans and whitewashing of history.

“We have got to build a multi-racial democracy in this country – and the only way we’re going to do it is if white people step up and say, ‘We’re not going to take this stuff anymore,’” he says.

Hill agrees, stating education “will have to come from us” – and it must be a community effort of white and Black people to ensure that children learn the facts of history, however uncomfortable they may be.

Originally published in The Weekly Challenger