“Physical Listening” Workshop

. . .

. . .

What can dancers bring into the equine arena?

That was the first question that framed the conversation at Hillsborough Community College (HCC) this spring, when the Visual and Performing Arts (VAPA) Guest Artist Series and Dance department presented Interspecies Journey by The Equus Projects.

The performance was accompanied by two days of physical listening workshops which gave insight into how veteran choreographer, dance educator and Equus Projects’ artistic director, JoAnna Mendl Shaw, creates site-specific performances that bring horses and dancers into shared exchanges that prize “ego-less” dancing.

Shaw’s company, The Equus Projects, tours throughout the U.S. and Europe, creating site-specific works in immersive collaboration with local communities. She has taught on faculty at NYU, The Juilliard School, Alvin Ailey, Princeton, Mount Holyoke and Montclair State, and recently authored Physical Listening, A Dancer’s Interspecies Journey.

Before the first workshop early Friday morning, HCC Dance Director Christina Acosta pulled the curtains back from arched windows, transforming HCC’s second floor dance studio from a blackbox theater into a sunlit space. The outdoors begin their slow creep inside.

Shaw, flanked by her two dancers Kat Reese and Clement Menash, welcomed us into the fold.

Shaw details how the company is trained in natural horsemanship, and practice hyperawareness and tactile communication skills to connect with all sentient creatures — horses and humans alike.

Shaw says she was first asked to enter this realm at her alma mater, Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. The dance department organized a fundraising event that brought together the equestrian center’s bucking, rolling horses and Shaw’s choreographic talents.

“For me, I felt like I was [previously] thinking my way through choreography and when I started really investigating this work, it started coming from a very different place,” Shaw describes. “Crafting the shape of the content actually becomes super important because you’re working from such an internally felt place.”

The film, Imprinted: Dancing With Foals, provides the scaffolding for Equus Projects’ evening performance later that night — a blend of screendance and live dancing that Shaw says starts as a lecture-demonstration and slowly evolves into something more performative.

One clip from the film shows Shaw gently reaching towards the looming shape of a dark, black mare, who tentatively steps one hoof, then another, into a barn.

In the next moment, Shaw delivers a foal being born — a soft moment of release, a mess of limbs, the promise of breath inhaled afresh. Another scene entwines Reese and Menash in an affectionate pas de deux, exploring the sensations of grooming, brushing, and caring for these horses and their young.

What are the rules of engagement?

Back in the studio filled with a mix of community members, local dance professionals and HCC dance students, Shaw defines “physical listening” and notes how Equus Projects works this way to give the horse a voice.

Humans have moved with horses for thousands of years as riders, farmers and jockeys. But to have a successful dance partnership with a horse, you must be attuned to their needs and impulses in a different way. You walk side by side, in tandem, hand on their shoulder.

“If we walk in front of them, they’d be lost given their vision,” says Shaw. Walking side by side is a less dominant position, and the dancers practice soft focus to make the exchange more personal.

“What you do with your eyes makes a difference,” adds Shaw.

In a studio sans equine partners, we engage in the “walking score” with one another. Scores are rules of engagement, a set of directions that determine how the dancers will perform. In Shaw’s walking score, we prioritize the eyes by navigating around one another. She instructs us to shift our focus to the spaces between passersby’s feet, then to the pelvis.

In our periphery vision, she asks us to keep track of one partner. This quickly evolves into two partners. Without verbally alerting anyone who our partners are, we must triangulate between these two people in what becomes a complex game of tic-tac-toe.

Every time one person shifts, it ripples outwards, and the rest of the room morphs shape to accommodate.

This kind of intimacy and amount of concentration is exhausting to sustain. The score concludes. Shaw instructs everyone to take a break when she notices the back of the room beginning to fracture — shifting eyes and the slightest vibrations of distraction.

“With horses, attention matters,” shares Shaw. “You have to own that shift in attention because they will sense it.”

How do we practice generosity in our leadership?

Reese and Menash take over the next part of the workshop and begin the “sponging score.” Reese stands in front of Menash and begins a quiet swaying that suddenly shifts into a sharp poke of elbows and knees before settling into a rhythmic swing-pause-swing pattern.

Menash’s eyes never leave Reese’s form, but rather than copying her, he “sponges” her energy and begins dancing in a complementary fashion – inspired by her shifts of weight and changes in level.

We disperse, instructed to find a partner and give it a try. As a leader, I attempt to make my changes as legible as possible, communicating my mood in tempestuous outbursts and soft whispers.

When the time comes to switch leaders, I am vexed and invigorated by the puzzle. Be it horse or human, we often mimic to fit in, but this is asking for energetic alignment. How can I echo what I’m seeing without direct imitation?

What is the difference between hearing and listening?

“It was interesting because I grew up dancing and riding horses five days a week, but I never thought about how they informed each other,” says Reese, who often uses these practices in everyday life.

“It has informed my teaching a lot… the skills that I would use to get a horse’s attention, to deescalate or bring up energy – I use those same kinds of tools on students when they’re very noisy or feeling stuck and tired.

“It’s made me more aware of the choices I have that are more generous.”

Shaw notes that when dancing with horses, the equines are always negotiating for leadership, which is why sponging becomes vital. The dancers must tap into an animal’s consciousness without mirroring the animal.

“With horses we can’t imitate, or we’d be on all fours eating grass,” remarks Shaw.

In another scene from Imprint, the mare’s neck arcs gracefully – and Shaw curves her own body to point and extend in a similar direction. Improvising as if it were all pre-planned, the horses takes a step, and so does Shaw.

How can we live in “space/harmony” together?

Shaw instructs that any time you’re put in a leadership role, your role is to allow for the success of the people following. When you relinquish leadership to a partner, it’s important to understand why that has happened and for what purpose.

The final parts of the workshop involve a “tracking score” and learning how to “frame” one another. In the first iteration of the tracking exercise, we must keep the same distance between our pelvis and our partner’s pelvis. Then, we are given the freedom to track any of our body parts — an elbow, the sternum, an ear — to an area of our partner’s body.

The leader dances without knowing what we, the followers, are tracking. Twister-like negotiating ensues as the follower attempts to keep the same spatial distance from their leader. It’s a gauntlet for our nascent physical listening skills as we attempt harmony.

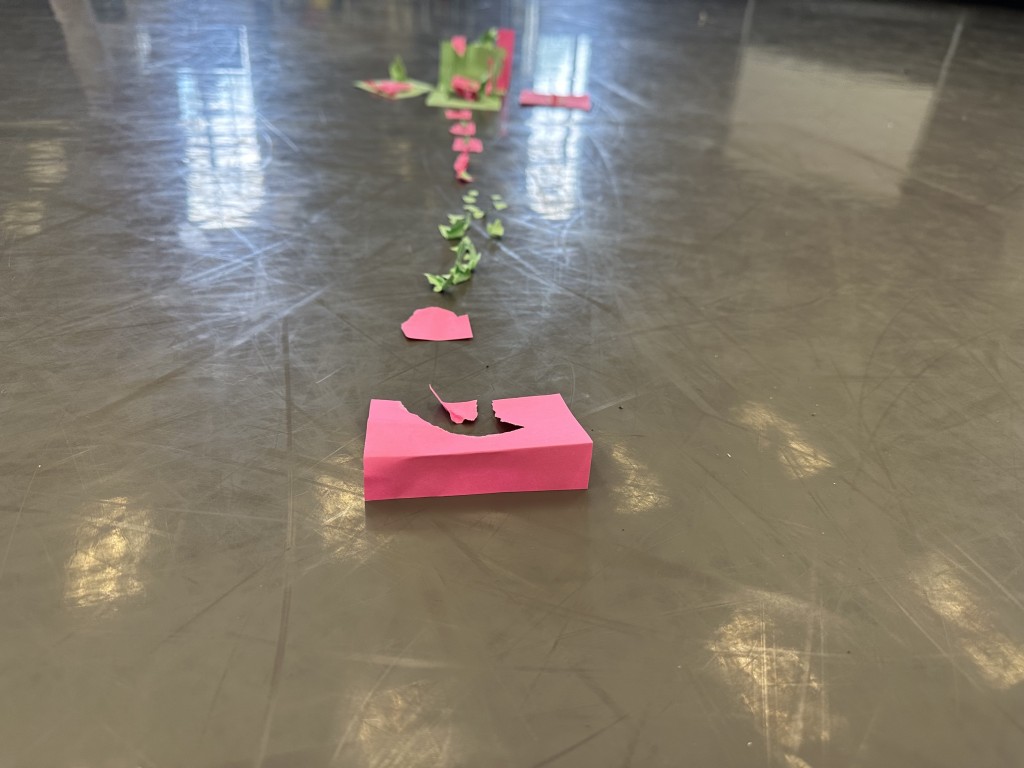

The final task involves creating a solo with an object and then framing that object with a partner. Shaw describes this rather complex idea as running commentary — not mimicking the object, but finding a way to present it to the audience so that it maintains its own integrity and autonomy. The applications of adapting from object to horse in this exercise are tangible.

The group watches one framing example unfold as Menash dances with an HCC student whose object is a baseball cap. Menash does a backwards roll, filling in the negative space around the hat. Shaw tags Menash out and herself in. With a ball in hand, she tosses it into the air using the timing of the cap’s twisting as an anchor.

“We have to frame what it is we want the audience to see about that creature,” says Shaw.

“It’s ongoing research into what communication really is,” reflects Menash.

“The ongoing research of physically listening is asking, how do I translate the empathy I have towards horses? Because we don’t speak the same language, so I really have to use my eyes, ears and spatial awareness to be able to communicate with them.

“How do I translate that to dancing with people or humans in space?”

The workshop concludes and I pack up my bag. Taking the stairs out to Ybor City’s main drag, I felt acutely aware of the shift in my awareness. Tracking, sponging, walking, questioning.

“This romantic notion of dancing with horses is really about wanting to learn something about myself,” narrates Shaw in Imprinted.