March 3, 2021 | By Robin O’Dell

Through May

Florida Museum of Photographic Arts

Details here

. . .

I have had conversations with people on multiple occasions about the future of photography. With digital cameras in everyone’s pockets, will fine art photography survive?

If so, what will it look like?

My opinion usually falls into two separate but connected responses. One, the camera has always been a tool that can be used in many different ways. Since the very beginning of photography, images have been manipulated and altered to reflect the artist’s intent. Yes, there are the elements of lighting, composition and content, but like a paintbrush in the hands of a skillful painter, photographic images can be put to all kinds of creative and potent uses.

The other, related response is that the easier it becomes to take a snapshot, the more the hands-on 19th-century processes are experiencing a comeback. People enjoy participating in the making of their art. Many schools are re-installing darkrooms and teaching alternative processes again.

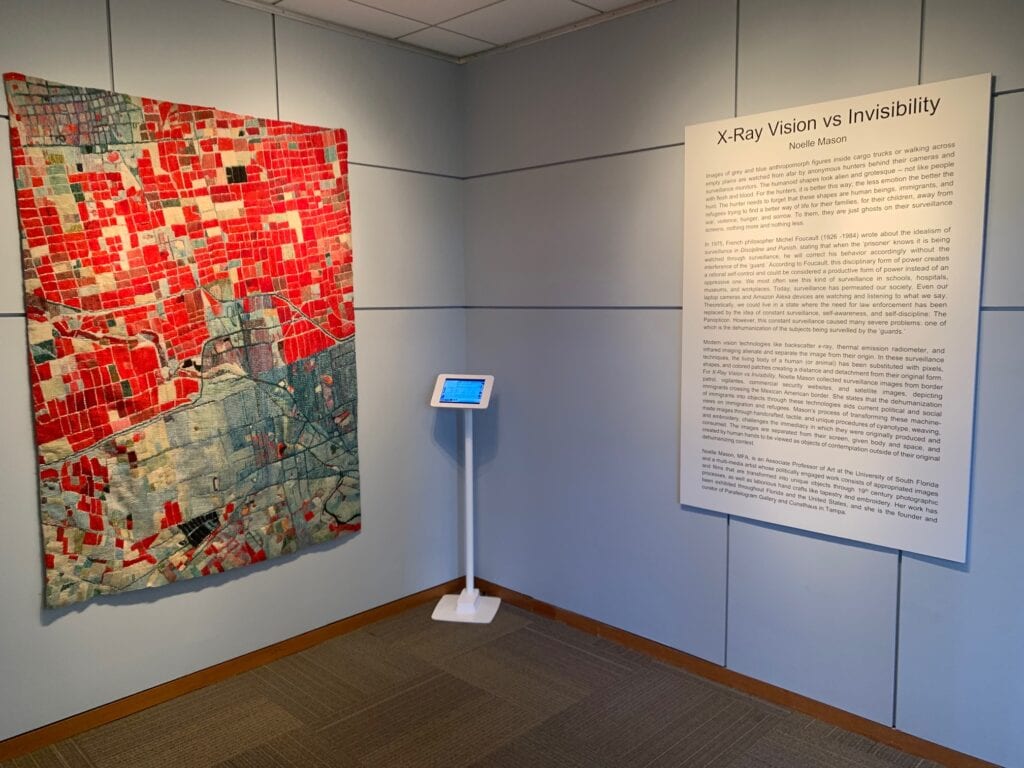

The exhibition Noelle Mason – X-Ray Vision vs Invisibility currently on view at the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts in Tampa, embraces both of these ideas in profound and moving ways.

Noelle Mason (American, b. 1977) has appropriated images of humans being smuggled across the Mexican border.

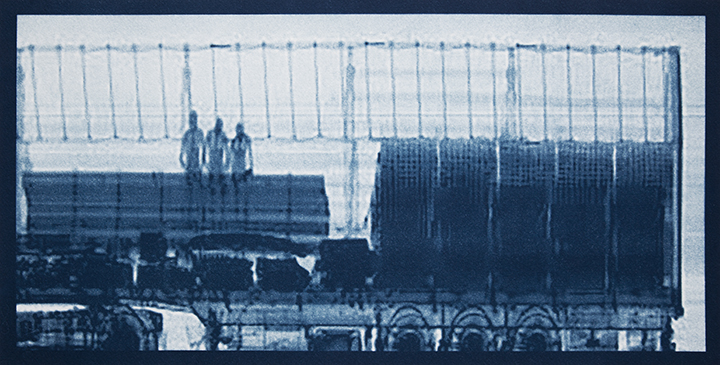

But these are not your ordinary images of beleaguered survivors or the empty water bottles and belongings they leave behind. Mason uses backscatter X-ray, thermal emission radiometer, and infrared images she has collected from security and border patrol websites. They trace the outlines of human bodies hidden in trucks and smuggled behind stacks of commodities in semi tractor trailers.

. . .

. . .

They are eerie and ghost-like. Ominous, in that you realize these images must have resulted in the arrests and incarceration of these desperate people.

It is what Mason does with these found images, though, that adds weight and solemnity to the exhibition. Mason takes these images and translates them in multiple hands-on processes.

Large cyanotypes are included that highlight the fugitives shown in a halo of white within a sea of blue. This is the same process that engineers used to make blue-prints until the end of the 20th century.

The technique dates back all the way to 1842, very soon after the original announcement of the first photographic processes in 1839. It involves using an iron salt solution for a very hands-on operation.

It is used to great effect in this exhibition. What were undoubtedly grainy black and white digital images originally, become rich cobalt blue poems to a struggle for survival.

. . .

. . .

FMoPA Curator Marieke Van Der Krabben explains in her exhibition text that it is the artist’s intent to transform machine-made images that depict the immigrants as objects. Mason strives to give them “body and space, to be viewed as objects of contemplation outside of their original dehumanizing context.” In this objective she succeeds.

Mason has an MFA in sculpture from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and a BA in studio art from University of California Irvine. These 3-D practices show up here in a series of intimate hand-created x-stitched maps. Images are translated onto cotton fabric where the artist has added a single cross stitch of thread for each digital pixel.

She has titled this series Coyotaje, referring to the Mexican/Spanish term used to refer to a person who smuggles people across the Mexican-American border. Indeed, in addition to the X-ray images of vehicles, this series also includes photographs of people attempting to cross the border by foot.

You can sense the enormous amount of time it must have taken to create these canvases by hand, adding weight to the solemnity of the subject. A film of actual coyotes being hunted, compared to border patrols and vigilante groups pursuing migrant people as though they are animals, adds a further serious and tragic note to the exhibition.

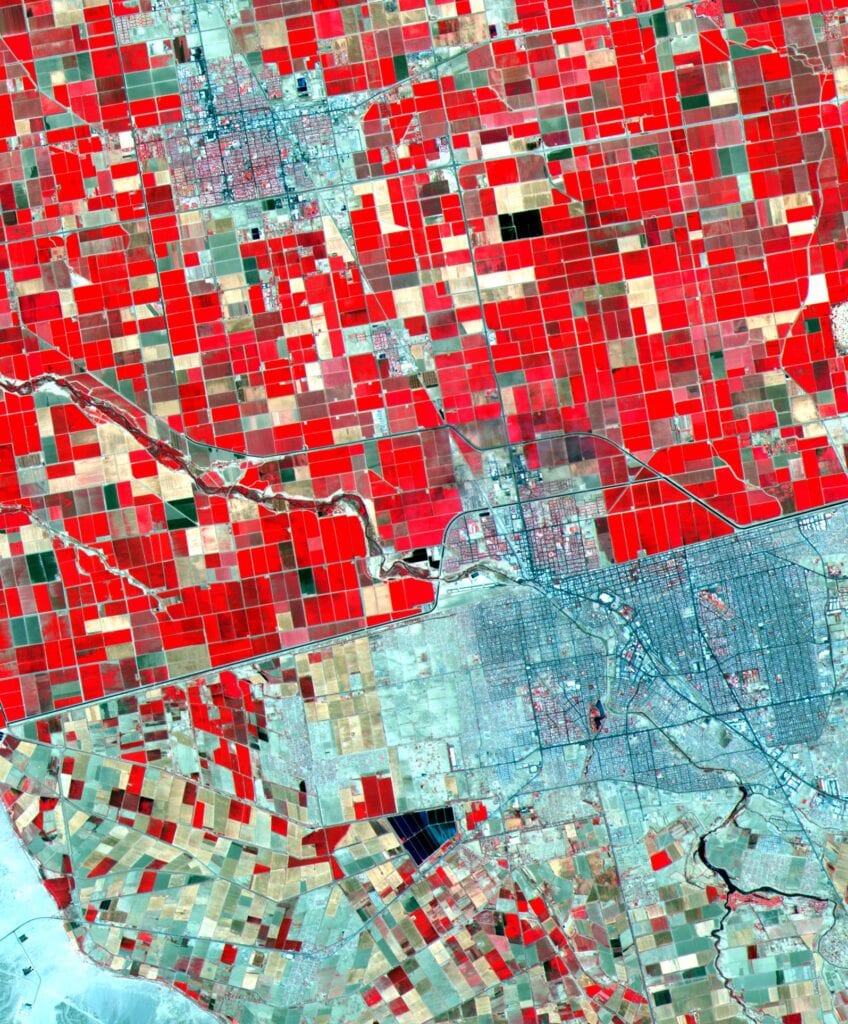

In addition to the small hand-stitched works are two large scale tapestries of hand-woven wool. They reproduce aerial images of the U.S./Mexican border taken by the Terra Satellite’s Advanced Spacebourne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer.

. . .

The tapestries were created in Guadalajara, Mexico by the Taller Mexicano de Gobelinos in exchange for the amount of money it takes to finance a family of four to migrate illegally to the U.S. They highlight areas of high conflict but are colorful, gorgeous and alluring – like fanciful images taken out the window of an airplane. They are translations of actual photographs, and the many colors reflect the stark contrast between the American side and the Mexican one.

. . .

. . .

The final objects found in the exhibition are rich collodion prints. These are date stamped and blurry, fascinating in their want of information.

The collodion process, also called wet plate process, requires a glass plate to be coated with an emulsion, sensitized, exposed and developed all while the emulsion is still wet.

. . .

. . .

In the late 19th century when this was commonly used, photographers were required by necessity to travel with portable darkrooms so that they could process the image immediately. A tintype is a kind of collodion print, although they use a thin piece of metal instead of glass.

As used in this exhibition, the objects once again invite close inspection and contemplation. The smallness in size, the fragility of the unframed glass plates, and the rich dark image require an effort to view.

The use of found images and handmade processes in X-Ray Vision vs Invisibility takes a subject fraught with controversy and divisiveness and creates a space to consider the humanity of people putting themselves in dangerous situations and risking their lives in hope of a better life.

Noelle Mason has performed this with skill and grace.

. . .

. . . Explore Noelle Mason’s work at noellemason.com

. . .

Robin O’Dell is the Curator of Collections

at the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts

. . .