January 24, 2020 | By Eric Snider

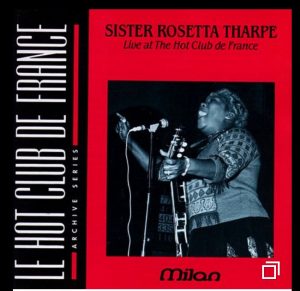

Sister Rosetta Tharpe — major star in the 1930s and ‘40s who narrowed the gap between gospel and pop music, and presaged rock ‘n’ roll — is hot again

Marie and Rosetta by George Brant

is onstage through February 16

at freeFall Theatre

Details here

The celebration of Sister Rosetta Tharpe — a pioneering artist who bridged sacred and secular music and has been recognized as the Godmother of Rock ’n’ Roll — is in full swing. After her death from a stroke at age 58 in 1973, her reputation and influence plummeted into an abyss. She was, after all, a black woman whose career had fallen off. She had lost a leg to diabetes. She was buried in an unmarked grave in Philadelphia.

After a slow but steady increase in recognition during this century, Sister Rosetta is enjoying her big posthumous moment. She was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018. She’ll be honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award at Sunday’s Grammy Awards.

Bay area residents have the opportunity to share in the Sister Rosetta revival by attending a performance of the play Marie and Rosetta at freeFall Theater,. The two-person piece, by playwright George Brant, was first staged in 2016.

Marie and Rosetta tells the story of Tharpe’s relationship with Marie Knight (played by Hillary Scales-Lewis), a fledgling gospel talent who Tharpe (Illeana Kirvin) recruited as a protege in the late 1940s, beating out her rival, Mahalia Jackson.

Set in a Mississippi funeral home where Tharpe is staying during a tour stop, the pair — rehearsing for that night’s show — banter about racism, oppressed womanhood, bad husbands (or “squirrels,” as Tharpe calls them), motherhood (Marie, 23, has two children, Tharpe had none) and more. Along the way, the play adroitly tells Tharpe’s personal and artistic story, her triumphs and struggles.

But it’s the actors’ musical performances, both alone and in tandem, that give the play its many sublime moments. The characters, feeling each other out, begin hesitantly, with snippets of traditional gospel songs. The prim and serious Marie disapproves of Sister Rosetta’s hip-shaking passion. Sister, for her part, is determined to get her charge to loosen up and have some fun.

Soon enough, they clash over Sister Rosetta’s unbridled ferocity in “Rock Me,” a late ’30s hit that melded gospel themes with Tharpe’s blues-style belting and the swinging horns of Lucky Millinder’s big band. They progress to “This Train,” a sacred song set to a boogie beat, and then to strictly secular material like “I Want a Tall Skinny Papa.”

The musical performances — with Marie playing an upright piano and Tharpe on her trademark guitar (pre-recorded) — culminate in “Strange Things Happen Every Day,” the first gospel song to cross over to a secular audience.

“Strange Things,” a major hit in 1945, is in every aspect a proto-rock ’n’ roll number — right down to its guitar/piano/bass/drums instrumentation. The tune features Tharpe’s spirited guitar work, including a solo. When she later switched to an electric Gibson SG amped up with distortion, and played it with hip-shaking swagger, she influenced the likes of Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Jeff Beck and Jimi Hendrix.

Kirvin and Scales-Lewis do an admirable job of evoking the musicianship of their characters — Tharpe, a raucous belter and Knight, a more cautious, measured singer. (This contrast can be heard in the various records they recorded together.)

Further, the stage performances have an impromptu flavor that evokes two women getting to know each other, striving to find shared musical ground — and succeeding. (Kirvin replaced the original Sister Rosetta four days before the play opened, which may have helped add to this extemporaneous quality.)

The song sequence in Marie and Rosetta serves as a history lesson about the origins of rock ’n’ roll — especially as it relates to the struggle between the secular and the sacred. The tunes vividly show the commonality between gospel and blues, while highlighting the tension between the church and singers who dared to venture into more worldly themes.

Sister Rosetta claims that the unbridled joy she projects in her music is in itself a celebration of God, who would approve. “God don’t want the devil to have all the good music,” she declares.

Tharpe was all but ostracized by conservative churchgoers for playing nightclubs and releasing secular material. While she was conflicted about certain aspects, like performing alongside scantily-clad women, she never relented — and continued to meld the two traditions, even engaging in guitar battles at the Apollo Theater in Harlem.

It’s nothing short of remarkable that, in the pre-Civil Rights Era, a guitar-slinging black woman, the daughter of cotton pickers in Arkansas, could rise to international fame, help ease the divide between gospel and secular sounds and play a significant role in shaping the popular music to come. She accomplished all this by the sheer dint of her determination and unwillingness to be cowed — along with the talent to pull it off.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s importance was lost, but now it is found.

See Sister Rosetta Tharpe herself

with an impassioned performance of “That’s All”

Sister Rosetta’s electrifying version of “Down By The Riverside”

Find out more about Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s music here

The PBS documentary by Mick Csáky, Sister Rosetta Tharpe: The Godmother of Rock & Roll