Courting Creativity with

Carrie Boucher’s

Justice Studio

Boucher’s visiting art program at the Pinellas County Juvenile Detention Center doesn’t just give teens a fun break — it gives them inspiration and a feeling of accomplishment.

BY JULIE GARISTO | PHOTOS BY TODD BATES | Feb. 1, 2019

Artist and arts educator Carrie Boucher is in her element far away from institutions of privilege and prestige.

The young people she encounters — many of whom wouldn’t visit a museum or dream of attending art school — drive her mobile art mission.

Still truckin’ into newer territories, the NOMAD Art Bus founder has steered her posse to a new frontier in August. She founded the Justice Studio, an art enrichment program, at the Pinellas County Juvenile Detention Center. It’s the first project of its kind in our region.

Providing a mini manifesto, Boucher explains on her Patreon page what inspired her to begin merging art with youth outreach:

I had no premonition that I’d be walking (driving?) this path back when I was working my way through art school, but when funding cuts started pulling art programming from schools in my area I responded by building an art room inside a bus and taking to the streets so that everyone could have art class again. We go to places like group children’s homes, juvenile detention centers, domestic abuse shelters, and rec centers in areas of high poverty to make connections and facilitate joyful art experiences.

The Justice Studio idea had its first inklings when the Seminole resident drove her artmobile to JDC in May 2018 to be a part of “Good Moves: A Caravan of Sharing.”

She and her crew provided art supplies and lessons to the facility’s underserved youth who live throughout the Tampa Bay region. Other mobile nonprofit organizations, such as Bluebird Book Bus, Bess the Book Bus, Boards for Bros, Road to Artdom and Giving Tree Music, also participated.

As a result, recognition of Boucher’s efforts and uplifting mojo has spread across both sides of the bay. She received a $50,000 grant from the Tampa Bay Lightning, and from that grant, she has set aside $35,000 for her mobile art studio. The remainder of the grant has been split with Boards for Bros and Diversity Arts.

Currently, Boucher says she continues to need assistance to purchase materials such as paints, books and other items. Donations are still being accepted at her Patreon page.

Immediate progress

The project’s schedule started as a twice-a-month visit but has since changed to twice-weekly.

“We decided prior to launch that Justice Studio would be a weekly program because average length stay there is 21 days, so visiting two times month we might see the same participant only twice, which is not enough time to really start building relationships with them,” she explains.

“When we went into the first session (Sept. 6) and learned that youth also have no access to any art supplies when we’re not there, even during free time (because many youth have a tendency of marking/tagging their environment when given mark-making materials).”

During that session, a participant asked Boucher and her partners if they would visit three times a week. To assure that the group knew they were open and responsive to their requests, they found an intermediate, middle ground.

“The program was to be built by them, so we compromised to twice a week,” Boucher explained.

Visiting the Justice Studio

On the day of Creative Pinellas’ visit, Boucher arrives in jeans and her signature bandana and cat-eye glasses. Joining her, the equally casual and unfussy Kinsey Rodriguez, an art therapist, artist and group home instructor, and Kristin Eschenroeder, an artist and arts educator.

The three women look all like they’re headed to an Orpheum concert in their not-afraid-to-get-dirty street clothes.

Boucher has a limit on how many people can accompany her crew at JDC, and we’re told to leave our phones and other devices in the car. I don’t speak to the teens. I just sit back and observe their enthusiastic participation and help out with a little line painting.

On entering the facility some of the people in Boucher’s entourage lock their items in a locker in a no-frills, unadorned, circa-1970s admission office.

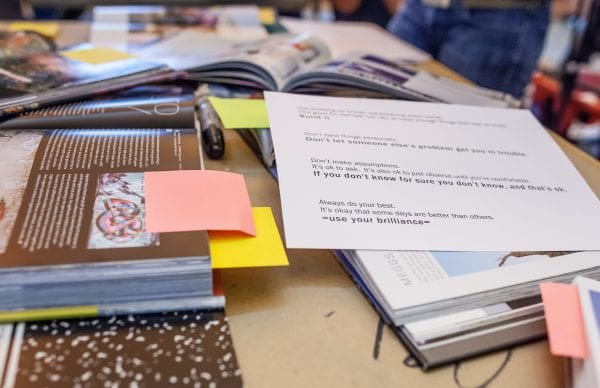

She signs us in, we walk through a metal detector and head to a rec room full of Post-It-bookmarked magazines and books that make both the teenager and adult in me swoon.

A Welcome Break

The instructors and three teens sit casually at a table not unlike what you’d see in a high school lunch room. One book, How to Draw the Darkest, Baddest Graphic Novels grabs the attention of the youngest male inmate, who’s around 14 years old. Another, a female, wears a sweatshirt and is visibly cold on the unusually chilly late-fall-Florida afternoon, tucking her hands into her sleeves.

The officer in charge, Sgt. Williams, dispatches the girl’s younger peer to grab a jacket for the shivering 16-year-old from another part of the building.

The older male teen in the group is visibly troubled, sighing and bending his head down. On the verge of turning 18, he confides that he’s being tried as an adult for theft and has to go to County Jail to serve out the rest of his sentence. Boucher leans in and speaks to him with a nurturing tone. She encourages him to keep up his spirits and do his best to keep practicing art.

“I’m determined to keep up my progress,” he assures her with calm sincerity.

Sgt. Williams says she only enlists trustworthy, well-behaved youth to participate in the Justice Studio. Artistic talent isn’t required; just a willingness to be creative.

Tough but approachable, Sgt. Williams looks you up and down and carefully metes out her words when she speaks to you. She doesn’t divulge much but shares that she’s done some creative work herself in her spare time — she creates lifelike infant baby dolls and has sold them on eBay (but isn’t actively doing so during our visit).

Taking Ownership of Their Work

We relocate to an atrium. Photographer Todd Bates and I observe the teens completing a colorful, geometric mural on its southern wall. The boys mix paints and the girl refines the lines and perfects some of the shading. I help with the outlines, tracing the penciled parts with a thin brush dipped in black.

Next to the mural, motivational posters aim to inspire with clever slogans. One reads, “Life isn’t about waiting for the storm to pass. It’s about dancing in the rain.”

A more relatable inspiration, Boucher shares that she trained the teens to plot out the mural design using a grid, and they pretty much faithfully re-created her design. The JDC inmates took some license with the shading and outlines, an act of experimentation the coach not only tolerates but encourages.

Reflections on the Justice Studio

Bates, who has collaborated with Boucher often over the past couple of years, says he was honored to be asked to help document Justice Studio.

“At the facility, I try to be a fly on the wall and capture as much of the experience as possible,” he said. “I know these kids have screwed up and are there for a reason, but also believe they need creative activities in their lives. I am so grateful there are organizations such as Nomad that can bring some joy to their lives.”

Ever enterprising, Boucher, has been working with Mitzi Gordon and Bridget Elmer on the traveling grant-winning SPACECraft Project. If her initial success with Justice Studio is a viable indicator, she and the team shout hit the ground running once again.

“What has surprised me most is how youth start to communicate on a much deeper level when in a small, supportive group environment and disconnected from the distraction of their mobile devices,” Boucher observed.

“They are not afraid to be vulnerable. In Justice Studio we’ve had deep, participant-led conversations about things like metaphysics, the relativity of time, relationships, government, and life’s struggles.”