February 11, 2020 | By Brooks Peters

Thoughts on James Baldwin’s novel, Giovanni’s Room

. . .

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin is one of those rare novels that literally changes lives. Numerous authors over the years have singled it out as a favorite, one that inspired them in fact to become writers.

Recently, BBC News listed it as “one of the 100 novels that shaped our world.” The Advocate placed it first on a list of the 25 best LGBT novels of all time. And yet when Baldwin wrote Giovanni’s Room back in the mid-‘50s it was a failure. His publisher, Alfred Knopf, who had launched him as one of the most prominent new writers of his generation just a few years before with Go Tell It On the Mountain, rejected it, calling it “repugnant.” One of his editors actually suggested Baldwin burn the manuscript or risk ruining his career.

The “problem” with Giovanni’s Room, a tale of a tortured love affair between two men in Paris, was that it dealt candidly with homosexuality, a subject that was taboo in mainstream culture and was still illegal in the United States.

But even more so, James Baldwin was African American, and there were no black characters in the novel. Some of his supporters felt he had abandoned the cause. Others felt he had sold-out, or was over-reaching. One friend called it “a book in drag.” Baldwin argued that he had been treated poorly because the powers-that-be thought he was being “uppity,” attempting a novel that clearly was the turf of better known figures, i.e., the establishment, such as Henry James and Ernest Hemingway.

Yet Baldwin was undaunted. He sent it to another publisher, Michael Joseph in England, who didn’t have the squeamishness of his American counterparts. The book was then published in the States by Dial Press in 1956, and in subsequent paperback versions that sold very well.

Over time, the novel has taken on its own iconic status, becoming one of Baldwin’s most admired books. In a telling twist of fate, it was recently reissued by Everyman’s Library, a division of Knopf.

Recently I picked up Giovanni’s Room again. I was looking for inspiration for my own novel, parts of which take place in Paris. I was struck by how wonderfully lyrical and completely modern his book is, even now. The imagery is startling — the psychological intrigues intense. The language may seem tame by today’s standards, the sex perhaps too couched, some of the dialogue stilted, the female characters at times borderline caricatures. But the themes Baldwin explored — the dangers of lying to oneself, of self-hatred and of homophobia — are as relevant today as they were back in the repressed 1950s.

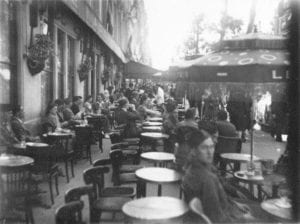

Baldwin knew the devastating impact these deceptions can have first hand. At 24 he moved to Paris, an exile by default who went abroad in order to write, but also to explore his sexuality with less restrictions and opprobrium. He mingled with other literary expats at Les Deux Magots and Cafe de Flore, notably Richard Wright, Terry Southern, Herbert Gold, Chester Himes and Alfred Kazin. He hobnobbed with Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and Jean Genet, as well as a tetchy Truman Capote when he traipsed into town for a visit.

But Baldwin, for all the glamour of his surroundings, was hardly enjoying the high life of expats as glorified by Hemingway. This was not Midnight in Paris. He was living hand to mouth, barely able to afford food, often crashing with friends, or finding cheap digs in the Latin Quarter, sporting rags and hand-me-downs, becoming as he put it, one of “les miserables,” a “lamentable.” At one point he even had to sell his clothes and his typewriter just to survive. At another, he was thrown in jail, allegedly for stealing bedsheets.

The seedy confines of Giovanni’s room, from which the novel takes its name, resembles a jail cell, a prison of the mind in which the couple live out their doomed affair. It was a hard, often unhealthy lifestyle, but one that offered Baldwin something he rarely felt back in the States — freedom. Not just as a black man, but as a gay man. While in Paris, Baldwin fell in love with a young Swiss artist, Lucien, whom he met at a bar not unlike the one depicted in the novel. Giovanni’s Room is dedicated to him.

The first time I read Giovanni’s Room, I too had escaped to Paris, as a high school exchange student living with a French family. A friend had given me a paperback copy of the book, suggesting it might “open my mind.” The cover drew me in, a pulpy sketch showing a handsome dark-haired young man posing seductively, his sensual eyes challenging the reader to take him on.

There was nothing immediately evident to indicate to me that Baldwin was black, and none of the characters in the book were either. At first glance it seemed to be the type of novel Gore Vidal might have written. Vidal’s The City and the Pillar, which had been published in 1948, had explored similar themes. But Baldwin’s writing, I discovered, had heart and soul, something noticeably lacking in Vidal’s. And Baldwin was determined to avoid clichés, to write a gay-themed book that did not end, as Vidal’s original version had, and as so many other homosexual novels had before it, in suicide.

Giovanni’s Room did open my mind, but it acted too as a mirror. I recognized myself in its pages. Even though I was still sexually naive, and inexperienced, I had witnessed many of the characters Baldwin chronicles in his book — the pretty boys, drag queens and hustlers who make up the demimonde of late night Paris. I loved reading about their drunken catfights, louche liaisons, the rough-and-tumble sex. I even knew someone like the character Jacques, a generous old queen who is a mentor to the protagonist David. I’d met an older man, also named Jacques, who owned a chateau in France. He took me to a gay bar with a rowdy drag show that was straight out of La Cage Aux Folles. Our friendship was all very chaste, aboveboard. Nothing untoward, as they say, happened. He was a gentleman. But I remember the thrill when he gave me 100 francs, no small sum to an 18-year-old then, and told me to treat myself to a night on the town.

I’d already been exploring Paris’s demimonde on my own. One evening, even though I had to be at school early the next morning, I snuck out at midnight and went to Le Drugstore, a brightly-lit American-style cafe on the Champs Élysées notorious for attracting prostitutes and their clients of both sexes. I had stumbled across it by accident one evening with school friends and promised myself I would go back on my own. That night I found myself sitting next to a handful of young men, rail thin and too cocky for their own good, reminding me of the “knife-blade, tight trousered boys” described in Giovanni’s Room. Some had bleached blond or hennaed hair, and wore leather jackets and boots. They chain-smoked Gitanes and drank Pernod. One of them whispered hoarsely in guttural French to his mates. I could barely make out what he was saying, but the gist of it was clear. He had just come back from “rolling” a john, a trick. The group of boys laughed raucously and joked about finding another.

I felt a powerful sexual tension while observing them, especially since one of the hustlers kept staring at me, but also because I felt I was reliving what James Baldwin had so hauntingly evoked. Despite my youth, I was desperate to be part of their world, and his world. Perhaps it was loneliness or a desire for what the French call “la nostalgie de la boue.” In school we had read Verlaine and Rimbaud, and were taught that to create great poetry and to understand life one had to push one’s senses to the absolute limit. In my own small way, I was charting that path, hoping to become a writer. I thought of the quote by Walt Whitman which appears at the very start of Baldwin’s novel: “I am the man, I suffered, I was there.” It cut very close to home.

Perhaps that is why Baldwin chose to write Giovanni’s Room in the first person. Baldwin said he was initially reluctant to do so, citing Henry James, whom he considered “the master,” as a critic of the practice. But ultimately I think Baldwin knew that readers would respond more viscerally to the story if it were told directly, not from a remove, to see the novel, as Stendhal wrote, as a mirror, reflecting reality, both high and low.

One can’t help but recognize shades of Baldwin in his chosen narrator, David, the handsome jock who shacks up with Giovanni in his fatefully dingy room. (David, it should be noted, was also his stepfather’s name.) In fact, the novel opens as David sees his own reflection in a window, a twist on the Narcissus legend, but also revealing of his character, since he only sees himself, rather than the world that lies beyond. Baldwin was writing his own memoir in disguise, almost as if he were channeling himself in David, for in fact it was in many ways his own story, his own experience, his own tragedy.

At first glance, David seems to be the polar opposite of Baldwin. He’s white, blond, well-built. He stems from a long line of Caucasian ancestors, a point he underscores almost guiltily. Born in San Francisco, David was raised in Seattle, then moved to New York and eventually Connecticut. By his late 20s, bored and feeling frustrated, he leaves his family for Paris to “find himself.” He’s also hyper masculine, almost a parody of the macho man of his day. He played football in high school, is called “Butch” by his dad, and exudes an All-American stoic reserve that seems light years away from Baldwin’s own raw emotional nakedness.

But David, like Baldwin, is rootless, a changeling. Baldwin was a bastard child, and David seems to bear a similar chip on his shoulder. He lost his mother when he was five. His father, who remarried, is aloof and unfeeling. He’s a loner, with few friends. Baldwin likewise never knew his father. His mother, a domestic, married another man who became Baldwin’s stepfather. They were not close. Like Baldwin, David is a heavy drinker prone to destructive binges. He admits that in one of them he exposed his true nature by making a pass at a sailor in a gay bar, shocking his friends, who believed he was straight. He’s also full of self-contempt, a deep-seated anger at the world that he hides beneath his steely armor.

Such existential despair was a common theme in film noir and tough Black Mask magazine mystery stories. Baldwin seems to be toying with the genre, structuring his novel around a scandalous murder case in which David is intimately involved.

David, for all his reserve, is a man of secrets. He hides a painful truth, one he’s succeeded in burying, claiming to others that he’d never slept with a man before. But then, he reveals to the reader, right at the outset of the book, an encounter he had with a young friend, Joey, near Coney Island in Brooklyn, when they were both boys. In a beautiful passage, Baldwin describes a brief encounter in which the two friends fall into each other’s arms and have exhilarating sex. Joey is described as “dark” or “brown” with “dark eyes” and “curly hair” — he is the other, and one can’t help but feel that on some level he is also a stand-in for a young James Baldwin.

The happiness that the two boys share that night is quickly extinguished the next morning when David shuts it down. Joey’s body “suddenly seemed the black opening of a cavern in which I would be tortured till madness came, in which I would lose my manhood.” Even the bed in which they’d lain “testified to vileness.” He cuts Joey off. And when he next sees him, David “picked up with a rougher, older crowd, and was very nasty to Joey. And the sadder this made him, the nastier… [he] became.”

It is this painful memory that sets the tone for the revelations to come, and one assumes the narrator will move beyond it, learn from it. That’s what novels are supposed to do. They’re journeys, lessons in life. But instead what we discover as we get further into Baldwin’s novel is that David is fated to relive this soul-killing over and over again. It’s the myth of Sisyphus — he is the homme fatal, fated to repeat this experience. But as with any type of sexual repression, or addiction, the result is much worse the next time around, a chain reaction of bad karma. And the next victim in his sights, Giovanni, will not, can not survive.

Shades of homophobia and self-hatred are deeply ingrained in David’s persona, and that’s the essence of the novel — that denying one’s true self will lead to destruction not only to one’s soul, but those around one. It’s easy to read David’s attraction to Giovanni, whom he meets in a bar where the boy works, as a romance. But Baldwin has something much trickier up his sleeve. This novel is actually an anti-romance, a Liebestod, or death song, told as a noir.

David describes his initial encounter with Giovanni as a seduction. Giovanni woos David, forces him to open up, to relax. He sees behind David’s mask. He takes him to bed that first night and David moves in with him. It all seems preordained. But that’s just how David is remembering it. How he has convinced himself it happened. And how he is relating it.

In fact when David first sees Giovanni he describes him as a magnificent creature of the jungle, a lion. He’s irresistible and all-powerful. It’s easy to overlook, however, the line in which David compares Giovanni to a figure on “an auction block,” in short, a slave. Slowly one realizes that it is David who is the lion and that Giovanni’s room will become the arena, and Giovanni the martyr.

Baldwin offers other hints to David’s dark side. It’s easy to see him as the affable jock, the All-American, a saint. But earlier in a scene at the bar, when an older gay man walks by, David feels disgust and derides this figure as “a zombie,” one of the undead. It’s a strikingly creepy moment. Time seems to stand still.

The haunting image is eerily reminiscent of the overly made-up pestilent fop who appears as a harbinger of the plague in Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, a book Baldwin admired. One also senses the influence of Poe’s The Tell Tale Heart, which is a story told in the first person, of a man who lives with a man, and then murders him. You hear Poe in the cadences of the narrator’s anguished, guilty revelations, in the oppressive Grand Guignol atmosphere, and the sense of impending doom, the death knell countdown to the inevitable fall of the guillotine and Giovanni’s death.

In a telling scene, David meets up with his flamboyant mentor Jacques, his reliable sugar daddy who always pays for his meals and drinks. It’s never really clear what their relationship is. Or was. Jacques is mystified by the way David treats Giovanni. He accuses him of being a sadist. And a hypocrite.

David in turn is repulsed by him and dismisses the old queens who prey on young men, asking: “Is there really no other way for you but this? To kneel down forever before an army of boys for just five dirty minutes in the dark?” But Jacques parries deftly: “Think of the men who have kneeled before you while you thought of something else and pretended that nothing was happening down there in the dark between your legs.” The comment feels like a Freudian slip, exposing something David has buried in his subsconscious. It unnerves him. Clearly David is not the innocent he claims to be and we as the reader have to wonder, how much else of his tale is a cover-up, a lie?

From there the narrative begins deliberately to unravel, fragment. Giovanni loses his job at the bar and comes unhinged. His emotional needs suffocate David, who takes out his frustrations on Giovanni, finding fault in his every move, in the filthy cluttered room he lives in, even mocking Giovanni’s appearance.

One afternoon, out of spite, he picks up an American girl named Sue and takes her to bed, using her almost violently, humiliating her. Afterward, he walks along the Seine, thinking of suicide. Then his fiancée, who bears the curious name Hella, finally returns to Paris. When she meets Giovanni she teases David about his “peculiar friends.” Feeling trapped, David decides to stay with her, turning his back on Giovanni and his homosexual past. The two decide to leave Paris and relocate to the south of France.

But it’s no good. In the end David loses both Giovanni and Hella. Despite opting for marriage in the future, with dreams of raising children, David can’t escape his other self. He goes on a bender, leaving Hella alone while he shacks up with some randy sailors he picks up in Nice. By the time Hella tracks down David to a seedy gay bar, with his arm around a drunken sailor, it’s too late for a revelation or a reunion. She leaves David just as he left Giovanni.

And what of Giovanni? Once betrayed by David, Giovanni descends into a spiral of despair, drinking heavily and using drugs, resorting to theft to make ends meet. He becomes Jacques’s kept boy, degrading himself further. Finally he kills his former employer, the bar owner Guillaume. He steals some cash and strangles him with the sash of his robe. Giovanni hides out on a barge until he is discovered. The state exacts its ultimate revenge. He is to be beheaded for his crime, executed by guillotine, a fate clearly echoing that of another outsider, Julien Sorel in Stendhal’s The Red and the Black.

The plot twists of Giovanni’s Room may seem a bit melodramatic to our modern sensibilities. But Baldwin wasn’t just going for Grand Guignol effects or playing the noir card. His story was grounded in fact. He was inspired by a figure he’d met in a bar in Paris, a handsome grifter with a dark, criminal past, who ended up committing murder and being executed for it. The guillotine was still prevalent in Paris when Baldwin wrote his novel and unbeknownst to me was still in use when I was living there in the mid-‘70s. It was finally banned in 1977.

Giovanni’s Room ends as it began. David is in the south of France, packing up to leave. He stands in front of a mirror, naked, examining himself. In a strange moment of self-awareness, he blames his body for his unhappiness. “And I look at my body, which is under sentence of death. It is lean, hard, and cold, the incarnation of a mystery.”

And while he imagines Giovanni far off in Paris being led to the guillotine, facing a door, beyond which “the knife is waiting,” David looks at his own body in a similar macabre light. “I look at my sex, my troubling sex,” he states, “and wonder how it can be redeemed, how I can save it from the knife.”

But at the very moment he imagines Giovanni is being slain, David steps away from the mirror, packs up his belongings and exits his house, tearing up a letter Jacques has written him about Giovanni.

He throws the pieces into the air, but a gust of wind causes some of them to fall back on him. He can’t escape the memory of Giovanni, nor what he did to him. We are left to assume David will return to America, to his former life, no doubt to start the dark cycle all over again.

. . .

Brooks Peters is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in numerous magazines, including Vanity Fair, OUT, the Village Voice, Opera News and Architectural Digest.