January 14, 2020 | By Tom Winchester

Through January 24

Ringling Museum

Details here

Sydney J. Solomon was one of the most influential artists in Sarasota’s history. His paintings were the first contemporary works to be collected by the Ringling Museum, his influence brought A-list artists and critics to Sarasota, and his house was one of the area’s most exciting architectural achievements.

A retrospective of his life’s work, now on view at the Ringling Museum titled, Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed, gives viewers a peek into his personal life and exhibits his masterworks.

Solomon grew up during a time when American art was dealing with an influx of European artists fleeing the World Wars. These European artists brought their ideas with them, especially their tastes for theories and practices from some of art’s most important movements. Impressionism, abstraction and Cubism were the dominant styles in Europe during the turn of the 20th century, and these styles began showing up in the United States throughout the following decades.

Solomon’s parents were Jewish immigrants from Austria and Hungary. He was born July 17, 1917, in Uniontown, Pennsylvania. He was precocious in the arts. He received a Technical Arts Certificate from Elmer Myers High School in 1935, went on to attend classes at the Art Institute of Chicago, and led an early career in graphic design and advertising.

During this period, Solomon was experimenting with impressionistic and abstract styles in his painting. Beehive Coke Ovens (1938) has the color palette and sensibility of a Monet, and The Artist’s Grandmother (1939) looks like something from Picasso’s ‘blue period.’ But this sensibility didn’t last very long.

Readers may be familiar with The Museum of Fine Arts,

St. Petersburg’s striking Westcoastalscape (1968), for many

years a showpiece in their permanent collection

. .

In 1941 Solomon enlisted in the army. This was arguably the most formative period during Solomon’s life, both in his personal style and his career. His roles in the army allowed him to expand on his artistic sensibility, delving further into abstraction – and ultimately caused him to end up in Sarasota, Florida.

His artistic career, though, to some degree, suffered from being in the army. Because he had enlisted, he wasn’t able to take part in the burgeoning wave of Abstract Expressionism that was coming into vogue in New York City and elsewhere.

During this time, Abstract Expressionism, which was informed by ex-pats from Europe, including those who fled the Bauhaus during Nazi Germany, began to take hold in New York City. This movement was directly paid for by the American taxpayer. Because of the Federal Art Project in August of 1935, which was funded by a program included in Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal called the Works Progress Administration, artists were paid $95 per month to create whatever they wanted.

For the first time, artists didn’t have to paint on the side. They were able to support themselves primarily by making art. This program was the catalyst for American Abstract Expressionism, and helped to bring this country in to the forefront of the art world.

As art critic Irving Sandler writes in his book, The Triumph of American Painting, “Many artists believed that the New Deal was inaugurating a cultural renaissance.”[1] Artists began making works that represent what many critics believe was this country’s first legitimate art movement. Artists like Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston, Willem De Kooning and Mark Rothko, although not all American, began successful careers creating Euro-inspired works that appealed to the American identity.

. . .

Solomon didn’t participate in the heyday of Abstract Expressionism. He spent the early 1940s designing camouflage, creating instructional pamphlets and writing newsletters for the army. He married Anne Cohen in 1941, helped to liberate the town of Roye, France in 1944, suffered frostbite during the Battle of the Bulge, was assigned to write and direct plays and entertainment for troops in Paris in 1945, and received an honorable discharge later that year.

Because of his lingering disabilities from having suffered frostbite, Solomon and his wife decided to move somewhere warm. They chose to Sarasota. “It was a little town of only 10,000 people, with its government offices down by the pier, but they had this beautiful Ringling Museum, with collections of European paintings and sculptures, real treasures, magnificent enough for any large city in the world.”[2] He became a student of the Ringling School of Art (now the Ringling College of Art and Design) on the G.I. Bill, bought a house, and in 1948 became a father to Michele Roye Solomon.

The 1950s brought a multitude of opportunities for Solomon’s career and his family. He became close friends with Ringling Museum director Chick Austin, began exhibiting regularly in New York City and in Florida, met Jackson Pollock while on vacation in the Hamptons, and welcomed son Michael in 1956.

It was also during this time that Solomon began experimenting with materials other than the classic oil paint and charcoal.

In the 1960s, Solomon founded the Institute of Fine Art at New College, the honors college of the Florida state university system, next door to the Ringling. Aesthetically, this decade brought about, in earnest, what can be considered Solomon’s signature style of painting. It was during this time that he shifted his materials toward acrylics and aerosols, and really began to differentiate his works from the oils of Euro-influenced Abstract Expressionism.

This style, in many ways, persisted for the rest of his life. George S. Bolge describes Solomon’s work during this time as having seemingly, “[F]reed itself from the patina of historical association…”[3] As compared to the black and gray, tightly formed gestures characteristic of American abstract painting at the time, Solomon’s gestures became larger, and his color palette became more vibrant.

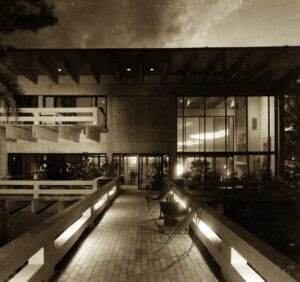

In 1970, Solomon built what is now an infamous house on Midnight Pass on Siesta Key. It was a poured-concrete, Bauhaus castle that served as his home and his studio. It was where he hosted parties for art world elite like John Chamberlain, Dan Flavin and Kurt Vonnegut, and found inspiration for his paintings.

But the house was built so close to the shore that it succumbed to the Gulf of Mexico in the mid-1980s.

This decade was also when Solomon created some of his most memorable artworks. Fifty-Fifty (1975) is a multi-layered square painting that is top-weighted by a swath of peach-colored paint. It’s bisected by a thick stripe of red, and layered sporadically with a translucent wash of sea-green.

Seakite (1976) resembles a window with sheer drapes. Its center is a seemingly luminous vertical rectangle surrounded by deep purples and blackish greens. Both pieces are indicative of Solomon’s signature style of large gestures, multi-layered coatings, and vibrant colors.

The Ringling Museum organized a solo exhibition of Solomon’s works in 1990 titled, Dialogue with Nature. Unfortunately, the last decade Solomon’s life was plagued by Alzheimer’s disease. He died on January 28, 2004 in Sarasota.

Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed at the Ringling Museum covers the artist’s entire life.

His personal photographs and letters are presented alongside his paintings, which gives viewers insight

into the person as well as the artist. The exhibition preserves Solomon’s legacy as one of Sarasota’s

most influential artists, and will introduce his work to a new generation.

ringling.org/events/syd-solomon-concealed-and-revealed

[1] Irving Sandler, The Triumph of American Painting:A History of Abstract Expressionism (New York: Harper & Row), 8.

[2] Gail Levin, “Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed” in Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed (Sarasota, FL: Artsentry Inc.), 14.

[3] George Bolge, “Syd Solomon” in Syd Solomon: Concealed and Revealed (Sarasota, FL: Artsentry Inc.), 31