By Tony Wong Palms

. . .

The Shape of Dreams

Through April 30

Dalí Museum

Details here

. . .

The planet reached a population milestone last year at 1:29 am, 15th November 2022, with the announcement of the 8 billionth human being born, in the Philippines. In recognition, the United Nations Population Fund tweeted – “8 billion hopes, 8 billion dreams, 8 billion possibilities. Our planet is now home to 8 billion people.”

Of course this is purely a symbolic gesture as it is quite impossible to track every single birth every single day. It is just as possible that the 8 billionth person was born in South America, or Europe, or anywhere else at some other moment in that particular day, or maybe even the day before – but point taken, this idea of the universality and inherent value of our hopes and dreams is once again confirmed.

While the United Nations tweet may refer more to the aspirational kind, since ancient times dreams in general have been a curious phenomenon, prompting a myriad of explanations, interpretations and a whole scientific field – oneirology – the study of dreams. And pertinent to this discussion, whether aspirational, day dreaming or in slumber, dreams have long been a source of inspiration for artists.

. . .

A masterful example is Dreams, a movie released in 1990 linking a series of vignettes based on director Akira Kurosawa’s own dreams and memories.

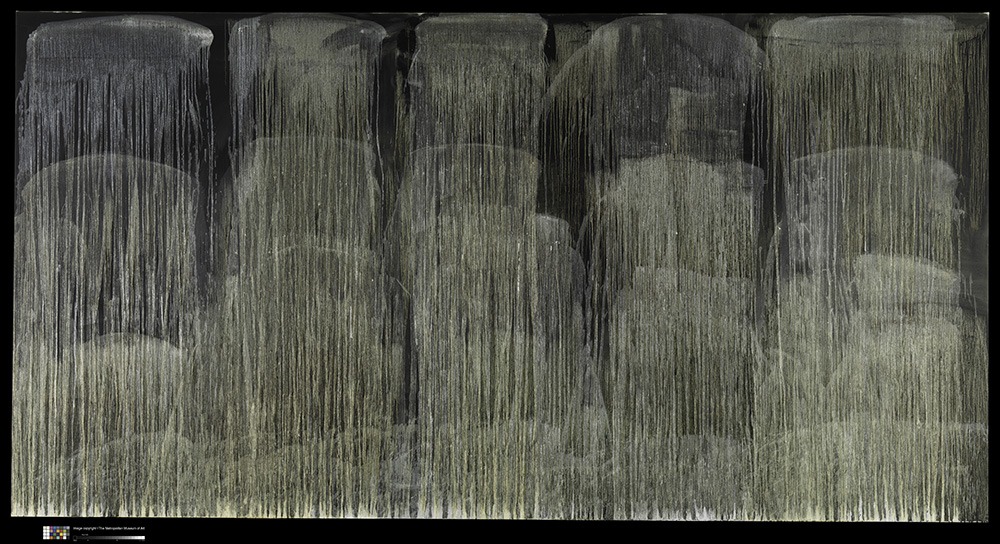

Coincidently that same year, the artist Pat Steir made a 78.5” x 151.1” painting titled, 16 Waterfalls of Dreams, Memories, and Sentiments.

This painting, in Steir’s signature broad drippy brushstrokes, is like looking through moist atmospheric conditions with its subdued tones of depth and mystery. Purchased by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) in 2009, the painting is now on loan to The Dalí Museum for their current exhibition – The Shape of Dreams.

Besides this loan from the MET, The Shape of Dreams also includes works from other prestigious institutions including the National Gallery of Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, The New Orleans Museum of Arts, St. Louis Art Museum, Hirshhorn Museum & Sculpture Garden, the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as the Dalí Museum’s own collection.

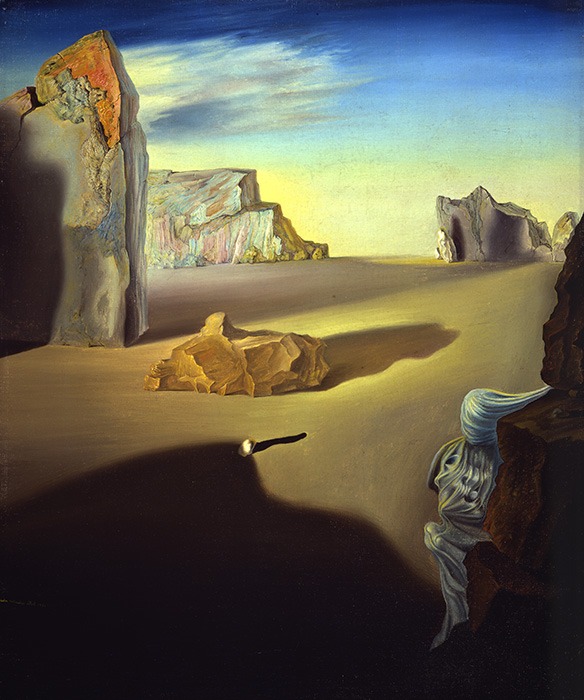

It is fitting that the Dalí Museum is hosting a dream exhibition as some of the best known artists in the recent century are Surrealists. Many are represented in the exhibition – Leonora Carrington, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, René Magritte, and of course the museum’s namesake, Salvador Dalí – where they bring forth dreamscapes of the unconscious.

The works, spanning 500 years from the 16th to the 20th century of Western art history, are organized into five overlapping themes – Source of Dreams, Nature of Dreams, Art as Dreaming, Visions and Nightmares and Use of Dreams.

The title wall, greeting visitors as they enter the gallery, is a floor to ceiling reproduction of the painting Selene and Endymion (48” x 66.5” actual size) by Nicolas Poussin during the Baroque period, showing the affair between the sleeping shepherd Endymion, in a dream liaison with the Greek Moon goddess Selene, as the winged figure Day begins drawing the curtain separating night and day with sun god Apollo in his chariot rising in the background.

This particular Greek/Roman mythology was a popular subject, launching a whole library of paintings and other works through several art periods between the 1600-1800’s. Diana and Endymion by Luca Giordano, c.1675-1680, where Diana is the Roman Moon goddess is another example in the exhibition.

At the beginning of a tour of the exhibition on opening day, Dalí’s Executive Director Dr. Hank Hine, curator of the exhibition, quotes Argentine writer and poet, Jorge Luis Borges – “Dreams retold are our first aesthetic act because we have to reorder them, like an artist reorders things in order to convey it…”

With this visitors are plunged into the Source of Dreams portion of the exhibition, a pathway of texts guiding visitors from one dreamscape to the next.

Because this exhibition sources from western art archives only, many of the works and stories told are of Greek, Roman and Christian myth origin, while other subjects range beyond those cultural borders.

One good example is Odilon Redon’s The Dream of Butterflies, 1910-1915, a 24” x 37.25” oil on canvas of butterflies floating over a mysterious background, which from the didactic label “… We feel for a moment transposed from ourselves, seeing perhaps as a butterfly sees.”

Parallel this with that of the Daoist, Zhuangzi (4th century BCE) who once fell asleep and dreamed he was a butterfly. Upon waking, he genuinely queried whether he dreamt he was a butterfly, or was a butterfly now dreaming of being a man.

This Daoist dream has inspired many early Chinese, and even contemporary artists with their interpretive works. And the famed Japanese poet, Basho, penned this haiku –

. . .

君や蝶我や荘子が夢心

you’re the butterfly

I’m Chuang-tzu’s

Dream essence

. . .

In the tour, Dr. Hank Hine continues, “When you do show five centuries of work you start seeing recurring motifs…”

One repeating motif is the iconic ladder or some similar ascending devise like Led Zeppelin’s stairway. There’s a ladder in Joan Miró’s painting Dog Barking at the Moon. Domenico Feti and Giorgio Vasari both did their version of Jacob’s Dream with their interpretation of the ladder/stairway. Max Beckmann has a ladder in his claustrophobic The Dream, painted after the devastating World War I. An upward aiming path narrows into a vanishing point in Kurt Selligmann’s Magnetic Mountain. Segmented lines and particularly the long vertical section become a ladder in Wilfredo Lam’s The Dream. And Dalí’s broken stairway winds up in The Broken Bridge and the Dream.

The exhibition designer even suspended a ladder from the ceiling, theatrically turning the gallery into a surreal space.

Because of the expansive story this exhibition was reaching, it’s understandable some works the Dalí wanted to include were unable to be borrowed – sometimes due to a work’s fragility, scheduling conflicts or the countless other reasons museums must consider before making works available for loan.

In each case, the painting in question was reproduced and framed in fashion so visitors can understand its status. This treatment does not distract or subtract from the curation nor the quality of the viewer experience, and may even provide another avenue of query and education for visitors.

Frida Kahlo’s Tunas (Still Life with Prickly Pear Fruit), 1938, 7.75” x 9.75” oil on tin painting, illustrates the long and winding road of this loan process the Dalí Museum went through when pulling this exhibition together.

The Dalí’s team had already installed the reproduction of this painting readying for opening day when newsflash! – the loan was ultimately approved and the painting shipped and arrived the day before Dr. Hine began his welcoming tour.

It’s really an exquisite painting showing three stages of this prickly pear fruit on a plate. The didactic label beautifully states – “This painting arises from the tendency of dreams to combine and alter the appearance of objects and persons…

“… Dream, like art, has this power to unmask the hidden nature of things.”

The Dalí Museum set up two other galleries augmenting the exhibition. One is dedicated to literary pathways into the understanding of dreams with a display of books from authors ranging from Shakespeare to Freud to Joseph Campbell.

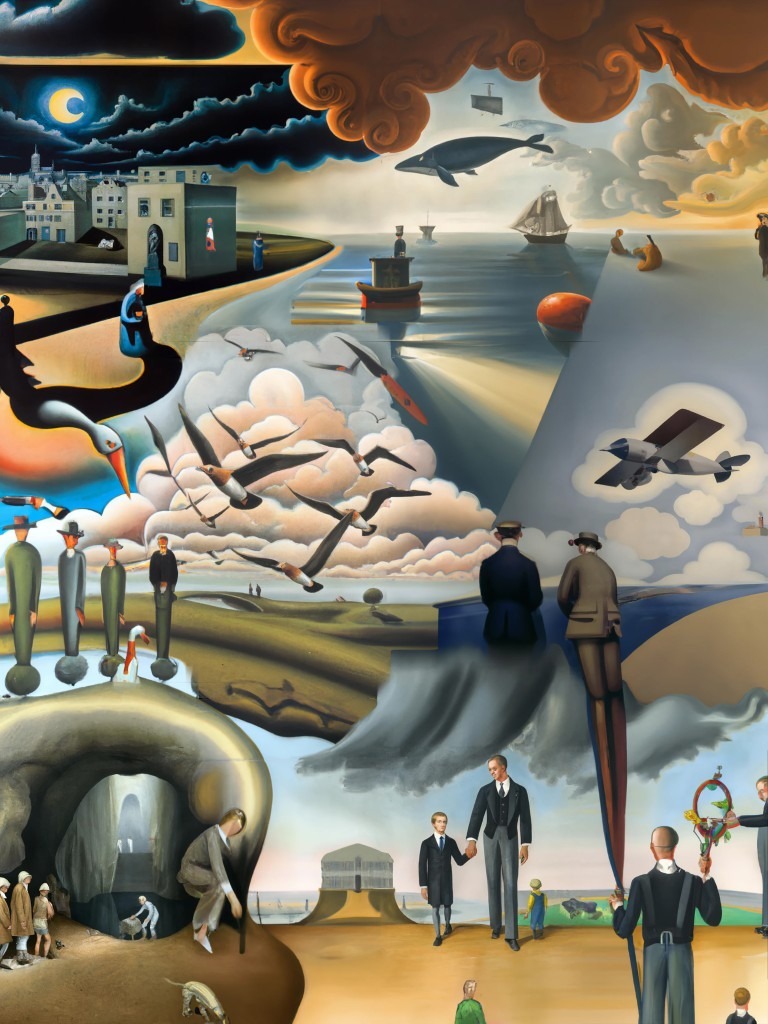

In the second gallery is an interactive project called Dream Tapestry. Using an artificial intelligence program named DALL-E, visitors can input their dreams, individually or as a group, and DALL-E will select images fitting to those dreams, weave them together into one montage picture – some even in style of paintings in the exhibition – that is projected onto the gallery wall.

Visitors can download their image as a keepsake, and all of these dream paintings can be seen on this page.

Of the many words and quotes hidden in the pages of the literary gallery, here’s one from Joseph Campbell – “Myths are public dreams, dreams are private myths.”

So the potential of any dream – including daydreams as illustrated in Philip Guston’s Daydreams, 1970, 72.1” x 80.1” oil on linen painting, this exhibition brings together the public and the private, joining the long human parade with Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, the whole of Aboriginal Dreamtime, the Hindu God of Brahma who dreamt this whole universe into existence… exploring a bit more of who or what we are through the intimacy of dreams.

. . .

thedali.org

. .

. .