Meeting Curatorial Challenges

Curator as Mediator

by DANNY OLDA

Though making no art, a curator has a special, even creative hand in art developing exhibitions.

Works of art bear their respective loads of signification. It’s what art “does.” However, there is also meaning that exists, not in each individual work of art, but stretched in the relationships between them.

It congeals as an exhibition takes shape and evaporates as it is dismantled. The value of a well-curated exhibition is greater than the sum of its individual pieces and its ideas weightier together than apart. If contemporary art curating were a physical field, this ephemeral added value and rhizomatic meaning would be its boson, lending mass and slowing down the art traveling through it.

This activity of putting meaning into and pulling meaning out of artworks through exhibitions can empower museums to take an active and pedagogical role provoking dialogue. The role of museums can be more than an ornate storage chamber as it becomes an active civil forum. The curator, beyond serving as a steward of cultural artifacts, can provide a creative and critical role

“A curator not only serves to take care of artworks and their presentation, but also acts as a mediator between audience and artist,” says Katherine Pill, curator of contemporary art at the Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg.

As with mediators of any sort, the role can be a challenging one that involves finding elusive equilibriums.

I’ve always believed that museums are safe spaces for difficult conversations. They’re civic spaces and should allow for reflection on our past as well as our present

“I’ve always believed that museums are safe spaces for difficult conversations. They’re civic spaces and should allow for reflection on our past as well as our present,” Pill continues. “That’s not to say, however, that pleasure and beauty aren’t driving forces for museum visits. It’s important to find a balance.”

Noel Smith, the deputy director and curator of Latin American and Caribbean Art at the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum, characterizes contemporary museum curation similarly. She says, “As museum professionals, our job is to challenge artists, audiences and ourselves, to present ideas, themes and work that lead us to question ourselves and our conceptions about others.”

This all hints at the complex social intersection in which many curators are situated. They often find themselves, not only as mediators between artists and audiences, but also liaisons between their respective institutions and the public, as well as parsers in theory, praxis, aesthetics, concepts and more. Enticing audiences to visit and return repeatedly to the museum while also fostering spaces for “difficult conversations” and being unafraid to “challenge…audiences” is an ambitious if not precarious balance indeed.

“The real challenge is to combine ideas with aesthetic enjoyment, and I think if you have that, you’re going to draw satisfied viewers,” says Smith.

This challenge has been accepted by these curators and their museums, but how is it being faced? How can museums and their curators encourage audience engagement and interaction while maintaining arts excellence and rigor?

With the words “public” and “social” in her title, Sarah Howard is perhaps especially concerned with audience engagement as a curator. As the curator of public art and social practice at the USF CAM, Howard feels that a certain linchpin to meaningful audience engagement is also its own reward.

“Collaboration is a key component to both our work within the museum and essential to our partnerships which extend beyond the museum,” Howard says.

These collaborations and partnerships extend outward from the Contemporary Art Museum, the curators, artists and into the community. Howard says this often involves student organizations, cultural partners or communities relevant to a specific exhibition. Notably, these collaborations are not perfunctory or empty gestures to drum up audience buy-in but are genuinely creative engagements.

“This type of engagement has included visual art, spoken word, dance and musical compositions and performances in response to the exhibitions,” Howard says, “as well as lectures and panels which explore exhibition concepts through different fields of inquiry.”

These collaborations not only generate new audiences, but also innovative thinking by way of diverse perspectives.

“The results of these partnerships are the most rewarding,” she continues, “as they stimulate new ideas and methods for direct engagement with the museum, tap into new audiences and peer groups and provide opportunities for long term growth and development between these communities and the museum.”

Noel Smith and the USF CAM know their audiences well. She’s also aware of the countless sources of information and thought, both within and beyond contemporary art, vying for their audiences’ attention.

“There are many artistic voices today involved in vital issues in the world affecting students and their families, and we try to find those voices that can speak clearly and urgently to them, while never lowering our standards of excellence,” Smith explains. “We try to lead them to the understanding that contemporary art and artists have a real role in the world today.”

For example, in June and July 2017, USF CAM presented the exhibition Woke!, featuring the work of artists William Villalongo and Mark Thomas Gibson. As shocking and increasingly visible instances of police violence against black bodies repeatedly unfolded across the nation and the Black Lives Matter movement grew in response, the practices of these two artists were affected as well. Beyond the hyper-relevant slang title of the exhibition, the work of the exhibition spoke to extremely timely and important issues as well as highlighted two personal artistic responses to socio-political contexts that the University students were also living through.

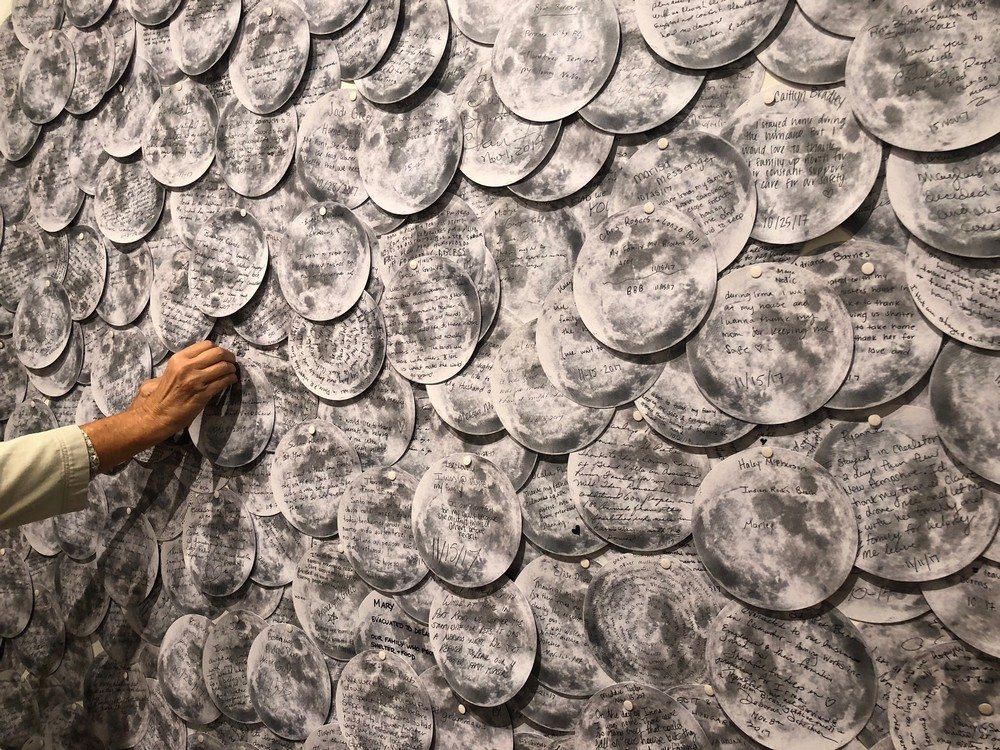

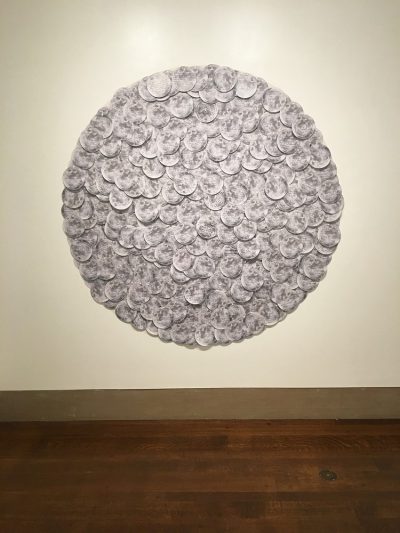

Another strategy in simultaneously attracting and challenging audiences is featuring artwork that engages viewers in very literal and active ways. Pill relates a recent exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Mickett-Stackhouse: Confluence.

“We had the honor of working with Carol Mickett and Robert Stackhouse recently, and they activated our Lee Malone Gallery in an unprecedented way,” she says. “The artists were in the gallery twice a week, engaging with visitors. Robert said, ‘It was an instant engagement; the art starts talking to them instead of being quiet on the wall.’ I love the idea of participatory art, and of audience interaction with the artists.”

The real challenge is to combine ideas with aesthetic enjoyment, and I think if you have that, you’re going to draw satisfied viewers

Pill and the museum further explored participatory art through an installation by Fluxus artist Alison Knowles, a founding member of the group known for it’s playful, irreverent and interactive artwork. For her installation Bean Garden (1976/2017), a wooden box is filled with about 2,500 pounds of great northern beans and fitted with contact microphones. Visitors were invited to walk through the pool of beans, the sound of treading beans amplified throughout the museum gallery.

“That was an adventure for the Museum, in terms of both logistics and safety concerns, and of presenting a Fluxus artwork made of everyday materials that some questioned as being ‘art,’” Pill says. “That, of course, played very well into larger conversations regarding elitism in the art world and thinking about who gets to make designations of ‘fine art’ and why.”

This conversation of elitism in the art world, gatekeeping, inclusion and exclusion is an expansive and robust conversation in the world of visual arts—it’s a tension that has produced a lot of notable artwork during the last several decades. However, that conversation tips politically to a troubling degree for many working in the arts during a time of populism characterized by intense anti-elitist attitudes coupled with anti-intellectualism marked by a severe wariness of academic exercises. In such an environment, does the curatorial challenge of simultaneously attracting, engaging and challenging audiences become more complicated?

Howard, for example, recognizes that many academic and cultural institutions are currently facing a backlash that is an expression of populist and anti-intellectual beliefs which can include significant budget cuts and loss of grant funding. However, she also sees an opportunity in the moment.

“While we consider socio-political and ethical context with any program, as a museum at a higher education institution I believe we have a critical role in presenting work supporting ideals and values associated with democratic pluralism, promoting equality and diversity, creating space for empowering dialogue and debate and directly responding to our contemporary cultural moment through thoughtful and provocative exhibitions and programming,” she says.

These thoughts are reflected by Smith as well.

“If anything, this socio-political context has deepened my resolve to bring art and artists to campus that challenge the xenophobia, misunderstanding, fear, intolerance and hatred that are often part and parcel of populism and anti-intellectualism,” Smith says. “We are charged with forming students into global citizens, and that means introducing them to diverse peoples, thought systems, ways of living, religions, etc., and in this way encouraging them to develop a coherent system of ethics in dealing with the world that embraces tolerance and cooperation, not hatred and fear.”

During the last century or so, the role of the museum curator has broadened and become increasingly complex, continually meeting with new challenges. Political turmoil as it exists and is likely to come, will certainly pose further challenges. However, this group of local museum curators may provide a point of optimism and perhaps even some excitement, as they seemed poised to face the complexities of contemporary curating while constructively engaging artists and audiences alike.