By Danny Olda

Defining Lines

The Prints and Drawings of Maxime Lalanne

. . .

Through July 17

Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg

Details here

. . .

There are no maybes in etching.

There are literally no gray areas. Each stroke is either made or not made – there is only ink or bare paper.

When done well, this confidence belied by its often muted palette and nuanced subject matter makes etching an especially graceful artform. Many of the prints and drawings of Maxime Lalanne, currently exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg through July 17, are no exception.

The exhibition, titled Defining Lines features prints and drawings from Maxime Lalanne’s career, which stretched from 1850 until his death in 1886. Thanks to a gift from the author of The Complete Prints of Maxime Lalanne, Jeffrey M. Villet, this museum now holds one of the world’s largest collections of the artist’s work.

. . .

. . .

Nearly 140 year later, it’s clear to see in Lalanne a man who loved to draw. Defining Lines shows this through the sheer number of his works and his desire to teach his craft. Lalanne died still holding charcoal in his hand, in the middle of a drawing.

Some of the work is deeply felt, some is visually beautiful, while some undoubtedly exist for the simple pleasure of putting charcoal to paper.

Through his etching and drawing, Lalanne’s 19th century Paris and Bordeaux emerge clearly felt and seen. The artist sinks a real place in time into the paper.

. . .

. . .

Lalanne’s prolific career took place during a time marked by socio-political unrest in his home of France and warfare through Europe at large. Inklings of this world unfolding around Lalanne can be found in subtle but fascinating clues in his work.

For example, the small etching An Effect of the Bombardment, State I (1871) was created at the end of the Franco Prussian war and inevitably calls to mind current images of European conflict. In the etching, a bombed-out house stands hollow, eerily yet fittingly resembling a sun-bleached skull.

However, with a closer look at the little work of art, a tiny hot air balloon can be seen hanging in the distance, high in the sky. Seemingly hopeful, floating gently in the background, the balloon would’ve also been seen as a tool of warfare to Lalanne, an important reconnaissance vehicle during the brutal siege of his beloved city of Paris.

Captivating details such as these wait for observant viewers in each drawing and etching.

. . .

. . .

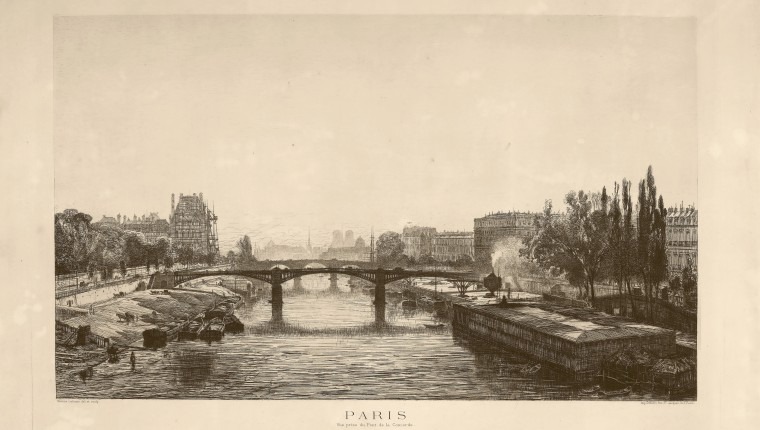

Lalanne captures Paris in a time of political revolution, artistic revolution, war and modernization as well as times of tranquility and quiet. The etching Paris, View from the Concorde Bridge State IV (1866) is a straightforward scene of the city on the Seine river. However, Lalanne does things that should seemingly be impossible with the stark lines of etching.

To create these etchings, Lalanne would’ve scratched lines onto the surface of a metal plate before they were eaten away with acid and used to create a print much like a stamp. Yet, fog or smog hangs in the distance, shrouding the skyline while mist rises off the river, softening the reflection of a bridge on the water.

A much more dramatic view of the same city is found in his drawing Paris on Fire (c. 1871). The view seems to be exactly the same, however now the city is engulfed in flames and drowning in smoke, during a time of civil unrest and revolution.

By this point in his career, Lalanne was primarily making his art by etching. However, he chose to depict this particular scene by drawing, significantly, in charcoal. It’s as if the city is not only depicted in the drawing but the drawing is made out of the smoldering city itself. Lalanne’s charcoal strokes give a visceral feeling to the drawing of Paris on fire.

. . .

. . .

While Lalanne’s work was well-liked in his time and contributed to a renewed interest in etching, it’s easy to imagine how it seemed as if etching was being crowded out. Lalanne was born the year that the first camera photograph was taken and it increasingly became the preferred means of documenting events and places. At the same time, his artistic peak happened during an important artistic revolution that he largely abstained from. Lalanne stayed true to his artform.

When considering late 19th century French art, we more readily grasp for the Impressionists. While Lalanne holds steady with his love of drawing, etching and faithfully capturing places, what may or may not be a touch of the artistic zeitgeist is found in the etching Sunset, State II (1881).

Based on a painting by Charles Francois Daubigny, the etching depicts a peaceful scene with a dramatic late-day sky. The sky roils in hundreds upon hundreds of lines like turbulent water, not only calling to mind Lalanne’s contemporaries, the Impressionists, but the post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh that would arrive after his death. The sky is mesmerizing as Lalanne uses only black lines to conjure movement, drama and even sunset color.

. . .

. . .

Defining Lines and the artwork of Maxime Lalanne is often quiet and small, but it beckons viewers to step in close and search the work.

His art seems straightforward but will reward you with surprising details. It will draw you into a Paris a century and a half gone and an artist’s sincere love of his craft.

. . .

. . .