Being an avid user of our library system, I often find myself led to unexpected literary treasures. In a quest for William Morris’s ‘How We Live and How We Might Live,’ the catalog system suggested ‘A Natural History of the Future’ by Rob Dunn as an alternative. Intrigued by the title and description, I checked it out, and its exploration of ecological laws and the inherent risks of relying on human-controlled environments has stuck with me ever since.

One particular chapter talks about the inherent risk of monoculture agriculture, a process driven to its extremes by capitalism. Although agriculture has been a cornerstone of human civilization for millennia, our contemporary approach to farming represents an unprecedented level of control and manipulation. In the relentless pursuit of efficiency and profitability, we have industrialized food production to an extent where crops are meticulously edited and controlled for optimal yield under carefully managed conditions. However, like every other anthropocentric system, this approach proves to be unsustainable.

The current era of capitalism, marked by its relentless pursuit of profit, contributes to the exacerbation of climate change. As our climate becomes more extreme, the inherent risks associated with monocropping—our predominant method of cultivation—become increasingly apparent. Monocropping leaves our food supply vulnerable to the unpredictable forces of nature, such as floods, droughts, and pests, due to the lack of biodiversity that would otherwise enhance resilience. The higher cost associated with cultivating diverse crops stands in contrast to the cost-cutting principles of late-stage capitalism, denying the priceless value of the ecosystems we rely on.

This vulnerability is not merely a theoretical concern; it poses a tangible threat to our food security. A lack of crop diversity, while economically expedient in the short term, leaves us ill-equipped to face the challenges presented by a changing climate. Corporations, in their pursuit of profit, contribute to creating a precarious situation by relying on human-controlled environments, ignoring that nature persistently forges ahead, defying our attempts to restrain it and, in the end, triumphantly breaking through our every effort to contain it.

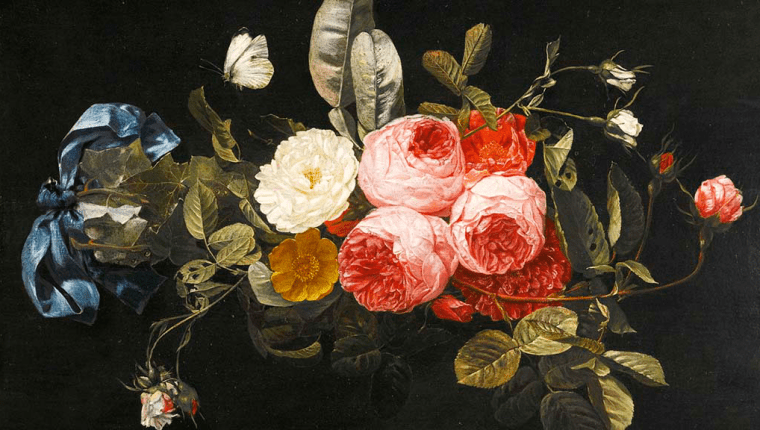

This inspiration led me to create Weeding, drawing upon elements from Dutch still life symbolism. Blue ribbons, emblematic of luxury and wealth during that era, served as status symbols, intricately linked with expensive and fashionable clothing. Their presence in still life paintings elevated the depicted objects, conveying their value and desirability. Flowers, particularly lilies, commonly featured in still life setups, symbolized the transient nature of life and the inevitability of death. To bring this vision to life, I constructed my own still life, photographed it as a drawing reference, and ultimately created the final piece—with many thanks to the library for being the catalyst!