November 24, 2020 | By Jennifer Ring

It’s the last week to see Copper, Silver, Salt, Ink –

The Chemistry of Photography’s Enduring Desires

Through November 29

Museum of Fine Arts

Details here

The Museum of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg started collecting photography in the 1960s, long before most museums considered photography a gallery-worthy art form.

Fifty years and 17,000 images later, the MFA now has one of the largest photography collections in the Southeastern United States. This is part of what attracted Dr. Allison Moore, the MFA’s new Curator of Photography, to the museum in December 2019. Moore’s job is to study photos in the collection and present them in a way that tells the story of photography.

“It’s an amazing collection,” Moore told Creative Pinellas. “It has a wonderful selection of major 20th-century artists and photographers, and then it also has 19th-century work in it. I also love that the collection is huge — it has all kinds of medium and processes.”

What’s even more impressive is that the bulk of the collection came from a single donor — Dr. Robert Drapkin of Clearwater FL.

Drapkin started collecting photographs in New York City in the 1970s, just as early 19th century photographs were beginning to hit the market. “Prior to the 1970s, there wasn’t much interest in showing these photographs,” says Moore. “To show them as art framed in a gallery was something new.”

In 2009-2010, Drapkin’s friends Bruce and Ludmila Dandrew, also from Clearwater, purchased thousands of Drapkin’s photos and donated them to the MFA. In a Tampa Bay Times article on the acquisition, Lennie Bennett noted that it would likely take decades for the MFA to show all the work.

The MFA introduced the Dandrew-Drapkin collection to the public in 2011 with the exhibition Familiar and Fantastic: Photographs from the Dandrew-Drapkin Donation.

The 15,000-item collection stole the spotlight once again in 2015 when the MFA celebrated its 50th anniversary with Five Decades of Photography at the Museum of Fine Arts. Bennett called the 300-item exhibition “a comprehensive study of the medium in all its forms.”

And while Bennett was impressed by the comprehensive nature of the MFA’s photography collection, this wasn’t all of Drapkin’s photos. When Moore came to the MFA, Drapkin mentioned that he had these additional photos.

“Naturally, I wanted to see them,” says Moore. “We had some conversations about possibly exhibiting them because they are so rare and fabulous and it would be a great opportunity to really have a historical show.”

This is what yielded the MFA’s Copper, Silver, Salt, Ink: The Chemistry of Photography’s Enduring Desires exhibition, on display at the MFA through November 29.

It’s a rare opportunity to see photographs from the inventors of the medium, William Henry Fox Talbot and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, and its earliest adopters.

Talbot and Daguerre developed competing photographic processes around 1840. They both took advantage of the fact that silver salts react with light to form an image, but in slightly different ways. Daguerre’s “film” was a copper plate coated with silver and exposed to iodine to form silver iodide.

Daguerre loaded the plate into his camera like film before taking a photo. As the light entered the camera, the silver salt darkened, forming a unique, highly-detailed image on the plate that couldn’t be reproduced.

Talbot coated paper instead of copper with silver iodide to create his calotypes, which he reproduced by placing another piece of paper on top of the negative and exposing it to light to create a positive image.

At the MFA you can see calotypes Talbot took of his daughter, the tomb of Sir Walter Scott and the Boulevards of Paris in the 1840s, along with an actual calotype camera.

But calotypes gave us so much more than that and so does this exhibition. In the hands of European photographers like Bisson Frères, Charles Marville, Maxime Du Camp, Gustave Le Gray, Auguste Salzmann, Robert Macpherson and Linnaeus Tripe, calotypes documented the world’s monuments, architecture and landscapes as they were in the 1850s. In the hands of Roger Fenton, calotypes gave us the first war photography.

Bisson Frères’ and Charles Marville’s photographs of Notre Dame, Maxime Du Camp’s photos of the Middle East, Linnaeus Tripe’s photos of French colonial India, and Auguste Salzmann and James Robertson’s photos of Jerusalem all serve as potent reminders of photography’s relationship with history. You can see examples of all of these in Copper, Silver, Salt, Ink.

While European landscape and travel photographers preferred calotypes, the detailed nature of daguerreotypes made them extremely popular for portraiture, especially in America.

“Once the daguerreotype was invented and offered to the public in France in 1839, portrait studios opened immediately and started to move all around the world,” says Moore. “The thing about the daguerreotype is that it’s really detailed. If you look at it with a magnifying glass, you will see more details rather than less. It’s really cool…

“They’re unique images. They are not reproducible. The calotype has reproduction in its favor, even though they tended to fade. But both processes were basically over by the 1860s. The daguerreotype gave way to the tintype and the ambrotype, which were cheaper processes…and the paper negative was replaced by the albumen print.”

Daguerre’s influence is seen through the eyes of the many portrait studio photographers in America who utilized his technique. The list includes family photos, John Adams Whipple’s daguerreotype of the Moon, and Southworth & Hawes’ portrait of Daniel Webster.

Next to all the calotypes and daguerreotypes, I was drawn to two images in the gallery that look quite different from the others. These were Talbot’s photoglyphic engravings, completed in the late 1850s. The lesser-known art form combines photography with printmaking to create what ends up looking like a finely-detailed, photorealistic ink drawing. Talbot, disappointed with his fading calotypes, invented this process later in life.

The two engravings really brought the show together for Moore. “Those two works, which I hadn’t seen before, tell a lesser-known history,” says Moore. “And that became the hinge from the earlier photographic processes to the contemporary 20th-century photogravures.”

Photogravures achieved popularity in the early 1900s. George Eastman had just produced the first rolls of film and introduced the first Kodak cameras to the public in 1888. As more people bought cameras and took photos, artists started creating artistic prints using photogravure to distinguish themselves from the amateurs.

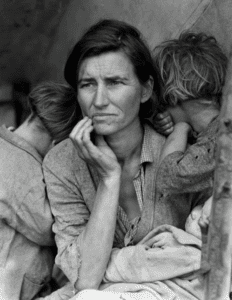

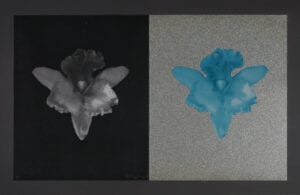

Copper, Silver, Salt, Ink’s photogravures span a century, from the pictorialists of the early 1900s to Depression-era photographers working for the Farm Security Administration between 1935 and 1944 to GraphicStudio’s photogravure revival in the 1970s to present day.

“I love the contemporary photogravures,” Moore told Creative Pinellas. “I love that they tell a story from 1900 up to 2016.”

When I first walked through Copper, Silver, Salt, Ink: The Chemistry of Photography’s Enduring Desires with the MFA’s Curator of Contemporary Art, Katherine Pill, she told me how much this exhibit reminds her of her Photography 101 class in college.

The history of photography hangs on the walls of the MFA. Drapkin’s collection of photos tells stories of humanity and invention that will never get old. I look forward to seeing more of them in the future.