October 4, 2019 | By Julie Garisto

Kirk Ke Wang’s 2019 Biennal Takeaways

Observations on the groundbreaking art and events of the Whitney and Venice Biennials of 2019 from one of Tampa Bay’s most beloved and prominent contemporary artists

Artist Kirk Ke Wang is an intrepid inspiration-seeker. Even when he’s working day and night in his Tampa studio, he finds time to support fellow artists’ new exhibitions. At art shows, he greets you cheerfully, but an idea might grab him a little longer than the brief constraints of small talk. He’s in the moment with his discoveries and his enthusiasm is infectious. Eloquent and captivating, he’s always happy to share how new ideas are informing his works, and is equally interested in others’ observations.

Kirk ke Wang’s Sugar Bomb installation at HCC-Ybor, 2013. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The Chinese-born artist holds two MFAs, has a wife and two daughters, a co-op in Manhattan, a home in Shanghai, a nonprofit Tampa studio and a tenured professor position at Eckerd College. His past works feature convergences of social consciousness and child’s play (toys, candy, cartoon characters). His installation Sugar Bomb challenged viewers by depicting lethal weapons — war missiles — with bright-colored candy.

The piece at Hillsborough Community College – Ybor made “serious comedy out of political encroachment” according to art critic Megan Voeller and comprised more than 30 bombs, each handmade by the artist from Chinese, Cuban and American found objects, which hung from the gallery ceiling. Gummy bears, Skittles and Cuban sugar filled the missiles, inviting the viewer to consider how people are seduced into consuming and how culture can be as invasive as missiles.

In 2015, his memorable solo show Yes & No dealt with the dichotomy of the opposites in his life, at Opera Central, St. Petersburg Opera’s downtown annex. Among the large-scale works was a collaboration with Theo Wujcik titled … and Chained Bird, a tribute to famous Chinese contemporary Ai Wei Wei, whose passport was revoked from 2011 to 2015, the time period in which the boldly optimistic painting was conceived. The painting features on the left side a pixel representation of Ai and on the right, a shackled bird that’s looking up to the sky, hinting at a hope for freedom.

A committed lifetime learner, the 57-year-old contemporary artist travels throughout the year, and his creative wheels keep turning long after he stops at a new city or exhibition, absorbing new ways to approach concepts and materials. In his paintings, illustrations and installations, Wang explores dichotomies around immigrant identity and other compelling and relevant topics.

Perpetually experimenting, Wang has demonstrated via social media posts that he’s also a tireless navigator of the art world. This year, Wang visited two major events that take place every other year — the Whitney and Venice biennales.

The Whitney Biennial, an exhibition of contemporary American art, usually features young, emerging artists at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. The event spans six months and began as an annual exhibition in 1932, before becoming a biennial exhibition in 1973.

One of the world’s biggest art happenings, La Biennale di Venezia also takes place odd-numbered years in Venice, Italy — and began almost 125 years ago as a forum to promote contemporary art.

We at the Arts Coast Journal were pretty envious about Wang making it to both of the prestigious international events and asked him to share his thoughts on the experience. He starts by telling us that he takes joy in seeing artists experiment with subjects he’s working out himself.

“The biennial artists confirm the direction of my endeavor, which reinforces my confidence, but to the opposite. I try to stay away from them in terms of styles, methods or genres. What inspires me most are their attitudes, philosophies and life experiences.”

Which artist made a big impression?

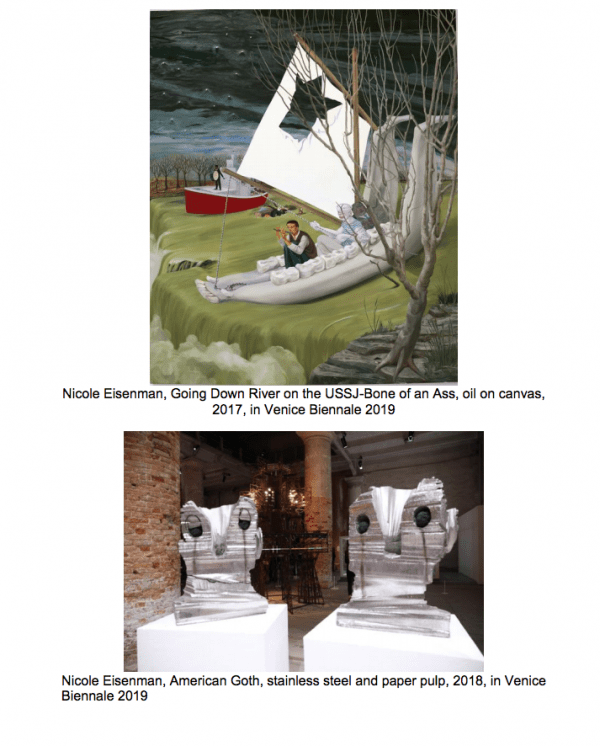

Nicole Eisenman, one of my favorite artists, was featured in both the Venice Biennale and Whitney Biennial this year. How many artists could have such honor?!… Though my work is very different from hers, I have been following Eisenman for years and am inspired by her prominence in the art scene nowadays. I am attracted to her peculiar, idiosyncratic depictions of her ecosphere through paintings, sculptures and installations.

Eisenman’s work reverberates between the historical and present, the public and private, the irony and the sincerity, which resonates with the way I comprehend and create art. In my recent series titled Human Skins I try to intertwine a concurrence between conventional iconography and contemporary impertinence. I am inspired by Eisenman’s drawing on allegorical allusions to evince a steadfast commitment to the details of our habituation, chaotically in my case. She encouraged me to enjoy the solitude of being an outlier.

What was one major difference in mood, audience or theme between the events?

There are many reviews about this year’s two major biennials on public media. However, to me, the major difference between the Venice Biennale and Whitney Biennial was the attitudes of curating.

The British curator Ralph Rugoff of Venice Biennale 2019 crafted a platform for artists around the world to showcase their talents, while nations competed in their pavilions to address the theme of this biennale: “May You Live in Interesting Times.” Mr. Rugoff curated an exhibition that was comprehensive, inclusive and egalitarian.

The curatorial team of the Whitney Biennial 2019, Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley, had a different agenda —fostering the inclusiveness of minority artists in national biennials. I think they succeeded, as 40 percent of the artists selected in this Whitney Biennial are minorities.

However, while congratulating their success of promoting diversity, I am a little disappointed to see less Asian American artists were included this year, comparing with previous Whitney biennials. I think it would miss its goal of promoting equality, if we were more in favor of the larger minority groups than those politically weaker ones.

Different from the relaxed and peaceful atmosphere at the Venice Biennale, the Whitney Biennial permeated with political confrontations. Further than the controversial sensation caused by Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket in 2017, this year’s biennial met its crisis.

Eight and more participating artists announced withdrawing from the exhibition to protest Whitney’s vice chairman of the board Warren Kanders, due to his ownership of companies that manufacture tear gas and other weapons for the police and military, including tear gas that has been used at the U.S. border against migrants and during protests in Ferguson, Missouri. This year’s Whitney biennial would be a third empty, if the demand were not met. Walkouts and withdrawals have happened before, but a deserted show is beyond precedent.

What would you tell your students about the importance of attending the biennal?

Go to see, to feel, to sense and to touch the pulse of the contemporary art world. To learn the methodologies of those creative individuals and consult their paths of success. But never try to copy what is fashionable and popular, and to repeat what has already been done.

Who were your other standout artists in each festival?

There are many great artists in the biennials and I liked their works in different ways. Besides Eisenman, the most standout artists to me in the Venice Biennale 2019 are:

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, a team artist whose works often involve the staging of visceral, intimidating spectacles. They created the industrial robot that turns and flexes restlessly in a transparent cage to collect and control “blood” in the venue of Giardini. They called it Can’t Help Myself. It reminds us of the recent history of China and current protests in Hong Kong.

They also created another equally standout work at the Arsenal. Titled Dear, the installation includes a while silicon chair behind a Plexiglas barrier, like the imperial Roman chair featured as a component of the statue at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC. The chair is kept company by a rubber hose that violently whips around the surrounding space in response to blasts of highly pressurized air. Is it a metaphor to the current presidency of the United States or China, or both?

There are many outstanding national pavilions in Venice Biennale as well. If I have to pick one, I would pick the Belgian Pavilion. I enjoyed the irony, lightheartedness, innocence and banalness of the exhibition, with a slight bitter and sweet strangeness.

Titled Mondo Cane by artists Jos de Gruyter and Harald Thys, the Belgian pavilion featured an installation regarding the duality of human conditions. There is a group of automated puppets set amongst a series of large drawings of pastoral scenes and steel grids that fence off the pavilion’s lateral recesses. Some of these puppets are craftsmen – a musician, a shoemaker, a knife grinder, a spinner – who faithfully exercise their respective skills. It is a utopian world, pure and clean.

Around the edges is a parallel world filled with roguing zombies, poets, psychotics, and dropouts. These two realities coexist in the same space, but appear unaware of one another, signifying the segregation in both physical and mental worlds.

<

To me, the most standout artist in Whitney Biennial 2019, besides Nicole Eisenman, is an artist from LA, Ragen Moss. She created a series of hanging sculptures, translucent and floating, to explore the ideas of making space and forms inside other space and forms.

Her sculptures create tension between transparency and opacity, illumination and darkness, sculpted marks and painterly gestures, text and form, with contents sourced from literature and law (she is also a practicing lawyer). I adore her work greatly because we shared the same aesthetics and strategies when I did my Sugar Bomb project a few years ago.

What surprised you at either or both of the biennials?

The most surprising — or should I say shocking — work to me in Venice Biennale 2019 is the Japanese artist Mari Katayama. Her photographic-based works featuring herself surrounded by things she has made, including hand-sewn body doubles replicating her unique physique.

Born with a rare congenital disorder that affects the shin bones, she chose to have her legs amputated when she was nine. When she discovered the Japanese puppet theatre Bunraku, she photographed the puppeteer’s hands and printed them on fabric to make them as wearable soft sculptures. Her work that crosses between tentacle creatures and a cloak of invisibility in which arms and hands are everywhere, gives me chills and visceral reactions. Through her work, I see the beauty of fulfillment.

Another surprising work to me in Whitney Biennial 2019 are the new sculptures by Wangechi Mutu, an artist from Kenya who also lives in NYC. I am very familiar with her watercolor work, which combines human feature with images of wild animals and plants. Every semester, I introduce her work to my painting students when we discuss transparent paintings.

To my surprise in this exhibition, I saw her talent in sculpture. Mutu uses natural and manufactured materials merging with and emerging from one another, coalescing into larger-than life, earthy and android-like female forms. She radicalizes the clichéd associations of nature as an eternally forgiving female-mother, and expresses a deep sense of humankind’s complex, equal and non-negotiable nonexistence with one another and all organisms.

Tell us about what you have coming up.

I plan to exhibit my new works internationally, nationally and locally, like the one coming up at the Morean Art Center of St. Petersburg in January 2020.

While continuing my Human Skins series that I started for the Skyway contemporary art project at the Ringling Museum of Art in 2017, I am currently creating a series of mixed media and interactive works dealing with issues of immigration. I am also conducting a research project regarding the social conditions of Asian Americans in the local region, as well as in America at large.

As an artist from Asia and living in America for over 30 years, I am continuing to focus my art on issues that conflict my experiences with today’s mainstream typecasts, from the standpoint of a diaspora.

In my art practice, contents overrule forms and methods. I experiment with a wide range of media, from painting to sculpture, photography, video, conceptual, performance and installation art. Although oscillating between them, I intend to weave a tapestry of my vision of the world, led by a consistent thread: the fear of an inexorable cataclysm.