Florida’s Native Past

in Words and ImagesMarried couple Suzanne Williamson and John Capouya collaborate on a photographic and textually immersive installation that transports the viewer to centuries-old and prehistoric Native American mounds.

BY JULIE GARISTO

PHOTOS BY DANIEL VEINTIMILLASEPT. 5, 2018

Learn more when Suzanne Williamson and John Capouya visit the museum for a free free talk on Sept. 9, 2 p.m., “Envisioning Florida’s Sacred Landscapes through a Collaboration of Words and Images.”

As Floridians, whether natives or transplants, we learn to appreciate the intricacies of our landscape and human history — from the ancient aquifers and forests to native and invasive plants (yes, coconut palm tree, we’re talking to you) to the Native American tribes who lived and thrived here before European colonists displaced them and imposed their cultural and architectural influences.

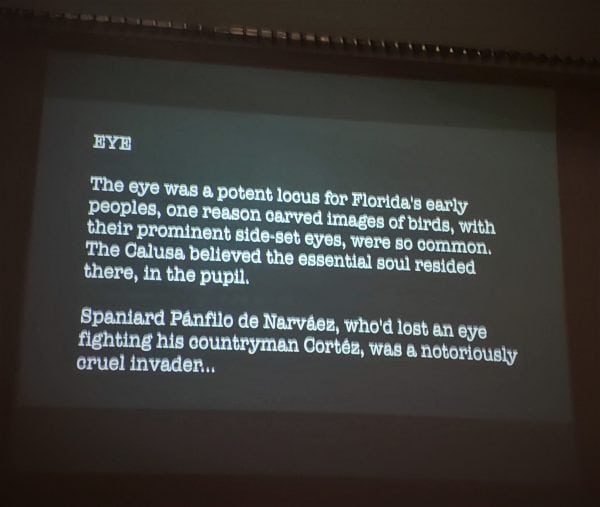

We appreciate a past that goes deep, revealed in the stories of Tocobaga, Timucua and other tribes who lived here long before the Spanish conquistadors laid claim to La Florida five centuries ago.

This month, you can take a road trip to the pre-developed Sunshine State, by way of the meticulously appointed and extensive Appleton Museum in Ocala, to see Suzanne Williamson and John Capouya’s installation Shadow and Reflection: Visions of Florida’s Sacred Landscapes.

The husband-wife-created exhibit, on display through Sept. 30, provides a breathtakingly atmospheric and narrative travelogue to Florida’s past, through words and images. Its impact has as much to do with what we learn as what it invites the viewer to imagine.

* * *

Sadly, much of Florida’s early history has been buried, and in many cases paved over or leveled. Locally, the civilizations of Manasota, Weedon Island, Safety Harbor and other ancient villages in Tampa Bay have long disappeared, but when you visit these sites, you might perceive a ghostly aura, an air of mystery whispering in the breezes that whooshes through veil-like moss and ruffles saw palmettos. We imagine the families of Timucua villagers; the men who wore their hair long with a topknot, the women in deerskin and woven cloth, and families who lived in their own homes though they gathered with others daily in the community to cook a potluck in a central location.

These sacred landscapes are underfoot almost everywhere we go. Much of downtown St. Petersburg, for instance, was built over sacred sites. “Anyone driving around the streets of downtown St. Petersburg should realize they are driving on top of historic mounds,” says Jim Schnur, president of the Pinellas County Historical Society, in the environmental publication Bay Soundings. “Below the surface of the streets around (USF St. Pete) Bayboro campus, Roser Park, Coquina Key, the shells from these mounds were crushed and used as pavement liner.”

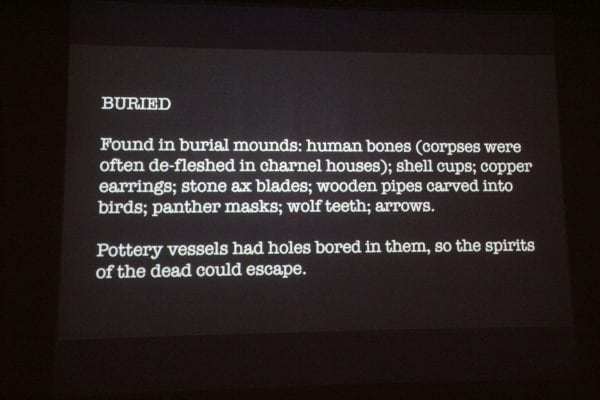

Though there are a few burial mounds — the spooky sites of campfire stories and horror movies like Poltergeist — most of Florida’s mounds are repositories of sacred artifacts and other items.

To capture the sites’ history artistically — to retell their stories sites and convey their special mystery through both images and words requires an attention to detail and imaginative approach, an endeavor accomplished creatively and masterfully by husband-and-wife team Suzanne Williamson and John Capouya.

Williamson, an award-winning photographer and former photo editor for ARTNews Magazine, began capturing the mystique of Native American mounds before leaving New York to live full-time in Florida.

“I was first introduced to ‘Indian mounds’ as they are often called, by a photographer friend, who had photographed along the Mississippi River,” Williamson explained. “She showed me a photo of a patch of wavy earth that could not have been naturally created. I asked what it was and she casually said they were ‘Indian mounds’ — didn’t I know about them?'”

Despite Williamson’s history and anthropology studies, this early history remained unknown to her up until that point, when she says she began to study it “in earnest.”

“This has been a major photographic interest in my life — bringing the presence and absence of history back for our appreciation,” she shares.

Her first trips to photograph mounds were to Ohio, where a major civilization named the Hopewell, built ceremonial and burial mounds in patterns sometimes connected to each other. “I have photographed the famous Serpent Mound in Ohio, Watson Brake, the oldest mound complex in North America and Monk’s Mound in Cahokia, Illinois. These incredible places were created at different times by different groups of First Peoples.”

In the Southeast U.S., near water resources, shell and sand were used to create mounds, Williamson says. “Most mounds have very specific layers of earth, shell or sand. They are not middens (heaps of stuff). They were built a basketful and layer at a time. There were many more, and we feel what remains is very precious to our world.”

Suzanne and John visited significant sites throughout Florida, which they include in their exhibition at the Appleton. The couple captured in photographs and words the stories of mounds at Sacred Lands in Pinellas County, Crystal River Archaeological Park in Citrus County, and The Calusa Heritage Trail in Lee County.

“Florida mounds are from different time periods that were part of or influenced by the other mound-building cultures in the eastern US.,” Williamson adds.

* * *

When the intrepid photographer first started making her landscape pictures of Florida’s Native American heritage sites, her husband, Capouya — author of Florida Soul and journalism professor at the University of Tampa — confesses that he really wasn’t that interested at first.

“In my journalism and nonfiction, I tell stories about people, not uninhabited sites, and I definitely didn’t want to drive long distances to see them — while standing outside in the Florida heat,” he says.

His initial reason for going was security. “Suzanne was heading into some remote areas alone,” he explains. “So I went, stood off to the side while she strode around and shot the mound from seemingly every angle.”

In time, though, he realized the history hidden in Florida’s mounds of earth and shell and sand have stories to tell –“they’re embedded there,” Capouya emphasizes — and that by doing some research, including talking to archaeologists who worked those sites, he could come to understand more about the past and the people who built them. And later he would construct his own narratives based on what he learned.

“But it wasn’t just fact-finding,” he clarifies. “I think the mounds got to me. As Suzanne and I visited these places, from Tallahassee to Lake Okeechobee, I began to see there was something special about them, even now, hundreds or thousands of years after the original peoples created them. These sites must have been chosen for reasons, and standing there, with Suzanne’s input, I started to feel both appreciation and a kind of awe.”

In one of the vignettes he wrote for the show, Capouya quotes a Native American archaeologist who told him that, to him, some of these places are “dead as a hammer,” but that “others are alive, alright.”

“I’m sure I didn’t feel what he felt but there was — there is — something,” Capouya says.

The Sacred Landscapes installation’s projected passages in a Courier-like typeface by Capouya — who also happens to be a mentor in the UT MFA Creative Writing Low Residency program that I attend — offer an intriguing variety of narrative approaches, from third-person descriptions to scripted dialogues. He also poses thought-provoking questions.

I emailed my first-semester Creative Non-Fiction mentor to ask how he arrived at these different approaches to the text. Capoya’s response:

“I definitely wanted to take many different approaches to these short pieces–I call them vignettes–if only to give the reader variety. There are 20 of them and I didn’t want them to be the same, in form or technique.

Just as important though, I had many different kinds of experiences, and reactions to them, while I was creating my work. Talking to a UF archaeology professor on the phone was quite different from standing next to a 30-foot mound amid almost total silence. Reading up on Native cultures (in books written by Westerners) is quite different from interviewing the ceremonial chief of the Muscogee Nation.

So, as a sort of guide and stand-in for the reader–or the viewer, since my words are projected on the walls of the Appleton Museum — I wanted them to experience what I had, including random thoughts, including about art; strong and at times wrong impressions of the mounds; attempts to relate the cultures that built these places to our own culture; and the like. (I also got some very great feedback from Helen Wallace, the poet laureate of St. Pete, a real lyrical writer.)

Example: At one point I realized I was feeling sorry for the Spanish invaders, who were even more ignorant than me and completely ill-equipped to deal with Florida. “That’s counter-intuitive,” I thought. “And that’s good!” So I wrote one piece about their suffering, which was real, though of course I did not ignore the savagery they inflicted on the peoples they encountered.

So the vignettes are deliberately impressionistic and, taken together, kind of a hodgepodge. But I’ll claim it or own it. As people who arrive or find themselves at unintended places often insist: I meant to do that.”

Using photographs printed on transparent fabric as well as metal and paper, Williamson first presented her photographs of mound sites throughout Pinellas County and statewide with her husband’s creative nonfiction vignettes at the Morean Arts Center in 2011.

At the Appleton, Capouya’s passages are presented on opposing walls at the center of the I-shaped installation with benches provided to relax and take in the narratives.

* * *

I asked Williamson to share her influences and how she was able to create such an ephemeral mood with her photography and her influences going into the project.

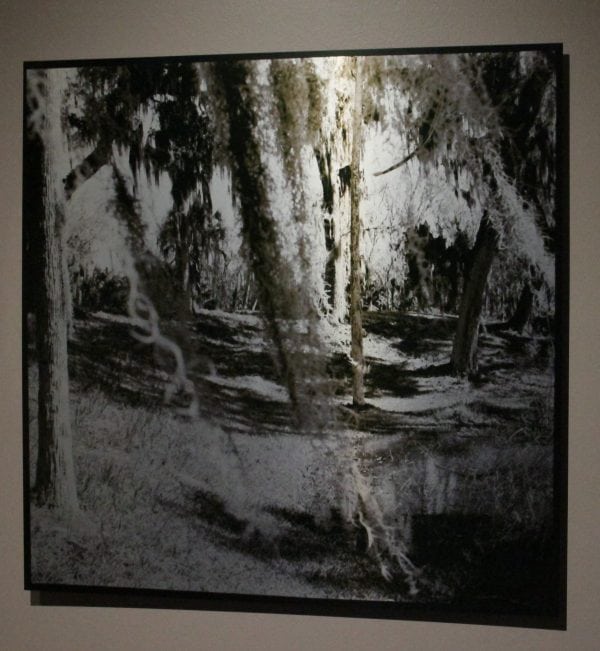

“My work in this series is inspired by nineteenth century expeditionary photographers, such as John Beasley Greene in Egypt and Désiré Charnay in Mexico, who photographed sacred monuments of the world with their own unique styles and processes. These artists understood how to visualize a historic place through time. I photograph using vintage cameras from the 1920s and 1950s, and black and white film. The lenses of these cameras allow me to pull my pictures in and out of focus, drawing the viewer into the space of these ancient settlements and monuments.

Working in the landscape, I look for ways to delineate depth and imply movement through space in a photograph. A photographer chooses their tools to achieve their ends, and is then guided and changed by their tools. My cameras allow me to shoot very close to a subject and still record the space beyond as more than background. Later in life I discovered that these images mimic my actual eyesight. I think that’s true for many artists.

My vintage cameras don’t have zoom lenses, so I am required to survey my subject and walk around to find my point of view. To me this is the heart of working outdoors — entering a world that I want to explore and share. I choose different times of day and types of weather to make images in natural light rather than try to override the conditions I find. The bright light and deep shadows in Florida are extreme — I respect them when I find them.

I feel a kinship with other contemporary landscape photographers whose work addresses issues of time and history.”

Shadow and Reflection: Visions of Florida’s Sacred Landscapes offers an intimate glimpse into what two married artists can create together. It’s a must-see for anyone seeking inspiration for a partnership collaboration or to drink in Florida’s ancient history. Each artist shines on his or her own and works harmoniously with the other — just as you do in any solid marriage. We’re also left curious about the couple’s future endeavors — both as individuals and as collaborators.