Humor and Darkness | Jake Troyli Talks Community and Inclusion

By SARAH TELESCA | Oct. 1, 2018

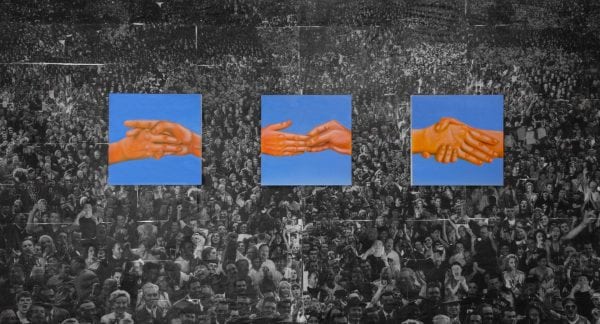

After being away from his home city of St. Pete for undergrad, painter Jake Troyli is happy to be back. His most recent show, “Awkward Handshake” at Tempus Projects, recently closed after being extended an extra week, meaning he’s already back in the studio working on new pieces. Currently rounding out his final year of his master’s degree at USF, his classically-rendered but culturally contemporary paintings explore exploitation, tradition, and long-held systems of oppression. Creative Pinellas talked with Troyli about using humor as a way to let the viewer in, Florida as a community, and his favorite contemporary painters.

Do you think it’s important to encase serious/dark subject matter in humor?

In my practice it is important because as an artist, you’re always looking for a way to hook the viewer; a way in. I see humor, for me, as that window of accessibility. I think what it can do is it can kind of break down some of those walls that we have up when we’re looking at a piece of work. That, I think, allows for a much more engaging interaction or experience, especially when talking about things that are serious, like race, or commodification of culture. Using humor I think is interesting because it creates an unexpected reaction. The viewer isn’t expecting to be laughing, or, once they’ve found it humorous they’re not expecting to uncover darkness. I think it’s possible to make the viewer feel a little bit guilty about laughing at some of these things. I think that that’s really interesting, putting your viewer in an uncomfortable position, and forcing them to re-examine their initial reaction.

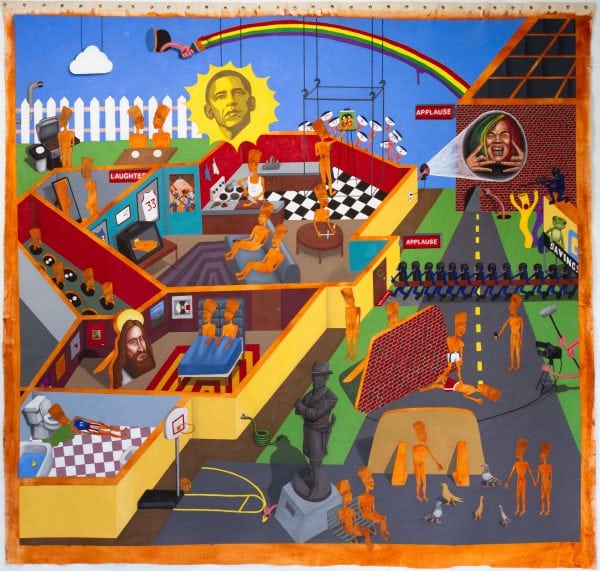

I think about race and the commodification of culture, how race works and the systems that are in place today — thinking of the proliferation of the systems that continue those ideas of division. That’s kind of at the base of everything I do. I like to think about what part we all play in these systems Whether we’re the spectacle or the spectator—what role, what part do we play? I also think about how I implicate my audience. I think that’s the trick — we’re all so quick to deny involvement. How do you turn that lens? How do you coerce an unsuspecting viewer in to acceptance of their role? Hopefully that can spark a new conversation. That’s why the work needs to be open — your subjective read of it allows for an objective view of the work, which then allows you to be fully be implicated, which allows you to actually see your own position in these systems.

What prompted the shift from devils to self as the subject of your work?

The devils were pre-grad school, so I think that period was just starting to build a language, starting to find a way that I wanted to express visual history.

First, I was making paintings of people whose images I had sourced from mug shots, so I was using them and placing them in these really classical portrait scenarios, and then I started to worry about that — I was like — am I exploiting someone else? Because I was sourcing these images from mug shots, it was like a double exploitation. I felt a little bit of guilt when I thought about it, so I was decided I was going to turn the lens back on myself. Once I did that, I realized that there was so much more room to really be expressive, because, shit—I can say anything I want about myself. I can absolutely push that to the limit. It was mostly inspired by my desire to have more freedom with the form, because I can take more liberties with my own form than with anyone else’s.

A lot of your work is very large scale. What’s the significance of your working so large?

I think a lot about how a painting can be immersive. These paintings use a voyeuristic viewpoint, an almost isometric perspective, so it’s like looking at an area with the top chopped off, like you’re playing a game of Sims. I think that for these paintings it’s necessary for the scale to be so large, because when you stand in front of it, it really becomes enveloping. When you’re right in front of a painting it becomes this encompassing thing.

In the show I had recently at Tempus Projects [“Awkward Handshake”] I lined two of the walls with this collaged crowd that I had made which I blew up and wheat pasted onto the wall, and then the huge paintings are straight ahead. Since the space is small and intimate, it really creates this immersive area where the works can bounce off of each other and play these visual games, enhancing the content of the other works. I don’t exclusively work large-scale, but I really like it for its ability to be immersive and for its ability to make the viewer feel a part of the scenario.

What artists are you currently into?

JT: My favorite artist, my hero artist, is Kerry James Marshall. With Kerry James Marshall there’s this conversation about the black figure in history of painting. That’s super interesting to me. So when I paint myself in the classical motifs, I think about what it means to be a black artist, and what does it mean to paint a black artist into this narrative that’s been non-inclusive? To be so attached to a tradition that’s not necessarily been attached to me, or my figure?

It’s funny to think about—how do you make a painting that’s aware of its own position as a painting? At the end of the day it is a painting, it is an object, but it’s also a statement, and I like to walk that line. I also like Kehinde Wiley and Kara Walker, I do like artists that sort of bend the rules, artists that will take an image and walk between representation and abstraction, so I like Dana Schutz, and Barnaby Furnas. My taste in art runs the gamut, but I like artists who assert the figure, who take the figure and think about its place in the work and think about its place in the context of the painting, so artists who think about themselves in the greater canon, I think that’s really interesting. And these artists are all, of course, working in the figurative tradition, which a lot of contradiction. I think its interesting to keep yourself on your toes, navigating those contradictions and really figuring out your place and the place of your work.

How does Florida work for you, as an artist? How does your community influence your work?

I love the USF community. I’m from St Pete, I did my undergraduate in South Carolina, and I ended up graduating from a school in Tennessee—I was on a basketball scholarship, so you go wherever the offer takes you. I’m really refreshed to have found the USF community, because it is small, but everyone is really helpful and supportive. Working with Tracy [Midulla] at Tempus [Projects], working with Cunsthaus, and Quaid, it feels like there is a lot of opportunity for contemporary artists, and it feels like there are a lot of spaces where ideas are going to be proliferated and given exposure. It feels really good.

I think that at the same time, that’s it. The USF community and these spaces are kind of where it ends in terms of the contemporary art sphere — it’s relatively small. You want to make this work, you want it to be seen and you want to have these conversations that start to come from it, and you do that as much as you can, but its still a small community.

But, I think the USF community has been amazing — and still is. I’m in my third year and we have this really tight bond. I’m a huge fan — I think there are positives and negatives of having a small community, but its 100 percent beneficial and necessary, really.

What are you working on?

I’m in the studio again working on some smaller things and seeing how they pan out — there’s always this letdown after a show, like coming off a high.

Right now it’s just this flow of work. I think through working, so as long as I’m working on a painting, I’ll be conjuring up new works and new ideas. I’m currently doing some small paintings of highway patrolmen and city police officers, but I’m painting them in this classical motif. They’re in contemporary police wear, but they’ll be in, like, Italian hills. I plan to do three of those. I’m doing another large painting of myself, sort of referencing David and Napoleon. I have things happening in the studio; there’s always this point where things start to feel electric and things start to generate.